By Modern Tribe

Many people don’t realize that North Carolina has the largest population of American Indians east of the Mississippi River. As of the 2000 U.S. Census, there were almost 100,000 American Indians in the state; this includes one federally recognized tribe, seven state recognized tribes, and four Urban Indian organizations.

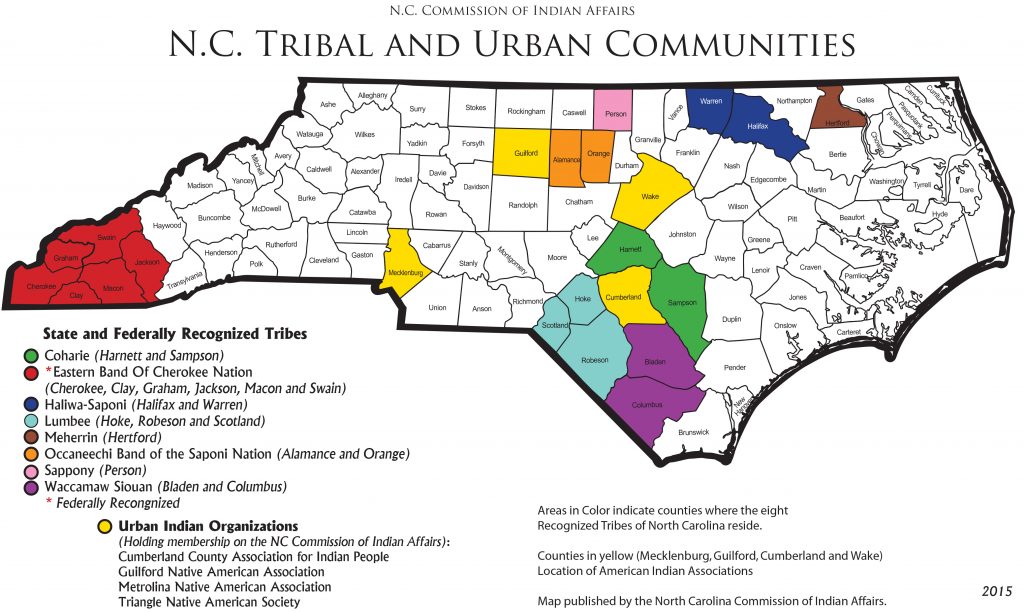

While most of this website details contributions that American Indians made in the past, it is critically important to recognize the contributions American Indians make to the present and future. Below we have information about each of the state and federally recognized tribes and provide links to tribal websites where possible. If you scroll down further, you can also see a map showing the locations of modern tribes within the state of North Carolina, as well areas covered by Urban Indian organizations.

North Carolina Tribes

The present population of the Coharie Indian Tribe is located predominantly in southeast NC in the counties of Sampson and Harnett. Coharie tribal members descended from the aboriginal tribe of the Neusiok Indians. Historical movements, caused by Inter-tribal as well as White/Indian colonial hostilities, moved the Coharie to their present location sometime between 1729 and 1746. The contemporary Coharie community consists of four settlements: Holly Grove, New Bethel, Shiloh, & Antioch. The modern day Coharie Intra-Tribal Council, Inc. is the outgrowth of an election of tribal members in 1975 to unite the Coharie organizations from Harnett & Sampson Counties into a single body to provide effective leadership, avoid duplication & seek projects that could benefit all Coharies regardless of county lines.

More than a thousand years ago, Cherokee life took on the patterns that persisted through the eighteenth century. European explorers and settlers found a flourishing nation that dominated the southern Appalachians. The Cherokees controlled some 140,000 square miles throughout eight present-day southern states. Villages governed themselves democratically, with all adults gathering to discuss matters of import in each town’s council house. Each village had a peace chief, war chief, and priest. Men hunted and fished; women gathered wild food and cultivated ‘the three sisters’ corn, beans, and squash cleverly inter-planting them to minimize the need for staking and weeding. Nearly 200 years of broken treaties had reduced the Cherokee empire to a small territory, and Andrew Jackson began to insist that all southeastern Indians be moved west of the Mississippi. The Cherokees in Western North Carolina today descend from those who were able to hold on to land they owned, those who hid in the hills, defying removal, and others who returned, many on foot. Gradually and with great effort, they have created a vibrant society a sovereign nation of 100 square miles where people in touch with their past and alive to the present preserve timeless ways and wisdom.

