Mississippian (A.D. 1000–1700)

North Carolina is a particularly interesting area as it represents a boundary for the extent of Mississippian influence in the Southeast. In the Appalachian Summit, this is termed the South Appalachian Mississippian tradition and is characterized by complicated-stamped ceramics, stockaded villages, substructure mounds, and agricultural economies.. The emergence of Mississippian culture in the Appalachian Summit is abrupt and a hypothesis of extended, in situ cultural evolution is tenuous – instead it looks like Mississippian peoples actually moved into this region. In the Southern Piedmont, we see Mississippian-influenced societies – groups that specifically do not participate in the Piedmont Village Tradition evidenced throughout the rest of the state. As a result of this cultural split in the Appalachian Summit and the Southern Piedmont, the late Woodland technically ends at A.D. 1000, whereas in the rest of the state the Late Woodland continues until the Historic period.

The South Appalachian Mississippian tradition, with its complicated-stamped ceramics, stockaded villages, substructure mounds, and agricultural economy appeared shortly after A.D. 1000. The emergence of Mississippian culture in the Appalachian Summit is abrupt and a hypothesis of extended, in situ cultural evolution is tenuous.

Pisgah phase (A.D. 1000 – 1450)

Pisgah phase people’s dependence on agriculture and their construction of elevated platform mounds upon which temples or chiefly residences were built mirror important changes in sociopolitical organization. Extensive excavations at two sites, Warren Wilson and Garden Creek, make the Pisgah phase one of the best understood cultural complexes in the Appalachian Summit.

Most Pisgah sites are located in the eastern and central portions of the Appalachian Summit, and the largest concentration is found in the Asheville, Pigeon, and Hendersonville intermontane basins.

Pisgah settlements are characterized by a variety of sizes, ranging from small farmsteads to fairly large nucleated villages that sometimes have substructure mounds. Warren Wilson seems to be a typical middle-sized Pisgah village of three acres. It is surrounded by at least seven palisade lines, most of which probably represent expansion over time. A near absence of storage pits at Warren Wilson site may indicate that Pisgah people preferred aboveground storage cribs and granaries. Use of such facilities has been documented for the Historic Cherokees and other southeastern Indians. However this pattern stands in sharp contrast to the Piedmont Siouans, who made extensive use of underground storage.

Pisgah houses were roughly rectangular and measured about 20 feet on a side. Walls were constructed by setting individual posts in holes. Most houses had central hearth basins with prepared clay collars. Half of the Warren Wilson Pisgah houses had parallel entry trenches.

The most striking pit features at Warren Wilson were large shallow depressions around the edge of the village near the palisades. These facilities sometimes measured over 10 feet long and five feet wide, but less than a foot deep, and their bottoms were lined with a thin layer of clay. These have been interpreted as roasting pits, perhaps for community celebrations.

Most graves were placed inside or adjacent to houses. Individuals were buried with their heads oriented in a westward direction and placed in a flexed position in simple, straight sided pits or shaft and chamber pits.

Funerary objects, when present, usually consisted of ornamental items made from shell (e.g., beads, gorgets, and ear pins), animal bone (e.g., turtle-shell rattles and beads), or mica (e.g., plates and disks). Only two burials contained non-ornamental artifacts, a small conch shell, a conch-shell bowl, bone awls, red ocher, fish scales, and panther claws.

Pisgah pottery types are easily distinguished from earlier and later pottery of the Appalachian Summit. Collared rims and rectilinear complicated-stamped vessel surfaces set Pisgah sherds apart. This rim form has no precedent in western North Carolina or the surrounding area. However, similar forms have been found in the Iroquois area of western New York and southwestern Ohio, and similarities to the Oliver phase in Indiana have been noted.

Likewise, the complicated-stamped designs commonly found on the surfaces of Pisgah vessels show no close affinities to earlier local types, although connections to Pisgah rectilinear complicated-stamped designs are found in Napier, Etowah, and Woodstock ceramic traditions of northern Georgia.

Changes in Pisgah ceramics through time point to a continued flow of ideas from the south into the central North Carolina mountains, a flow that continued as the Lamar phase of northern Georgia merged with local ceramic traditions to form the Protohistoric/Historic Qualla phase (see below).

Other artifacts that reflect an influx of new ideas with the Pisgah and Qualla phases include clay pipes, polished stone discoidals, and stone celts.

Like other Woodland and Mississippian cultures of North Carolina, Pisgah folks took full advantage of their natural environment by consuming a variety of wild animal and plant foods. Deer, bear, and wild turkey were important. Interestingly, large numbers of toad remains, probably for ceremonial or hallucinogenic purposes, have been found in both Pisgah and Qualla sites.

In the bottomlands near their villages, Pisgah people planted fields of corn, beans, squash/pumpkin, and sumpweed. As much as half of Pisgah subsistence was derived from agriculture, a major shift in the importance of agriculture from the preceding Connestee phase.

Pisgah phase people’s dependence on agriculture and their construction of elevated platform mounds upon which temples or chiefly residences were built mirror important changes in sociopolitical organization.

The Garden Creek site complex is on the Pigeon River in Haywood County. Garden Creek Mound No. 1 was constructed during the Pisgah phase and associated with a large village. The sequence of events for the mound tells us a great deal about Pisgah ceremony and social organization.

