Appalachian Summit

The Appalachian Summit in North Carolina presented native peoples with an environment very different from the Piedmont and Coastal Plain. The rugged topography has some of the highest peaks east of the Rocky Mountains. Higher elevations range between 4,000 and 6,000 feet and are characterized by gaps, ridges, knobs, and knolls. Lower elevations consist of steep slopes, often narrow valleys, and floodplains. The North Carolina Appalachian Summit has been referred to as a “sprawling confusion of mountain ranges.” This terrain had a dramatic effect on how the region was used – or not used- by Native Americans.

The Appalachian Summit in North Carolina presented native peoples with an environment very different from the Piedmont and Coastal Plain. The rugged topography has some of the highest peaks east of the Rocky Mountains. Higher elevations range between 4,000 and 6,000 feet and are characterized by gaps, ridges, knobs, and knolls. Lower elevations consist of steep slopes, often narrow valleys, and floodplains. The North Carolina Appalachian Summit has been referred to as a “sprawling confusion of mountain ranges.” This terrain had a dramatic effect on how the region was used – or not used- by Native Americans.

The Paleoindian is the time of the earliest generally accepted arrival of people in the southeastern United States – about 16,000 years ago, or 14,000 B.C. Although earlier migrations of people into the New World have been hypothesized, currently there is no firm evidence of people anywhere on the continental United States prior to 14,000 B.C.

Our level of understanding of the Paleoindian period across the state is highly uneven, due to both the history of North Carolina archaeology and environmental and geological factors.

Paleoindian Chronology in North Carolina

Archaeologists working in the Southeast use radiocarbon dating and differences in spear point forms and frequencies to tell time during the Paleoindian. Questions regarding settlement and subsistence can be addressed by studying the frequencies and distribution of the various types of spear points.

Paleoindian in the Southeast is divided into Early, Middle, and Late periods. Spear points of the Early Paleoindian period (14,000 – 9,000 B.C.) are large, fluted lanceolates, very similar to the classic Clovis points of the West. What we know about the earliest inhabitants of North Carolina is based almost entirely on surface finds of these points. Concentrations of Early Paleoindian points have been noted in the Tennessee, Cumberland, and Ohio River valleys, as well as western South Carolina, southern Virginia, and the northern Piedmont of North Carolina.

In the Middle Paleoindian period (9000 – 8500 B.C.) the number of spear points increases considerably and regional variability in spear point forms emerge. The Cumberland, Suwanee, and Simpson point types are thought to be typical of this Middle period. One thing all have in common is a narrowing, or “waisting,” at the base.

The Late Paleoindian period (8500 – 7900 B.C.) shows increased population growth. Dalton points are the diagnostic Late Paleoindian point type. By the end of the Paleoindian, Holocene climatic conditions prevailed and the basic hunting and gathering lifeway that persisted for the next 5000 years was set.

Paleoindian Settlement and Subsistence in North Carolina

Paleoindian settlers in the Southeast found a rapidly changing landscape. Current evidence suggests that many of extinctions of Late Pleistocene megafauna – including the horse, mastodon, and mammoth – were complete by 8500 B.C.

East of the Mississippi River almost no Paleoindian tools have been found with these animals. Environmental differences between the Eastern and Western parts of the continent may have necessitated very different adaptions. By the Middle Paleoindian period, if not earlier, the subsistence pattern was probably very similar to that of the Early Archaic period.

Most southeastern Paleoindian sites where more than a single point has been found are related to stone-quarrying activities. This pattern reflects a generalized foraging where groups rarely engaged in subsistence activities that produced recognizable traces in the archaeological record.

Paleoindian in the North Carolina Mountains

Only a few Paleoindians sites have been found in the North Carolina mountains, and no buried, stratified sites have been found. As a result, little can be said about subsistence and settlement patterns in the Appalachian Summit area during Paleoindian times. Boreal forests comprised of spruce and fir probably persisted in the higher elevations of the southern Appalachian Summit throughout Paleoindian times. Now-extinct Pleistocene animals probably persisted later in the mountains than they did in other regions.