Haliwa-Saponi tribal members are direct descendents of the Saponi, Tuscarora, Tutelo, and Nansemond Indians, and smaller Eastern Siouan-speaking tribes. For about three decades, the remaining members of these tribes lived at Fort Christianna, which was established to support trade and to Christianize and educate tribal members. In the mid-1700s, a fairly large body of Saponi left Fort Christianna and settled in Old Granville County in North Carolina. In the mid-1700s, the Nansemond migrated to North Carolina from Virginia and bought several large tracts of land that make up the modern day Haliwa-Saponi community. This area, known as the Meadows, encompasses most of southwestern Halifax County and southeastern Warren County (from which the Haliwa-Saponi get their name. These ancestors of the Haliwa-Saponi lived a semi-traditional life of farming, hunting, and fishing. Those who did not own their land lived with relatives or served as sharecroppers for white planters, some traveling as far as 30 miles from home to work and live.The Haliwa-Saponi Tribe was recognized by the state of North Carolina in 1965.

The Lumbee Tribe is the largest tribe east of the Mississippi River, the ninth largest tribe in the United States, and the largest non-reservation tribe in the United States. A Cheraw community was first observed on Drowning Creek (Lumber River) in present day Robeson County in 1724. In 1835, the N.C. State Constitution was amended to disenfranchise Indians (along with Blacks) and rescind citizenship rights. In 1885, the N.C. General Assembly recognized the Indians of Robeson County as Croatan and established a separate school system for Indians. In 1887, the state established a Croatan Indian Normal School, with this institution growing into a college, known as the University of North Carolina at Pembroke (UNCP). In 1911, the N.C. General Assembly changed the name of the tribe to “Indians of Robeson County”. In 1933, a bill was introduced in congress to recognize the Indians of Robeson County as “Cheraw”. In 1952, the Indian leaders held a community referendum to get approval of tribal members to change the name to “Lumbee Tribe” and in 1953, the N.C. General Assembly changed the name of Indians of Robeson County to “Lumbee”. The Lumbee hold no treaty with the federal government. However, the Congress of the United States in 1956 passed the Lumbee Act officially recognizing the Native American Indians of Robeson and adjoining counties as the Lumbee Indians of North Carolina. This bill, however, contained language that made Lumbee ineligible for financial support and program services administered by the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA).

Meherrin refer to themselves as Kauwets’a:ka, pronounced (gau went ch-AAga), “People of the Water.” Meherrin are an Iroquois Nation that share allegiance, culture, traditions, and language with the Tuscarora, Nottoway, Cherokee, and other Haudenosaunee Nations. The first written account of the “Meherrin” people began on August 29, 1650 when an English merchant named Sir Edward Bland led an expedition from Fort Henry (Petersburg, VA) to the Meherrin village, Cowonchahawkon (Emporia, VA). In 1705, the VA Assembly assigned a circular tract of land to be set aside for the Meherrin making it the first Reservation (Maharineck) in NC. The Meherrin became tributaries of NC on March 4, 1729, and an act of NC Assembly enlarged the Reservation. The Meherrin have always defended their “Turtle Island” (United States) and have fought in every major war. In 1757, Meherrin, Tuscarora, Nottoway, and Sappony enlisted at the request of Col. Washington in the Colonial Army in Williamsburg, VA to fight the French. Fifteen Meherrin fought in the American Revolutionary War and 39 Meherrin enlisted in the Army at Wilmington, NC on the same day during the Civil War. Today, under the leadership of Chief Wayne Brown and seven elected Council members, the Meherrin tribe was placed on Active Status with the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The annual Powwow is held the first weekend on Oct. on Hwy 11, between Ahoskie and Murfreesboro, NC.

The Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation is located in Alamance and Orange Counties, in the old “Texas” Community. This is where the tribe is developing its 25 acres of former tobacco land into a tribal center facility which will include a reconstructed 1701 Occaneechi Village, 1880’s Log Farm, as well as office space, community meeting area, pow-wow grounds, and tribal museum. The Occaneechi descend from several small Siouan speaking tribes who were living in the Piedmont of North Carolina and Virginia when the first European explorers arrived in the 1600’s. John Lawson met their ancestors in 1701 when he visited the area that is now modern-day Hillsborough, North Carolina, in a small village on the banks of the Eno River. A decade later, the Occaneechi would unite with the Saponi, Tutelo, and other smaller tribes at Fort Christanna, Virginia, forming a federation that went under the name Saponi. By the late 1700’s, the ancestors of the modern Occaneechi had returned to what is now Alamance and Orange Counties, where they lived as small farmers and craftsmen.

