Upper Saratown (Stokes County)

Upper Saratown (31SK1) is a site that actually has two primary occupations. The first occurred during the Early Saratown Phase (A.D. 1450-1620); while this has the same site number, this village occupation is called the Hairston site. The second phase of village life occurred during the Late Saratown Phase, from A.D. 1670-1710. This article is focused on the Late Saratown Phase; to find out more about the Early Saratown Phase, head over to the Hairston page.

History of Excavations

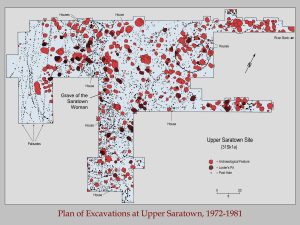

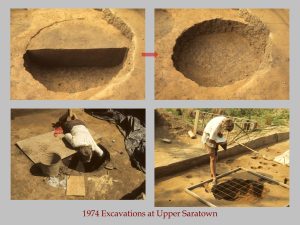

The first excavations at Upper Saratown began in 1972 and continued until August of 1981. The investigation happened as a response to extensive looting that occurred in the mid-1960s. UNC archaeologists Bennie Keel and Keith Egloff visited the site in January of 1972, interrupting a looter in progress and salvaging the partially disturbed burial. The historic Saratown burials were known for particularly rich grave offerings, resulting in the site being a prime location for looters to visit. Excavations began the next summer in 1972 and continued every summer through August 1981. This was all done in an effort to properly document as much of the village as possible before it was entirely destroyed by looters. The site itself covers 2.5 acres, containing an extensive midden. Additionally, six human burials and 40 features were recovered, including storage pits, earth ovens, shallow basins, and hearths.

Research Questions

With its occupation during the early historic period in the North Carolina Piedmont, Upper Saratown is very interesting for what it can tell us about Native peoples’ interactions and experiences with colonialism. Upper Saratown was a palisaded village that probably contained about 200 to 250 people living together in circular houses. The most characteristic features at the site were large, deep, almost perfectly circular storage pits, generally over three feet in diameter and just as deep. These storage pits contained rich deposits of food remains and other domestic refuse. Large roasting pits (“earth ovens”) were also uncovered, usually located around the edge of the village near the palisade. These were probably used to prepare the large amounts of food needed for ritual celebrations.

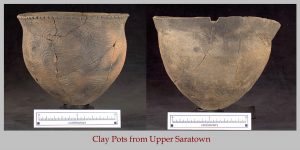

The artifacts found during excavations show that there were a lot of continuations from the Early to Late Saratown phases. Pottery continues to be what archaeologists call the Oldtown series, with similar construction and decoration styles. Similarly for subsistence, we see a balance between domesticated plants like corn, beans, squash, gourds, and peaches, along with other wild resources. And despite higher numbers of deaths, burial practices continue as well. Graves continue to be placed around and within houses and were primarily shaft-and-chamber pits, where people were buried with large amounts of European trade goods, especially glass beads and copper pieces. This was to change during the end of the Late Saratown phase, when we see a separate cemetery area at the William Kluttz site.

One of the most interesting parts of the Upper Saratown site has to do with the trade goods found at it. As Virginia traders began making more regular trips into the “back country,” the numbers of trade goods at sites like Upper Saratown increase dramatically. However, while thousands of glass beads, copper bells, and other ornaments were recovered from Upper Saratown, there were very few tools and weapons. This contrasts starkly with Occaneechi Town, where guns, iron knives, and hatchets were found in large quantities along with beads and trinkets. This suggests that the Sara were receiving their trade goods through middlemen like the Occaneechi. By controlling the flow of goods to more remote groups like the Sara, the Occaneechi were able to keep and control access to firearms and weapons, only supplying decorative goods to other groups. The downside of the increased flow of goods during the Late Saratown phase is an increase in European diseases; according to Ward and Davis (1991), “…many of the excavated villages appear more like cemeteries than habitation sites.”

Sources

Ward, Trawick H., and R. P. Stephen Davis, Jr.

1998 • Time Before History: The Archaeology of North Carolina. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.