Close Paleoindian

The Archaic (8000 – 1000 B.C.) covers over half of the timespan people have lived in North Carolina. This vast time has been explored by finding well-preserved deposits in rock-shelters and stratified, deeply-buried open sites in alluvial floodplains. The Archaic is generally thought of as a period dominated by nomadic, relatively small bands pursuing a hunting and gathering way of life, but there is evidence that some Archaic people settled into larger and more permanent sites relatively early.

The Archaic in the Appalachian Summit

Very little Archaic period research has been conducted in the Appalachian Summit region. Some Late Archaic sites have been excavated (see below), but much of the reconstruction of Archaic chronology, settlement, and subsistence in the mountains leans heavily on research in neighboring southeastern Tennessee.

Early Archaic

No deeply buried, undisturbed Early Archaic components have been excavated in the North Carolina mountains. Early Archaic materials in southeastern Tennessee differ from those recovered at the Hardaway site in North Carolina. Other Early Archaic projectile point traditions, particularly side-notched and bifurcated base points, are present in the mountains.Most Early Archaic sites located in high, upland areas produced a wide range of tools reflecting hunting, butchering, hide working, and woodworking. Early Archaic groups established only temporary camps in the rugged Appalachian Summit region, while maintaining more permanent base camps in the Ridge and Valley province of east Tennessee.At these base camps in Tennessee, large quantities of charred acorns and hickory nuts were found, as well as prepared clay hearths. Impressions of basketry and textiles provide the earliest well-dated evidence of weaving in eastern North America.

Middle Archaic

The Middle Archaic period in the North Carolina mountains is indicated by the occurrence of Stanly Stemmed, Morrow Mountain Stemmed, and Guilford Lanceolate spear points (much the same as the Middle Archaic in the Piedmont).Most Middle Archaic settlements in the mountains consist of dispersed camps situated on a variety of valley and upland landforms. This dispersed settlement pattern may reflect the slightly warmer and drier conditions of the Altithermal climate.In contrast to Early Archaic tools, most Middle Archaic specimens were made from locally available rock. Stone atlatl weights provide the first concrete evidence for the use of the atlatl. Stone netsinkers suggest the increasing importance of fishing.

Late Archaic

The Warren Wilson site in Buncombe County and the Tuckasegee site in Jackson County contained Archaic strata. Numerous rock hearths were present at Warren Wilson, and fragments of steatite bowls.

Riverine resources were no doubt important in the Late Archaic. Hunting and fishing were supplemented by harvesting large numbers of acorns and hickory nuts. Squash and gourds were cultivated as early as 3000 B.C. and towards the end of the Late Archaic period sunflower, maygrass, and chenepodium were well on the way to being domesticated.

Late Archaic Savanna River Stemmed and Otarre Stemmed spear points at the Warren Wilson site dated from about 3000 to 1500 B.C.

Close Archaic

Three interrelated innovations marked the end of the Archaic and the beginning of the Woodland: pottery-making, semi-sedentary villages, and horticulture. All had their origins in the Archaic but became the norm during Woodland times. In North Carolina, the Woodland is divided into Early, Middle, and Late periods. Along the coast and through much of the Piedmont, the Late Woodland continues until Contact, while in the Appalachian Summit and in the Southern Piedmont, Mississippian and Mississippian-influenced societies developed after A.D. 1000.

While Piedmont Woodland cultures were characterized by continuity and gradual internal change, the Woodland of the North Carolina mountains was a time of increasing cultural diversity stimulated by ideas from outside the region. Much of what is known about the Early and Middle Woodland periods in the Appalachian Summit is the result of research in eastern Tennessee.

Beginning in the 1960s, the University of North Carolina’s Cherokee project established the chronological and stylistic markers of the Woodland and research by the University of Tennessee at Knoxville filled in details of settlement, subsistence, and overall cultural change and adaptation.

Early Woodland – The Swannanoa Phase (1000 – 300 B.C.)

Early Woodland ceramics similar to the Piedmont Badin series are found in the Appalachian Summit. The Swannanoa pottery series has thick vessel walls (from 7 mm. to 22 mm.) with cordmarked and fabric-impressed surfaces. Check-stamped, simple stamped, and plain surfaces were added later in the phase. A few steatite vessel sherds suggest continuity with the preceding Late Archaic period.

