MacKnight Shipyard Wreck (Currituck County)

North River, also called Indiantown Creek, provided water transport for ocean-going vessels carrying local agricultural and forest goods from inland plantations to Currituck Sound and beyond. At the center of this maritime trade was the plantation landing and port of entry established by Thomas MacKnight, who moved to the area in 1757.

Local historians Wilson and Barbara Snowden first raised awareness that archaeological remnants of the landing may have survived to present day. When staff from the Underwater Archaeology Branch (UAB) of the Office of State Archaeology arrived in 1992, they found little evidence of the thriving colonial river port that once operated at MacKnight’s plantation. At first glance the area looked like an overgrown swamp, but upon closer examination there appeared to be evidence of former shoreline bulkheads that formed a small basin in the water, perhaps the outline of the old slip where ships were launched after construction.

UAB staff returned to the site the following year with East Carolina University (ECU) student Rick Jones, who wanted to investigate the shipyard for his graduate research project. Using a magnetometer, which can locate items at a greater depth than the conventional metal detector, they identified the remains of a wooden ship lying in shallow waters adjacent to the suspected location of the MacKnight Shipyard. This vessel became the subject of Jones’s Master thesis, leading him to conduct extensive archival research and additional field investigations.

Archaeological Investigations

The MacKnight Shipyard Wreck had potential to provide significant information about plantation-built vessels in the South because written records describing these vessels are rare and few archaeological studies have been conducted on colonial-period shipwrecks in the eastern United States. When archaeologists work in the historic period they use documentary evidence from archives to develop hypotheses regarding what an archaeological site represents. In this case, with a shipwreck found adjacent to a colonial shipyard, the following question arose: Did the sunken ship date to the same period as the shipyard and was it built on-site?

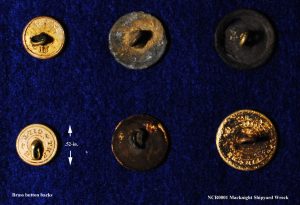

In 1994, UAB staff along with Jones and fellow ECU students returned to the site for a week-long investigation. Archaeologists cleared the area of tree limbs to access the wreck and exposed the hull timbers that comprised the body of the boat. Little excavation was needed. Dredging and screening allowed small artifacts (broken pieces of ceramic and glass and metal objects) to be recovered from sediments deeper in the wreckage. Although scarce, the artifacts dated collectively to the last quarter of the 18th century. Once cleared of debris and sediment, archaeologists mapped the surviving timbers, recorded the boat’s construction features in detail, and took wood samples for further analysis.

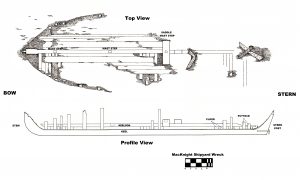

Based on the divers calculations, the MacKnight Shipyard Wreck measured 44 feet, 4 inches in length and 13 feet, 10 inches in width (or beam). These dimensions are consistent with ships built during the late 18th and early 19th centuries in the American South. Entering the measurements into a shipbuilding formula from that period determined that the vessel’s draft, or the amount of water it needed to float, would have been 6 feet. The storage space (known as the depth of hold) measured 4 to 4-1/2 feet below the main deck and held a cargo capacity of 27 tons.

Construction Techniques and Implications

Key construction features of the MacKnight Shipyard Wreck are found in the lower hull and interior framework, which consisted of a longitudinal timber (called a keel) that ran from one end to the other, cross timbers (or floors) placed on top of the keel, and another long timber (the keelson) laid on top of the floors. This assembly, pinned together with wooden pegs (also known as treenails), formed the strength and structure of the ship. Additional frames (called futtocks) and wooden planks were fastened on the outside of the framework to complete the vessel. Tar, pitch, and caulking made the hull water-tight. These and other features conformed to ships built during colonial times, including a framing technique known as “room equal to space” in which the width of the ship’s ribs were the same as the space left open between them. The practice of ending the first futtocks short of the keelson also was a colonial construction technique.

