Welcome

We all feel connected to our personal history, how it has shaped the person we are today and will condition who we become tomorrow. Our society, too, has been formed by its history. For hundreds of generations, people have lived in the very places we do, have prospered, failed, and endured. The past offers us a unique perspective on who we are, personally and culturally.

North Carolina’s past is rich almost beyond belief. Archaeological and historical sites offer the opportunity to travel in time. We can explore an old mining camp in our western mountains, walk through 18th-century Moravian streets in Old Salem, or contemplate the meanings of the drawings etched on Judaculla Rock by sure hands centuries ago. Take a walk in the fertile floodplains by rivers and note the chipped stone and broken pottery at your feet; it tells you that you are only the most recent visitor to a place that was visited by countless earlier people. In some places in North Carolina, you can stand at a site and take in a landscape little changed by centuries. You see what those who came before you saw and imagine another way of life. You become richer for knowing the human history of your home.

Studying the past gives us a rare chance to examine our place in time and forge links with the human continuum. Archaeologists also want to learn about the many cultural lifeways people have chosen and how these lifeways have changed over time. Anthropology, archaeology’s parent discipline, seeks to understand human behavior in a broad sense. Archaeology contributes to anthropological knowledge by studying behavior through the artifacts and other material evidence that people left behind.

Archaeologists study both ancient and recent historic periods. Archaeology is one way we have to study people who left no written records; in North Carolina, this includes almost 97 percent of the human occupation span—all of which comprises the history of Indian peoples who preceded the arrival of Europeans in the 1500s.

Until recently, much of what archaeologists had discovered was tucked in technical reports written mostly for other scholars. Committed to make the information more widely available, Vincas P. Steponaitis and Margo L. Price conceived the North Carolina Indian History Project in 1992. Based in the Research Laboratories of Archaeology (RLA) at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, this project is guided by the assumption that teachers in the state’s schools are one of the best ways to share what archaeologists have learned about Indian history. The project’s goal is to raise public awareness of this state’s long history of Indian settlement. One means of achieving that goal is to organize and give workshops for teachers that let them understand how archaeologists as scientists work and what archaeology can and can’t say about a people’s past.

Early on, we had to face the issue of how to present archaeological information to K-12 teachers. We realized that teachers had limited classroom time and that they had to fulfill very specific curriculum requirements. So we turned for help to another university unit: the Center for Mathematics and Science Education (CMSE), now the UNC Baccalaureate Education in Science and Teaching Program (UNC-BEST), a part of UNC’s School of Education. The staff at CMSE, experienced in organizing continuing education courses for teachers accredited by the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, became our partners. They helped chart and administer a pilot two-week teacher residency workshop funded by the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation. Dedicated to showing teachers how to teach science in innovative ways, the CMSE’s internal mission dovetailed with the RLA’s. Archaeology inherently fascinates students, luring them into the realms of hypothesis testing, classification, and other science processes at the same time it crosses multidisciplinary borders like social studies, history, geography, math, and art.

Preparing for the pilot workshop soon led us to another partner. Contacts through the Society for American Archaeology’s Public Education Committee led to the Bureau of Land Management’s (BLM’s) Cultural Heritage Education Program based in Colorado. In their own multi-agency effort, they had devised Project Archaeology, an archaeology-education program for teachers of grades 4 through 6 built on a Utah curriculum called Intrigue of the Past. Talking with the BLM staff, RLA and CMSE organizers found the BLM not only shared similar goals, but they had a jump start. Their Intrigue of the Past held a series of extensively tested and teacher-friendly lessons designed to draw on students’ interest in archaeology and simultaneously to enhance their skills in science, math, higher-order thinking and communication. Intrigue’s lessons also fostered a sense of responsibility for stewardship of irreplaceable archaeological sites.

The Intrigue curriculum was used in the North Carolina Indian History Project’s pilot workshop. Even though its text featured examples and illustrations drawn largely from archaeological research in the West, the approach to teaching archaeological processes, concepts, and ethics was generic. North Carolina archaeologists and instructors verbally substituted information relevant to North Carolina. Teachers applauded it. Yet they pointedly said they needed the verbal input in writing.

Today, the North Carolina Indian History Project is the child of the three partnerships and the experience of the pilot workshop. With BLM’s permission, the Project Archaeology curriculum has taken on a distinctively North Carolina look to become Intrigue of the Past: North Carolina’s First Peoples.