Stylistically, Swannanoa pottery is similar to Kellog ceramics of North Georgia, Watts Bar pottery of eastern Tennessee, and Vinette wares of eastern New York state.

The Swannanoa phase is characterized by small, stemmed projectile points called Swannanoa Stemmed, Plott Stemmed, and Gypsy points. These represent the last gasp of the stemmed-point tradition that began at the close of the Late Archaic period.

Like other varieties of Early Woodland stemmed points, the Swannanoa phase points also were found stratigraphically associated with a large triangular point type named “Transylvania Triangular.”

Although several kinds of Swannanoa phase features were found at Warren Wilson site, large hearth areas composed of clusters of fire-broken rock were most common. These stand in marked contrast to the relatively small, circular pit hearths of the preceding Late Archaic period. No cultigens or seed plants have yet been found in the small sample of subsistence remains known for Swannanoa phase. Rather, arboreal nut crops show continuity with Archaic economic pursuits.

Middle Woodland (300 B.C. – A.D. 800)

Current evidence suggests that Middle Woodland connections can be seen in areas outside the Appalachian Summit region. Two distinct phases of Middle Woodland occupation have been recognized: the Pigeon and Connestee phases.

Pigeon Phase (300 B.C. – A.D. 200)

Early in the Middle Woodland period ceramic connections are seen to the south, where carved wooden paddles were first used to stamp the surfaces of pottery vessels.

Connestee Phase (A.D. 200 – 800)

In spite of a clear developmental relationship with the Pigeon phase, Connestee phase is distinctive. Exotic artifacts show connections with other Middle Woodland groups and indicate participation in the Hopewell interaction network. Later in Connestee phase, southern influences from the Swift Creek area of southern and central Georgia continue to be felt after the Hopewell climax.

Middle Woodland pottery reflects a dramatic break with the cordmarked and fabric impressed ceramics of the Swannanoa phase. Vessel forms and surface treatments show continued change throughout the Woodland Period.

Large triangular points began during the Swannanoa phase and appear to be associated with the introduction of the bow and arrow. During the Middle Woodland period small sidenotched and triangular projectile points are found.

Late Woodland (A.D. 800 – 1100)

Cultural dynamics and stylistic markers of the Late Woodland period in the Appalachian Summit region are poorly understood. One excavated site that appears to have been occupied during this time is the Cane Creek site in Mitchell County.

The Cane Creek site had a remarkably homogenous ceramic assemblage with plain, smoothed, or brushed surfaces, and frequently notched vessel rims. None of the tetrapodal vessel supports of the preceding phases were found. Cane Creek’s well-preserved assemblage of bone tools and mortuary pattern are similar to Late Woodland cultures throughout the Southeast between A.D. 800 and 1200.

The cultural uniformity of Cane Creek site only heightens the seeming disparity between Woodland cultures and the Mississippian-influenced cultures that appeared abruptly after A.D. 1200.

Close Woodland

The South Appalachian Mississippian tradition, with its complicated-stamped ceramics, stockaded villages, substructure mounds, and agricultural economy appeared abruptly after A.D. 1000 and continued until European contact. The emergence of Mississippian culture in the Appalachian Summit is abrupt and a hypothesis of extended, in situ cultural evolution is tenuous.

Pisgah Phase (A.D. 1000 – 1450)

Pisgah phase people’s dependence on agriculture and their construction of elevated platform mounds upon which temples or chiefly residences were built mirror important changes in sociopolitical organization. Extensive excavations at two sites, Warren Wilson and Garden Creek, make the Pisgah phase one of the best understood cultural complexes in the Appalachian Summit.

Lamar Culture and the Qualla Phase (After A.D. 1350)

Qualla phase is a manifestation of the widespread Lamar culture found across the northern half of Georgia and Alabama, most of South Carolina, and eastern Tennessee. Qualla phase in the Appalachian Summit falls within the Middle Lamar and Late Lamar periods, continuing until the time of sustained European contacts with Historic period Cherokees.