Other construction features of the MacKnight Shipyard Wreck represent techniques used by shipwrights working specifically in the American South, such as tapering the keelson from a square timber to a plank and ending it short of its sternpost. The structural timbers hewn from red cedar provide another important clue that the ship was constructed in the tidewater Virginia and northeastern North Carolina region. Red cedar was abundant in these areas and known for its use in shipbuilding.

One unique and somewhat curious feature of the ship is the fact that it was fitted with three mast steps (square holes cut into in the keelson where the masts were placed). Having three mast steps is unusual for a ship measuring less than 45 feet in length. There is no documentary evidence for this type of ship, nor is it probable that a vessel of this small size could carry three masts. More likely, the three mast steps represent two different periods of service for the vessel. Initially, the vessel was built as a single mast sloop with the mast located in the middle of the ship where the last mast step is located. Sometime later in its life, the vessel was converted to a two-mast schooner with the main mast located in the same position as the sloop, but with the mast step fitted with a saddle. This feature consisted of a short timber (also with a square hole) laid perpendicular to the keelson to add extra support for the mast. Saddle steps were commonly used by both English and American shipwrights during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The forward mast of the schooner rig would have been placed in the mast step closest to the bow, which situated the mast a little more forward than expected for a two-mast vessel based on existing documentation. This construction technique, however, may be unique to southern shipbuilders. The location of the middle mast step was an anomaly based on formulas from historic records. This feature more likely supported the post for a davit, a crane-like device used to load and off-load cargo from the vessel.

Historical Interpretation

The MacKnight Shipyard Wreck, built as a typical 18th-century sloop, was converted later in its service to a schooner, a vessel type that rose in popularity during the latter part of the century. The sunken vessel partially blocks the entrance to the slip, which suggests it was abandoned shortly after shipbuilding and repair operations ceased at the MacKnight Shipyard. Artifacts recovered from the abandoned vessel defined a relatively tight period of service during the 1790s. Brass cuff and coat buttons provided a mean date of 1792.

The archaeological information collaborates what is known historically about economic and political events at the time. Thomas Macknight moved to the area in 1757 and established a thriving plantation, port, and shipyard along with a saw mill and shingle-making business. MacKnight’s shipyard built numerous coastal and ocean-going vessels between the 1760s and mid-1770s. Based on construction details and archaeological evidence, the MacKnight Shipyard Wreck was built just before MacKnight was forced to abandon his property in 1775 and return to England, having been labeled a Tory for being sympathetic to the British Crown. MacKnight’s property sat idle during the Revolutionary War and the years that followed as the economy recovered. In 1787, Thomas Poole Williams purchased the property and resumed shipbuilding operations. At that time, the vessel likely was refurbished and converted to a schooner before being put back in service, where it continued to be used into the 1790s. American shipbuilders prospered, providing ships and supplies to Europe during the French Revolution. By 1807, when President Thomas Jefferson declared an embargo to restrict trade with England, the American economy had collapsed. The resurrected shipyard ceased operations around that time, and the vessel we now know as the MacKnight Shipyard Wreck was laid to rest, eventually sinking below view into the waters of the North River.

Contributor

Mark U. Wilde-Ramsing (Retired, Underwater Archaeology Branch, Office of State Archaeology, North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources)

*Images courtesy of the Underwater Archaeology Branch, Office of State Archaeology, North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources

Sources

Sheridan R. Jones

1996 • Historical and Archaeological Investigation of the Macknight Shipyard Wreck (0001NCR). Unpublished MA thesis, Department of History, East Carolina University, Greenville.

Mark Wilde-Ramsing

1992 • Underwater Archaeological Examination of North River, Currituck and Camden Counties. Manuscript on file with the Underwater Archaeology Branch at Kure Beach, Office of State Archaeology, North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources.