The Pettigrew Site

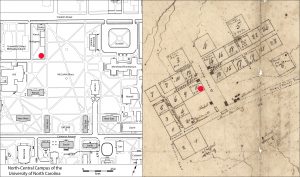

The Pettigrew site is located just north of Pettigrew Building and was investigated in 1997 prior to the construction of Hyde Hall, home to UNC’s Institute for the Arts and Humanities. The site was originally part of Lot 11, a two-acre town lot on the west side of McCorkle Place that was sold at auction by the university’s trustees in 1793. The lot fronted on Franklin Street and was originally purchased by George Johnston. By the time the university re-acquired the last part of the sub-divided tract in 1929, it had changed ownership some two dozen times. When first surveyed for archaeological remains, it was believed that the site was largely associated with the Phi Delta Theta fraternity house which stood there from the beginning of the twentieth century until the early 1930s. However, since this area was the back yard of a residence built on Franklin Street during the late 1790s and was also the back lot of the Roberson (later Central) Hotel which stood at the site of Battle, Vance, and Pettigrew buildings in the late 1800s, earlier archaeological remains were expected as well. Archaeological investigations demonstrated that it also was the site of a substantial, privately owned dormitory known as the Poor House. This building was constructed during the second quarter of the nineteenth century and torn down before 1880. It likely was built either during Benton Utley’s (1832-1837) or early in Jones Watson’s (1847-1853) ownership of the property.

A reference to this dormitory, with dimensions and method of construction that could be confirmed archaeologically, was found in an 1883 deed, which described the property as “The land whereon formerly stood a row of Brick offices called the ‘Poor House’ One hundred & twenty feet long & Eighteen feet wide on the Extreme Southern end of the lot.” The university had been plagued by shortages of student housing for most of the 1800s, and student letters and diaries of the 1830s and 1840s indicate that housing was at a premium. To help alleviate the problem, many entrepreneurial Chapel Hillians rented rooms or constructed separate buildings in their yards to serve as student quarters.

With the onset of the Civil War, such temporary residences were no longer needed, and during the subsequent Reconstruction period, many fell into ruin and were removed. In discussing conditions in Chapel Hill at this time, Kemp Battle observed that “[a]nother effect of the hard times through which the village passed was the removal of many cottages which had been built by the landowners for the accommodation of students of prosperous days, who were unable to procure lodging in the University Buildings. These cottages were torn down, or sold, some re-erected a mile or so away on the neighboring farms. Thus disappeared from the map ‘Pandemonium,’ ‘Possum Quarter,’ the ‘Poor House,’ ‘Bat Hall,’ the ‘Crystal Palace,’ and other places dear to the ante-bellum students” (History of the University of North Carolina. Volume II: From 1868 to 1912, by Kemp P. Battle, 1912, p. 40).

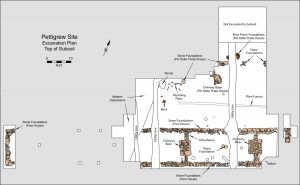

Archaeological investigation of the Pettigrew site began with a combination of methods ranging from systematic soil sampling with a one-inch-diameter auger to assess site stratigraphy, remote sensing with a magnetometer to identify subsurface soil anomalies that might be attributable to building foundations and other soil disturbances, and test excavation to evaluate the artifact content of the underlying soil strata. Artifacts clearly associated with the fraternity house were recovered, and one of the test pits revealed part of the stone foundation that supported the north wall of the Poor House.

Next, much of the site area was stripped of topsoil with a backhoe to expose the top of the underlying undisturbed deposits. These deposits were hand-excavated to recover artifacts, expose building foundations and other identify other archaeological features associated with the fraternity house, the Poor House, and earlier “backyard” activities predating construction of the Poor House.

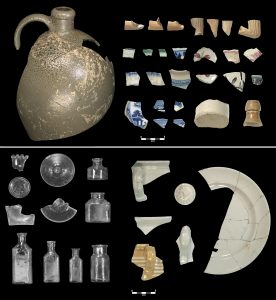

Architectural debris associated with the Poor House was the most extensive and included window glass, cut nails, and brick rubble in addition to stone foundations. Fewer artifacts could be attributed to the fraternity building, perhaps because these items were removed when the university demolished the structure in the 1930s and by mechanical stripping prior to hand excavation. Items clearly associated with this later structure included plumbing pipes and fixtures, electrical insulators, light bulbs, tile, window glass, wire nails, a doorknob, and a door lock. Artifacts associated with the occupations of both buildings included whiteware, porcelain, and stoneware sherds (view a 3D model below), glassware, bottle fragments, lamp glass, personal items, and animal bones. Smaller quantities of creamware and pearlware sherds, some found beneath the Poor House, pre-date both structures and likely are associated with the original occupants of Lot 11 during the late 1700s and early 1800s. Interestingly, numerous shallow plow scars also were observed which cut into the subsoil clay beneath the Poor House. These reflect the property’s use as a garden before the Poor House was constructed.

The physical remains of the Poor House are much more substantial than those of the fraternity and consist of continuous stone foundations for the exterior walls, interior walls, and chimneys. These foundations indicate a building that was 120 ft long and 16 ft wide. Although its width and eastern end were determined fairly early during the excavation, the western end was not located until the 1883 deed was discovered that described the building’s dimensions. The length was then quickly confirmed through excavation. The building had four interior chimneys, and the foundations for two of these were fully exposed. The floor plan consisted of a row of eight rooms that were approximately 15 ft by 16 ft in size, with each room heated by a single fireplace.

Structures similar to the Poor House were built on other southern college campuses during the 1830s. Elm Row (shown at right) and Oak Row, built in 1836-1837 and two of the oldest buildings at Davidson College, were single-story brick structures that originally served as dormitories, and each housed 16 students. This building style apparently was inspired by Thomas Jefferson’s academic village at the University of Virginia.

3D Model of Artifact

Salt-glazed stoneware jug recovered during excavation of the Poor House

Contributor

R. P. Stephen Davis, Jr. (Research Laboratories of Archaeology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill)

*Images courtesy of the North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

**Images courtesy of the Research Laboratories of Archaeology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

***Photograph by Thomas Hargrove, 1997. Courtesy of the Research Laboratories of Archaeology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Sources

Davis, R. P. Stephen, Jr.

2015 • The Hidden Campus: Archaeological Glimpses of UNC in the Nineteenth Century. Gladys Hall Coates University History Lecture, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, April 14, 2015.

Davis, R. P. Stephen, Jr., Patricia M. Samford, and Elizabeth A. Jones

2010 • The Eagle and the Poor House: Archaeological Investigations on the University of North Carolina Campus. In Beneath the Ivory Tower: The Archaeology of Academia, edited by Russell Skowronek and Kenneth Lewis, pp. 141-163. University Press of Florida.

Jones, Elizabeth A., Patricia M. Samford, R. P. Stephen Davis, Jr., and Melissa A. Salvanish

1998 • Archaeological Investigations at the Pettigrew Site on the University of North Carolina Campus, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Research Report No. 20, Research Laboratories of Archaeology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.