The Eastern Fringe of the Appalachian Summit (After A.D. 1350 to Historic Period Cherokee

The chronological and cultural relationships between Pisgah, and Qualla and Lamar phases are further addressed by sites in the Catawba River valley, where temporal overlap forces a re-examination of the traditional view of a Pisgah-to-Qualla developmental sequence.

At the conclusion of the University of North Carolina’s Cherokee project in the 1970’s, the culture history of the Appalachian Summit during the Woodland and Mississippian seemed clear. A straightforward sequence of development from Early Woodland Swannanoa phase to the Qualla phase and the Historic period Cherokees, had been outlined. New information from surrounding regions has made it clear that the ideas that once seemed so clear and straightforward will continue to require re-examination.

Close Mississippian

The time of contact between Indians living in North Carolina and Europeans arriving from Spain and England varied considerably across the state. The expedition of Hernando de Soto passed through western North Carolina in the spring of 1540. Pardo’s expeditions into the same areas came less than 30 years later. The first English attempts at settlement in northeastern North Carolina came about 20 years after that, starting in 1584. But it was not until after about 1650, when English explorers, traders, and settlers came from Tidewater Virginia, that North Carolina’s Indians felt the brunt of the European presence on their land.

Accordingly, the beginnings of these arrivals do not necessarily herald the beginnings of significant changes in the histories of North Carolina’s tribes. Overall, however, this was a time of sweeping and often devastating change.

Contact in the Appalachian Summit

Both the Appalachian foothills (the upper Catwaba valley) and the Appalachian summit in western North Carolina were visited early on by the de Soto and Pardo expeditions in the middle 1500s. The Berry site, which was occupied during this time, appears to have been the town the Spanish described as Joara, when it was visited by the de Soto expedition in 1540 and by the Juan Pardo expedition from 1567-68.

After the Spanish expeditions, the Cherokee in and near the Appalachian Summit were insulated from European contact for a century. Some degree of trading and raiding were carried on with the Spanish settlements to the southeast. Then, in the 1670s, trade relations were set up with Virginia traders. In the early 18th-century English traders began to push west through the Blue Ridge mountains and along the upper Piedmont of South Carolina and Georgia. Here they found the Cherokee, a populous people in a widely scattered collection of towns. The Late Qualla phase represents Cherokee culture during this time period.

The Late Qualla phase (A.D. 1700 – 1838)

The Cherokee remain somewhat isolated until the close of the Tuscaroa War in 1713. By the 1730s European diseases had spread to the Cherokee country. A smallpox epidemic in 1738-39 destroyed half of the tribe. During the mid-century the Cherokee were increasingly drawn into European rivalries and English, and later American, expeditions into the heart of Cherokee territory destroyed towns and killed many Cherokees. In these wars the Cherokee lost much of the political and military power they had previously possessed. Beginning with the Treaty of Hopewell in 1785 and culminating with the Removal of 1838 each treaty cost them more and more of their mountain homeland.

The pottery of the Late Qualla phase reflects the stability and conservatism that mark the beginning of this phase. No drastic changes demarcate the Late Qualla ceramics from pottery of the Middle Qualla phase.

Pottery from the Townson site, which dates to the second half of the Late Qualla phase, is similar to earlier Qualla pottery, but decorations are bolder in form and more crudely executed.

The Cherokee probably built both circular and rectangular houses. Throughout the Southeast, circular houses were used mainly as winter dwellings and rectangular houses were summer dwellings. After about 1776 rectangular houses became the dominant form.

House form at Townson also differed greatly from earlier rectangular Qualla houses. Instead of individual posts set in the ground, the walls of the house at Townson were formed by split rails laid one atop another and anchored to four corner posts. Cracks were chinked with clay. The house probably looked much like a contemporary Euro-American log cabin. However, inside the house was the traditional central puddled-clay hearth found in earlier Cherokee houses. A very similar Cherokee house was described in a letter relating the experiences of a soldier who participated in the 1776 attacks on Cherokee towns.