There is one caveat for those who wish to use this book of the lesson plans: it will never be finished. Over time, the guide will be modified as teachers, Native Americans, archaeologists, and other educators give feedback about what works, what doesn’t, and what else they would like.

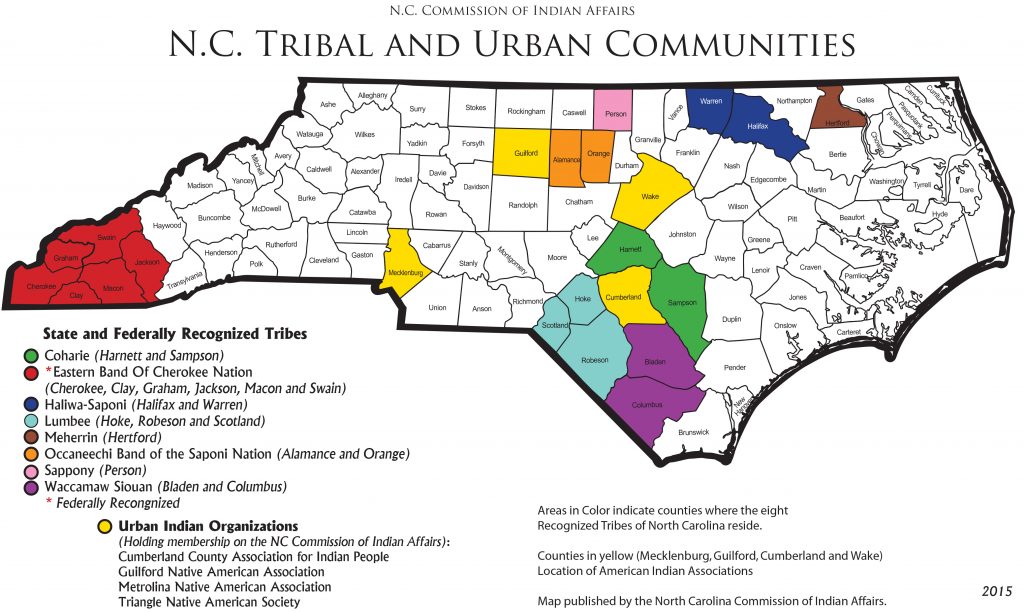

The living descendants of pre-Columbian people on this continent are the American Indians. According to the North Carolina Commission of Indian Affairs, more than 80,000 Indian people live in North Carolina today, representing 1.2 percent of the state’s population. In fact, North Carolina has the largest Indian population east of the Mississippi River. At least some Indian people reside in each of the North Carolina’s 100 counties, but about 80% of the state’s Indian population is concentrated in eleven counties: namely, Columbus, Cumberland, Guilford, Halifax, Hoke, Jackson, Mecklenburg, Robeson, Scotland, Swain, and Wake. About half of the state’s Indian people live in Robeson County, where they comprise 39 percent of the county’s population.

Seven tribes have state recognition: Coharie, Eastern Band of Cherokee, Haliwa-Saponi, Indians of Person County, Lumbee, Meherrin, and Waccamaw-Siouan. The Eastern Band of Cherokee also have Federal recognition. Other state recognized Native organizations include: Cumberland County Association for Indian People, Guilford Native American Association, Metrolina Native American Association, and Triangle Native American Society. Detailed information on North Carolina’s Indian peoples, both past and present, can be found in the readings compiled in Appendix A.

It is important to realize that teaching lessons in this guide is also teaching Indian peoples’ ethnic history. Teach it with sensitivity and respect, as you would the story of your own ancestral past. Also keep in mind that this guide represents the archaeological view of North Carolina’s Native American history, which is only one perspective. The scenario of the past as told by the things people left behind provides some information about their ancestors’ cultures—what people ate, what their homes were like, how their culture changed over time. However, archaeological methods cannot give information regarding their thoughts, beliefs, and hopes. Nor is it possible to dig up religion, medicinal knowledge, kinship reckoning, dances, festivals, calendar-keeping, recipes, child-rearing practices, or a multitude of other aspects of what it means to be human.

Indian people traditionally have their own ways to pass along details about their ancestors’ lifeways, handed down from generation to generation through stories, ritual, religion, teaching, and myth. They sometimes have a view of their history that differs from the archaeological perspective. It is important to realize that the Indian view and the archaeologist’s view are two different ways of looking at the past; neither one is inferior or superior to the other.

Archaeology makes inferences about the past based on a scientific analysis of material data. Scientific rules of evidence are applied. For some Indian people, a scientific view based on archaeological evidence is often not regarded as the most meaningful explanation of their cultural tradition.

Recently, there have been many examples of Indians and archaeologists learning about each other’s perspectives and the different kinds of information each group can provide. Most importantly, both Indian people and archaeologists agree that sites and artifacts should be protected and that cooperation in saving them is essential.

Certain issues, however, remain very sensitive, especially regarding human burials encountered by archaeologists as they excavate sites. Archaeologists sometimes have been insensitive to the spiritual and religious beliefs of Indian people, and unfortunate confrontations have occurred. Conversely, cooperation between archaeologists and Indian people in documenting information from burials or in recovering those in danger of destruction by development or natural forces demonstrates how positive the relationship between the two groups can be.

While it is important to be sensitive to Native American cultural considerations, don’t stereotype all Indian people as being closely connected to their traditional culture. Just as all European Americans do not relate to a European heritage, Indian people connect in varying degrees to their ancestral past. Also realize that there is no such thing as a single “Indian culture.” At the time of European contact, many different tribes lived in North Carolina, divided linguistically, geographically, and culturally.

Indian people today can be as diverse in their views of an issue as is American society in general. They can have a range of opinions and lifeways practiced within one tribe or organization, just as within any community.

There is a danger of conveying two erroneous concepts when studying the distant past. One is stereotyping pre-Columbian people either as primitive, backward, and warlike savages or, conversely, as noble savages living an idyllic life perfectly in tune with nature. The other misconception is that archaeologists are interested only in artifacts.

Both misconceptions can be remedied by emphasizing that archaeologists study people in all their cultural variation. Archaeologists come to understand them by studying the artifacts they left. These objects are important because they are messengers of ancient people’s culture. Stripped of context and viewed solely as mute things, artifacts are of little use in deciphering history.

Like people everywhere, pre-Columbian people exhibited an array of talents and personalities. Some were worriers, and some were light-hearted; there were born leaders and shy people, hard-workers and lazy folks. They faced conflict and war and benefited from cooperation and friendship.

As a group, pre-Columbian people possessed considerable skill and understanding of their world. Their knowledge enabled them to live successfully in environments that today seem inhospitable to us. Most of us would not survive a week in the wilds without the accompaniment of many pounds of modern technology. The natural world was the Indian’s pharmacy, grocery, clothing, and hardware store, supplying food and raw materials for all manner of things, from baskets to houses to medicine and clothing. Pre-Columbian people had a deep and special knowledge of their world, and this fact cannot be trivialized if we are to perceive them accurately.

It will become obvious after studying this guide how little we really understand about the people who lived in North Carolina millennia before us. The data archaeologists rely upon to tell us the story of their past is fragile and is disappearing at an alarming rate.

A theme to emphasize throughout this guide is the role every person can play in protecting archaeological sites so that the data will be available to help us fill in gaps in our knowledge. It is illegal to collect artifacts and to dig Indian sites or historic sites on federally or state-owned lands. Don’t encourage others to destroy the past by buying artifacts. Report violations you witness to law enforcement authorities or land-managing agencies, such as the U.S. Forest Service, the National Park Service, or the North Carolina Office of State Archaeology.

Everyone has the opportunity to touch the past and to access information gained by archaeological research. Sadly, however, that opportunity is disappearing in North Carolina. The number of sites that have not been disturbed or looted is dwindling at an alarming rate. Greed and ignorance rob us of our heritage and the chance to experience and connect with the past. For Indian people living in North Carolina today, archaeology is the only way they have to supplement the knowledge handed down by their elders through legends and oral histories. Sometimes, archaeology is the only echo of their ancestors’ voices.

An illegal and thriving market in antiquities supports the destruction of sites by looters in search of artifacts. Vandals dig up Indian villages and burials, ignorant or uncaring of the fact they are destroying information or desecrating places of spiritual and historical significance to Native Americans. Also, many people innocently collect a few projectile points, glass beads, or rusty horseshoes, not knowing they are walking away with the data archaeologists rely on to study the lifeways of past people.

State and federal laws protect sites on public lands, but law enforcement is only part of the solution to protecting our past. Education and teachers can influence whether the school children of today will know and experience North Carolina’s rich cultural legacy as the adults of tomorrow.

Education in archaeology serves three purposes. First, it promotes a sense of responsibility and stewardship of America’s cultural heritage. Secondly, archaeology is an innovative means to capture students’ attention while addressing many educational concerns in the classroom. This interest is perhaps the most attractive aspect of teaching with archaeology. Almost everyone seems to be curious about it—the intrigue of the past.

Archaeology is an integrative, interdisciplinary field. Archaeologists ask questions rooted in the social sciences and research those questions using scientific methods. This fusion of the social and physical sciences means that archaeology is an excellent way to teach students to think holistically, to integrate information from different topics. The study of archaeology can also address some of the concerns of educators today, such as scientific inquiry, problem solving, cooperative learning, and citizenship skills.

Intrigue of the Past: North Carolina’s First Peoples results from a marriage of the Bureau of Land Management’s Project Archaeology and the University of North Carolina’s Research Laboratories of Archaeology’s commitment to provide a program designed to share with and teach North Carolina students about our state’s rich and fascinating past. Equally important, the program emphasizes that the archaeological evidence of that past is fragile and threatened, and we all have a responsibility to see to its wise use.

Intrigue’s teaching materials include two main components. Activities form the foundation; they include information about the fundamental concepts, processes, and issues of archaeology. Essays in Chapter 3 give teacher-oriented, more detailed information about four periods in North Carolina’s ancient history as archaeologists have come to understand it. Ideally, the essays should be skimmed prior to starting Intrigue lessons with your students; they are written to give you better grounding for activities in the other four parts. Students can benefit from Chapter 3’s “Quick studies.” Appendixes include places to visit suitable for all ages and a bibliography of selected readings. Items suitable for young readers are specifically noted.

Intrigue presents an integrated means of teaching archaeology. Activities provide comprehensive understandings of concepts, issues, and insights in archaeology; information from the essays reinforce them through additional culture history. Designed with you, the educator, in mind, all activities are self-contained and use readily available materials that require little preparation to teach. Many of the activities help you teach required concepts and skills.

Intrigue of the Past: North Carolina’s First Peoples does not include guidance for undertaking time- and labor-intensive activities, such as mock digs and dioramas. While these activities can enliven the study of archaeology, they are best built on the basic ideas presented here and are not necessary for giving students a grounding in the science and issues of archaeology. Also, be aware that conducting a dig or collecting artifacts at a real site on public land without a federal or state permit is a violation of law. Be aware that digging on private lands without the guidance of professional archaeologists destroys valuable information that can never be replaced.

Ideally, you will be introduced to Intrigue teaching materials by attending a workshop. If this is not the case, you have only one piece of the complete program. Workshops provide a forum for experiencing the activities first hand, for asking questions and exchanging ideas with teachers and archaeologists, and for providing current information about archaeology in your area. Also, you can get information about networks in your area you may want to tap into, such as avocational archaeology clubs, speakers, newsletters, and ongoing fieldwork.

To find out about workshops, or to share suggestions or comments, you may contact the Research Laboratories of Archaeology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3120; telephone (919) 962-6574.

Intrigue’s teaching materials support many state curriculum requirements in the subjects of science, social studies, language arts, mathematics, and visual arts. Current teaching strategies—such as scientific inquiry, problem solving, values clarification, higher-level thinking skills, and teaching and learning styles—are woven into the lessons.

Teaching cooperative skills at all levels of thinking is important. Specific cooperative learning lessons have not been included. Rather, most of the lessons lend themselves to the cooperative learning process.

Instructors are encouraged throughout the guide to adapt the lessons according to teaching and learning styles, class size and age, time, subject, or any other considerations. Educators in scouting, outdoor education, youth groups, and after school programs will also find this material useful.

This book is organized into the five parts listed below.

- Chapter 1: Fundamental Concepts

- Chapter 2: The Process of Archaeology

- Chapter 3: North Carolina’s First Peoples

- Chapter 4: Shadows of People

- Chapter 5: Issues in Archaeology

These parts are followed by a set of appendixes.

The activities are flexible; many of the lessons can be taught individually, although Chapter 1 is a prerequisite to the rest of the guide and is to be taught as a whole. Chapters 1 and 2 are prerequisites for activities in Chapter 4. Chapter 5 activities are best taught after students have received a background in archaeological concepts and methods.

Intrigue can be used as a unit or as part of a year’s thematic study. Because there is no prescribed sequence, some information is repeated in several places.