The Sappony have made the gently rolling highlands of the Piedmont their home for countless generations. Today, the Tribe’s 850 members call the area known as the High Plains their home. High Plains is located along the borderline that separates North Carolina and Virginia. In the early 1700’s, when the Sappony children were attending school at Fort Christanna and the Tribe was guarding the frontier for the colonies, they were also helping to mark the North Carolina-Virginia borderline. The same borderline runs through the High Plains settlement. As a result, part of High Plains is located in the northeastern section of Person County in North Carolina and part is located in the southeastern section of Halifax County in Virginia. The first Indian school in the High Plains community began as one room in their Baptist church in 1878. In 1911, after receiving legislative recognition from the state of North Carolina, the Sappony built and partially funded the High Plains Indian School. Virginia recognition followed in 1913 which allowed the Indians living on the Virginia side of High Plains to attend the same school. The Indian school was closed in 1962 with the advent of assimilation.

The present population of the Waccamaw Siouan Indian Tribe is located predominantly in southeast North Carolina in the counties of Bladen and Columbus, in the communities of St. James, Buckhead and Council. The first written mention of the Waccamaw-Siouan Tribe appeared in the historical records of 1712 when a special effort was made to persuade them, along with the Cape Fear Indians, to join James Moore’s expedition against the Tuscarora. The Waccon Indians, the Siouan tribe that Lawson placed a few miles to the south of the lower or hostile Tuscarora, ceased to exist by the name Waccon but that they moved southward as a group and became the Waccamaw Indians. Tribal names were often changed or altered, especially by the whites in their spellings, and the Waccamaw appeared first in historical records at about the same time the Waccon name disappeared. The Waccamaw, then known as the Waccommassus, were located one hundred miles northeast of Charleston, South Carolina. In 1749, a war broke out between the Waccamaw and the State of South Carolina. Twenty-nine years later, in May 1778, provisions were made by the Council of South Carolina to render them protection. It is believed that after the Waccamaw and South Carolina War, the Waccamaw sought refuge in the swamplands of North Carolina.

Urban Indian Organizations

The mission of Cumberland County Association for Indian People (CCAIP) is to enhance self-determination and self-sufficiency as it relates to the socio-economic development, legal, and political well-being of the Indian People of Cumberland County. Fostering healthier choices is one of many areas the CCAIP Board works on to improve the lives of its members. We support the planning and delivering of services by utilizing local, state, and national networking resources in the following areas: (1) Education, (2) Native arts and crafts, (3) Cultural enrichment, (4) Job referrals services, (5) Employment and training, (6) Economic development, and (7) Housing and health needs.

In September 1975, in response to a nearly 100 percent dropout rate of American Indian students from Guilford County’s three public high schools, a small group of parents began working with members of local Lutheran churches to create a 501(c)(3) non-profit association. Today, as the oldest American Indian urban association in NC and one of the oldest in the U.S., the Guilford Native American Association (GNAA) has progressed from a single program focus of educational advocacy to become a multi-service organization. The GNAA board has ten members who are elected by the American Indian community at the organization’s annual meeting. Board members serve three-year staggered terms with either two or four new members elected each year.

The Metrolina Native American Association (MNAA) was organized in the early 1970s by a group of American Indian families who met in each other’s homes with the goal of assisting native people in the area to stay connected. The MNAA Board of Directors has seven members, elected at large, who serve three-year, staggered terms. The MNAA Board is ethnically and educationally diverse. MNAA has 175 registered members in the 10-county service area of which about one-third are active. Seventy percent of MNAA members are Lumbee but nearly all of the NC tribes are represented, as well as tribes such as the Ute and Chippewa-Winnebago.

In 1983, a group of residents in the Triangle (Durham, Raleigh, and Chapel Hill, N.C.) assembled to organize a social network for American Indians living in the area. The TNAS Executive Board is made up of the current officers (president, vice-president, secretary, and treasurer) and emeritus presidents. There are currently eight board members. Officers are elected at the annual meeting held on the first Monday in October (if there is a quorum of regular members as stated in the by-laws) and serve for one year. TNAS membership meetings are held on the first Monday of each month at the Wade-Edwards Learning Lab in Raleigh. The society gained a seat on the North Carolina Commission of Indian Affairs (NCCIA) Board in March 2000. TNAS currently does not have a physical office or paid staff.

One Response to “By Modern Tribe”

Imagining Duke’s Campus in 1000 AD - Duke University Libraries Blogs

[…] for each nation, pointing to newspapers, councils and leaders, as well as a map of the 8 tribal nations recognized by the State of North Carolina. There are four urban Indian organizations, including […]