As house types changed during the Late Qualla phase, so did village configurations. Townson site consists of houses scattered along a terrace, whereas Middle Qualla villages were compact and usually stockaded. This process of population dispersion intensified as acculturation and pressures to change increased . By the time the Cherokee were forcefully removed in 1838 most families lived in isolated farmsteads and small hamlets.

Some Cherokee habitations had large numbers of artifacts, including non-native commercially manufactured items, while others contained mostly native-made items. These differences probably reflect varying degrees of acculturation and participation in the colonial market economy. Subsistence practices also changed. The Cherokees readily adopted Old World animals, and most families kept horses, cows, pigs, and chickens.

Although the population became more dispersed, town houses continued to be used and rebuilt at the same locations long after the main villages had been abandoned. The religious and ceremonial realms of Cherokee culture retained their traditional form and practice.

North Carolina today is the home of the largest Native American population east of the Mississippi River. The robust cultural diversity seen in the archaeological record of the last 12,000 years survives today in the tribal traditions of North Carolina’s native peoples.

Close Historic

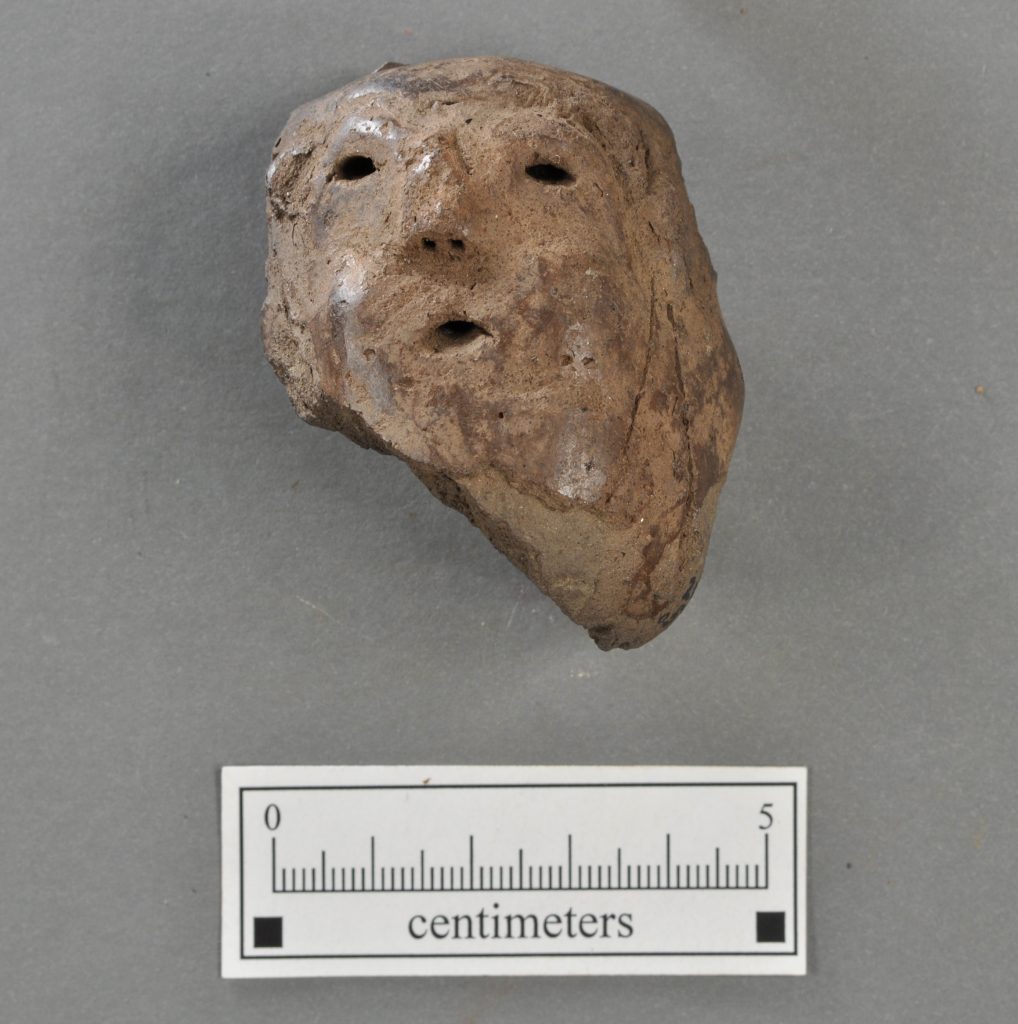

- Clay pipe fragment from the Coweeta Creek site in Macon Co., NC

- Shell gorget from the Warren Wilson site in Buncombe Co., NC

- Shell gorget from the Warren Wilson site in Buncombe Co., NC

- Columella shell beads from the Warren Wilson site in Buncombe Co., NC

- Conch shell from the Warren Wilson site in Buncombe Co., NC

- Clay animal effigy from the Warren Wilson site in Buncombe Co., NC

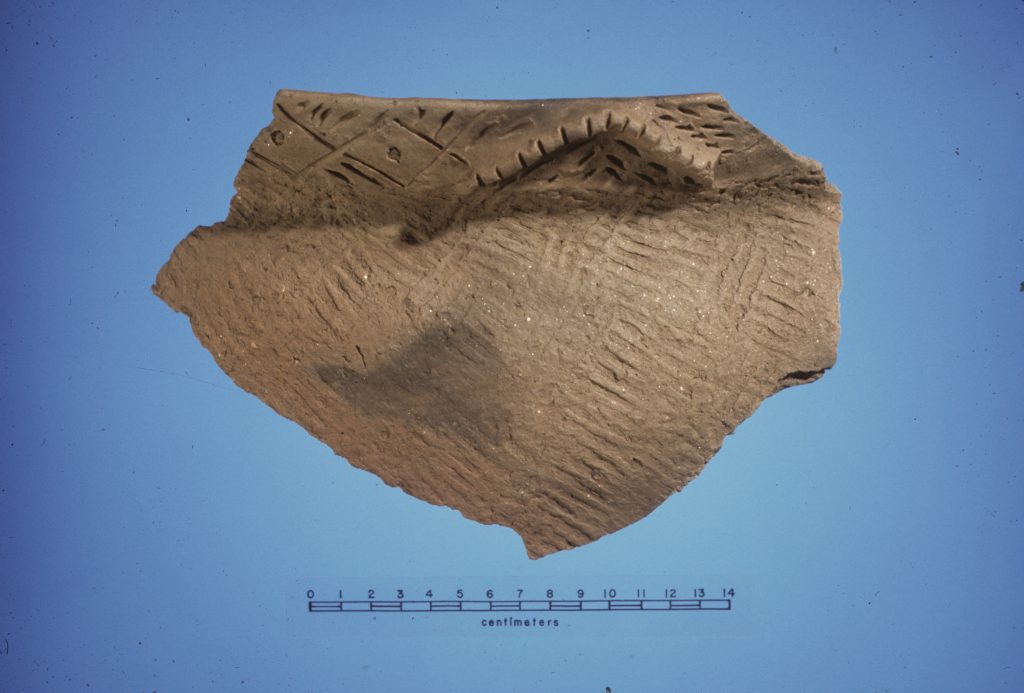

- Pisgah Complicated Stamped jar fragment from the Warren Wilson site in Buncombe Co., NC

- Pisgah Check Stamped jar fragment from the Warren Wilson site in Buncombe Co., NC