Chapter 1: Fundamental Concepts

Activities in this part teach the fundamental concepts necessary for understanding archaeology: the importance of the past, culture, observation and inference, context, chronology, classification, and scientific inquiry. Teaching this part as a unit prior to other lessons will prepare students to more easily assimilate information from the rest of the guide. The lesson “It’s in the garbage,” is an activity in which students use each of the concepts they have covered in Chapter 1 to analyze and interpret archaeological evidence.

Chapter 2: The Process of Archaeology

This part is about the process of archaeology: finding, excavating, analyzing, and interpreting archaeological sites and data. The lessons build on the basic concepts presented in Chapter 1. If taught as a whole, this part will give students a broad understanding of the archaeological process, but the lessons are designed to be taught singly as well.

Chapter 3: North Carolina’s First Peoples

This part focuses on aspects of Native American lifeways during the time from 16,000 years ago until European contact, and it contains four substantive essays. The essays themselves are teacher-oriented, but they are also accompanied by “Quick studies,” which summarize key points about each cultural period and can be distributed as study aids for students. Use them to foster discussion about how lifeways differed across time, or how they compare to the way we live now. Each essay links to activities in Chapter 4.

Chapter 4: Shadows of People

While each is self-contained, Chapter 4’s lessons feature some aspect of life discussed in Chapter 3. All but one require grounding in concepts covered in Chapters 1 and 2. The exception is Chapter 4’s opening lesson “Shadows of North Carolina’s past.” It can be used prior to beginning lessons in Part 1. Use it as a hook to lead students into basic archaeological inquiry: How do we know what we know about the past? Or use it to launch into a comparative study of lifeways over time, based on Chapter 3’s “Quick studies.”

Chapter 5: Issues in Archaeology

Many archaeological issues today revolve around how sites and artifacts are to be conserved and used. This part presents lessons about these issues and gives students a chance to examine their own beliefs and values about the past. Students need background knowledge to thoughtfully form values. Therefore, lessons in this part should be taught only after students have a broad understanding of archaeology. It is very important to give students the opportunity to draw together their knowledge and feelings about the past. Values clarification brings closure to the learning process and promotes personal responsibility. A lesson on “Archaeology as a career” is also included.

Appendixes

The appendixes present supplementary material that teachers will find useful in both presenting the lessons and extending them. Appendix A contains a list of titles for further reading, including books geared to young readers. Appendix B compiles information on archaeological sites in North Carolina that are open to the public and that can be visited on school or family trips.

Each lesson is designed to teach one or two archaeological concepts. Lessons are organized using the following outline of headings.

- Objectives: highlights the content, process, and product of the lesson

- Materials: lists all materials needed

- Vocabulary: list of key words, defined

- Background: information for the teacher

- Setting the stage: an activity to hook students’ interest

- Procedure: step by step process to teach the lesson

- Closure: an activity to conclude the lesson

- Evaluation: suggestions for assessing student learning

- Extension: some lessons contain additional activities

- Links: a reference to other lessons that address similar concepts

- Sources: sources from which background materials are drawn

A key (at the head of each lesson) lists subjects addressed, skills learned, strategies used to teach skills and concepts, duration, and class size.

Activity sheets for students to complete are included in many lessons. Some lessons include masters that can be used as teaching aids. Both activity sheets and masters are reproducible as transparencies or handouts. The activities are easy to prepare and all materials are included or readily available.

When Intrigue of the Past was first published in 2001, the lesson plans within it were categorized based on the teaching standards within North Carolina. While the specifics of teaching standards have changed over the years, for consistency we have stayed with the original divisions of lessons by Subjects, Skills, and Strategies. Based on what you are teaching, this allows you to mix and match the lessons that are most appropriate for your classroom. However, in all cases we do recommend that you teach all of Chapter 1: Fundamental Concepts so that students understand the fundamental concepts of archaeology.

We have organized the tabs to the left to provide easy access the lesson plans in different groupings:

Intrigue of the Past provides materials from the entire book, in the same order you would encounter them in the book.

Subject Areas provides a breakdown of lessons grouped by the subjects they address.

Skills provides a breakdown of lessons grouped according to skills that area learned through the lessons.

Strategies provides a breakdown of lessons grouped according to the strategies that are used to teach the skills and concepts.

Highlights represents Lessons that teachers have found particularly useful within their classrooms.

Vocabulary reproduces Appendix 1 from the book, and provides a location to look up words that you or your students may be unfamiliar with.

Links provides a number of external resources, including addition archaeological lesson plans.