The Graham Memorial Site

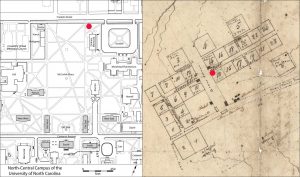

The Graham Memorial site is located on old Chapel Hill Lot 13, at the southeast corner of Franklin Street and Grand Avenue (now McCorkle Place). This two-acre parcel was sold by the University trustees at auction on October 12, 1793, and throughout the nineteenth century and first two decades of the twentieth century, a tavern house which later served as a hotel and boarding house stood here at the north edge of the University of North Carolina campus. Built in 1796 or 1797, it was one of the first commercial structures in Chapel Hill and during its heyday was known as the Eagle Hotel. It passed through numerous owners, name changes, and many phases of additions and renovations, but throughout its lifetime served primarily as a place of lodging for visitors to the campus and university students.

Ann Segur “Nancy” Hilliard (1807–1873) was the well-regarded proprietress of the Eagle Hotel during the 1830s and 1840s. In reflecting upon her tenure at the hotel, Kemp Battle remarked:

“There was one Hotel, the Eagle, presided over by the eagle-eyed old maid, Miss Nancy Hilliard, who had all the traveling custom and most of that of the University. Her table was bountiful and the food well cooked, and the wonder was how receipts could balance expenses. She was accustomed to say that she lost on the students, but the travelers and the rich harvests at Commencements more than supplied the deficiency. How much her uncollected dues from students unable or unwilling to pay, amount to, will never be known, but they were very large” (History of the University of North Carolina, Volume 1, by Kemp P. Battle, 1907).

While she was proprietress, Hilliard expanded the hotel, adding a two-story house to the east side to accommodate President James K. Polk upon his return to his alma mater in 1847 to receive an honorary doctorate. She also built a much larger annex to the rear of the hotel that stood at the present site of Graham Memorial Building. These expansions provided a residence for almost 100 students during the years leading up to the Civil War. In 1852 Hilliard sold the hotel and built a house, nicknamed the “Crystal Palace,” next door on Franklin Street. The site of this structure now lies beneath the Morehead Planetarium parking lot and sundial.

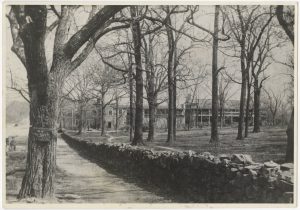

In the years following the war, the hotel remained a center of social life for the university and town, but it never reclaimed the degree of prosperity it enjoyed during earlier decades. The photograph of the hotel at right is one of only a few that have survived from the late nineteenth century. It was taken about 1892 from the front of the Roberson Hotel on Franklin Street (where Battle Hall now stands) and shows the University Inn and Annex (formerly the Eagle Hotel) across McCorkle Place. The original structure for the 1790s Tavern House and early Eagle Hotel is at left. Shortly after this photograph was taken, the hotel was sold and extensive renovations were made to transform the property into a profitable resort hotel. The old tavern building was torn down and replaced with a large, Queen Anne-style structure with a tall turret and an expansive porch. The annex which had been built at the rear of the building, as well as additions to the east, were left intact.

This business venture failed, and in 1908 the Chapel Hill Hotel and University Inn Annex, as the hotel was now known, was acquired by the university to be used as a dormitory. During the following decade, the facility was poorly maintained and in 1921 it caught fire and was completely destroyed. After its destruction, the site of the hotel remained largely untouched, except for construction in 1931 of Graham Memorial Building immediately to the south.

The Graham Memorial site was the first site on campus to be investigated by UNC archaeologists. During the 1993–1994 academic year, excavations were conducted as an archaeological field school in conjunction with the University’s bicentennial celebration. In addition to revealing physical evidence of Chapel Hill’s earliest years and obtaining important information about early student life, the project provided an opportunity to train students in methods of archaeological field research and to showcase how archaeologists investigate an historic site.

After establishing a grid of 5-ft-by-5-ft units across the suspected site area, initial excavations focused upon an area at the south edge of the site near Graham Memorial Building. Systematic auger testing, undertaken prior to the start of excavations, had revealed deeply stratified layers of soil containing artifacts and other debris from the building along the brick walkway adjacent to McCorkle Place. Sanborn insurance maps from the early 1900s also indicated that the north end of the hotel’s large annex, constructed on the south side of the hotel sometime during the 1830s and 1840s, stood at this location. It also was suspected that this area might contain discarded “back yard” refuse from the early era of the Tavern House.

In the photographs at right, field school students are excavating this “back yard” area located just south of where the Tavern House and early Eagle Hotel stood. The topsoil was quite thin over much of this area and contained few artifacts that could be attributed to the earlier tavern and hotel; however, two significant archaeological features were revealed in the first two units that were dug.

The first unit that the students excavated revealed the top of the shallow foundation trench from the annex, less than a foot beneath the ground surface. This archaeological feature, aligned north-south, can be seen in the top photo of the expanded excavation.