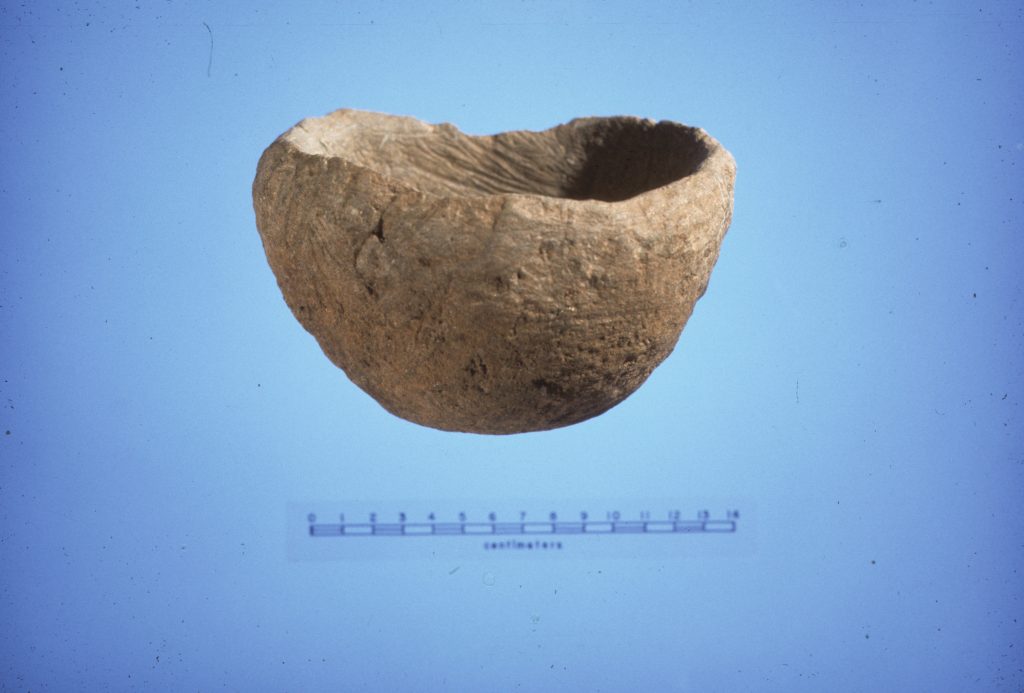

- Soapstone pot from the Warren Wilson site in Buncombe Co., NC

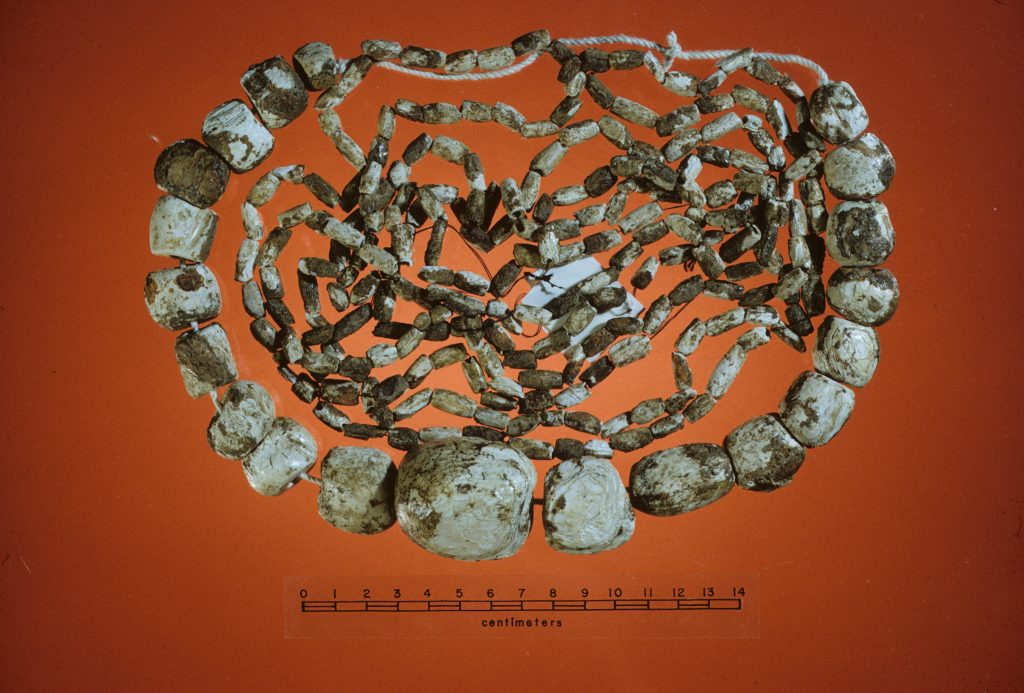

- Shell beads and gorget from the Warren Wilson site in Buncombe Co., NC

- Shell beads from the Warren Wilson site in Buncombe Co., NC

- Duck effigy pipe from Cherokee Co., NC