Just west of this excavation unit, toward McCorkle Place, a second unit contained much deeper archaeological deposits which extended almost three feet below the surface. These deposits were subsequently sampled in several additional units and are clearly visible at the edge of the excavation in the bottom photo. They represent two distinct features: a drainage ditch adjacent to the east wall of the annex that gradually filled in with refuse during the mid-1800s, and an earlier, deeper ditch to the west that appears to have filled in with refuse during the earliest years of the tavern and hotel. Five soil zones were identified within the older ditch and excavated separately. In the uppermost zone, students found artifacts of modern campus life, including aluminum pull tabs, a beer bottle cap, and fragments of phonograph records. Deeper deposits produced fragments of broken whiteware dishes and discarded glassware, wood charcoal, and other building debris that most likely were deposited when fire destroyed the structure in 1921. At the bottom of the excavation unit, the students found items that dated to the earliest years of the university, and which can be attributed to the Tavern House and the early Eagle Hotel. These included an English gunflint, a clay marble, a lead button, fragments of English white-clay tobacco pipes, and numerous pearlware sherds.

For the remainder of the fall semester, the field school students excavated within a 25-ft-by-30-ft area to expose more of the foundation trench and the much deeper deposits of late eighteenth and nineteenth-century refuse that accumulated along the west side of the hotel, next to McCorkle Place.

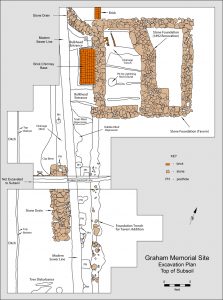

During spring semester, excavations focused on locating the Tavern House and Eagle Hotel foundations. The first trace of the tavern to be uncovered was the brick base of the west chimney, buried less than half a foot below the ground surface. As the topsoil was removed just east of the chimney, students and archaeologists encountered several large stones at the top of a massive, dry-laid stone foundation which supported an 18-ft-by-18-ft building and enclosed a 15-ft-by-15-ft cellar. Oriented along Franklin Street, the cellar extended only about 2-3 feet below the present ground surface and likely was a half, or English, basement with small above-grade windows letting light into the cellar. The two-foot width of the stone foundation suggested that it supported a two-story structure, a conclusion that is consistent with late nineteenth-century photographs showing the original tavern building. By the 1840s this structure had doubled in size to 36 ft by 18 ft.

The top of the cellar was filled with debris from the early 1890s when the original tavern and hotel was demolished. In particular, this upper deposit contained much of the brick from the chimneys that stood at each end of the structure. Beneath the debris were three cellar floors, still largely undisturbed and each separated by sand that had been intentionally deposited to help alleviate moisture problems. Several broken plates and bowls, as well as a few coins, buttons, a brass keg tap, and other small artifacts, lay on these floors where they were broken or lost (view 3D models below). A stone foundation that crosses the cellar was added in the 1890s to support the west wall of the newly constructed Chapel Hill Hotel, and it was laid atop these floors.

Quite unexpectedly, the archaeological excavation at the Graham Memorial site produced substantial information about how the hotel’s owners dealt with problems of moisture and drainage. Being dug into stiff piedmont clay, the building’s cellar acted as a “catch-basin,” partially filling with water when it rained. On two separate occasions, the cellar floor was raised by depositing a half-foot thick layer of clean river sand. Although this tactic probably worked temporarily, it did not solve the problem since the water had nowhere to go. Following the apparent failure of the second layer of sand to keep the floor dry, a much more radical step was taken. A shallow drainage ditch was cut diagonally across the sand floor to the northwest corner, where it fed a newly constructed, stone-lined drain. This drain connected to a ditch about six feet west of the tavern which directed water to the edge of Franklin Street. A similar stone drain along this ditch also was found just southwest of the tavern, beneath an entryway to the rear addition. These drainage features can be seen at right in the excavation plan for the Graham Memorial site.

3D Models of Artifacts

Clay smoking pipe from the Eagle Hotel cellar entrance

Brass keg tap from the Eagle Hotel cellar floor

Blue transfer-printed plate from the Eagle Hotel cellar floor

Whiteware plate from the Eagle Hotel cellar floor

Stoneware butter pot from the drainage ditch adjacent to the Eagle Hotel

US Large Cent (1816-1819) from the Eagle Hotel annex

Blue transfer-printed wash basin fragment from the Eagle Hotel annex

Contributor

R. P. Stephen Davis, Jr. (Research Laboratories of Archaeology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill)

* Image courtesy of the Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

**Images courtesy of the North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

***Images courtesy of the Research Laboratories of Archaeology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Sources

Davis, R. P. Stephen, Jr.

2015 • The Hidden Campus: Archaeological Glimpses of UNC in the Nineteenth Century. Gladys Hall Coates University History Lecture, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, April 14, 2015.

Davis, R. P. Stephen, Jr., Patricia M. Samford, and Elizabeth A. Jones

2010 • The Eagle and the Poor House: Archaeological Investigations on the University of North Carolina Campus. In Beneath the Ivory Tower: The Archaeology of Academia, edited by Russell Skowronek and Kenneth Lewis, pp. 141-163. University Press of Florida.