Before the mound was begun, two semi-subterranean earth lodges were built side by side with a passageway between them. Along with a large arborlike building around the earthlodges, the buildings were probably used for communal gatherings. Later constructions added soil to the flanks of the earthlodges and, after their collapse, capped them with a mound. Then two structures, a palisade, and a number of burials were placed on the mound. Over half of the burials, much more than Warren Wilson site Pisgah burials, were accompanied by grave goods, such as columella beads, tubular shell beads, shell gorgets, and shell ear pins.

The changes in form and structure between the Middle Woodland Connestee phase mound (Mound No. 2) and Pisgah phase mound (Mound No. 1) at Garden Creek site suggest fundamental difference in political organization and ceremonial practice. The Connestee phase mound started as a low platform to support a wall-post structure, and the succeeding stage of construction duplicated this function. Numerous hearths and refuse pits, indicating communal feasting, were present, but no Connestee burials were found on the mound.

In contrast, Pisgah peoples initially built earth lodges for ritual and civic functions. The remains of these lodges were covered by elevated platforms where temples or chiefly residences and numerous burials were placed. This seems to reflect a shift to a more hierarchical form of political organization. These political and ritual changes, shared by other South Appalachian Mississippian mound sites in Georgia, South Carolina, and the North Carolina Piedmont, do not seem to derive from earlier Middle Woodland mound-building.

Although these changes continued in the Qualla phase, Pisgah and Qualla phase cultures were at the low end of the scale of sociocultural complexity during the period of major Mississippian influence across the Southeast.

The chronological and cultural relationships between Pisgah, Qualla, and Lamar phases are indirectly addressed by sites in the Catawba River valley, where temporal overlap forces a re-examination of the traditional view of a Pisgah-to-Qualla developmental sequence.

Lamar Culture and the Qualla phase (after A.D. 1350)

Qualla phase is a manifestation of the widespread Lamar culture found across the northern half of Georgia and Alabama, most of South Carolina, and eastern Tennessee. Qualla phase in the Appalachian Summit falls within the Middle Lamar and Late Lamar periods, continuing until the time of sustained European contacts with Historic period Cherokees. This is contemporaneous with the Tugalo and Estatoe phases of north Georgia.

Whereas most Pisgah settlements are in the eastern and central North Carolina mountains, most Qualla sites are concentrated in the western and southern mountains, in the Little Tennessee and Hiwassee drainages. Settlements of both phases are found in the central mountains along the Pigeon, Tuckasegee, and Oconaluftee rivers.

Previously, it was thought that Pisgah preceded and lead to the Qualla phase throughout the North Carolina mountains, however, this view is no longer tenable. Although it has not yet been identified, early Qualla (or Lamar) phase culture was in the western mountains when early Pisgah influences were felt in the central portion of the Appalachian Summit.

Like Pisgah phase, Qualla phase has artifacts that reflect an influx of new ideas to the Appalachian Summit, including clay pipes, polished stone discoidals, and stone celts.

Although the earliest Qualla materials are probably yet to be discovered, the Middle Qualla begins around A.D. 1450 and ends around A.D. 1700. Late Qualla is the period of the Cherokees’ sustained contact with Europeans.

Middle Qualla phase vessels are most often stamped with a carved wooden paddle. Rectilinear-stamped and curvilinear-stamped designs are present, with the latter becoming more popular later. Concentric circle, figure nine, parallel undulating line, chevron, and rectilinear line block or herringbone were popular motifs.

Cazuela bowl forms appear during the Middle Qualla phase with incised designs around the bowls’ shoulders. Incised designs of Middle Qualla appear most similar to the Middle Lamar Tugalo phase of northern Georgia.

Although some earlier Qualla phase platform mounds were constructed and used as summits upon which chiefs resided, later Qualla mounds resulted from accumulations of the rubble and debris of successive town house structures built on the same location. Additional soil was added only to flatten the ground surface so new town houses could be erected.

Excavations at Coweeta Creek site on the Little Tennessee River in Macon County, found six separate town house floors stacked one atop the other, separated only by a few inches of sand and refuse. European trade artifacts were found in association with all but the earliest townhouse floor.

Middle Qualla phase houses excavated at Coweeta Creek were identical in size and shape to Pisgah houses at Warren Wilson site. They were rectangular, a little over 20 feet on a side, and had vestibule entrances and interior supports.

At Coweeta Creek the excavated village predated the later stages of the town house construction. After European contact, Qualla settlements appear to have become more dispersed. However, the continued use of the Coweeta Creek mound and town house during the Historic period indicates a strong sense of community.

Most graves were placed in the village area, often associated with houses. But groups of graves were found on either side of the town house entrances. The presence of these burials strongly suggest that these individuals were important members of the community. Both males and females, as well as children, were present. Townhouse area burials with the most elaborate offerings were males, interpreted as town leaders. Among those burials found throughout the village, women had more elaborate offerings, suggesting that they filled the roles of clan leaders.

Overall, burials with grave offerings were accompanied with artifacts of shell, including cut shell beads, olivella beads, ear and hair pins, engraved gorgets, pendants, and masks. Other grave offerings were stone and clay pipes, pottery vessels, red ocher, and freshwater pearls.

In general, later Qualla and Lamar cultures appear to have become more egalitarian, with authority becoming grounded in community consensus. The town house became the focal point for the community. where decision-making was opened up to a large segment of the population, which was represented by clan leaders.

Farming continued to be the most important subsistence activity. Corn, beans, squash, pumpkins, and gourds were planted in the fertile alluvial soils, and a wide variety of seasonally available foods and wild animals added to the diet.

The Eastern Fringe of the Appalachian Summit (after A.D. 1350 to Historic period Cherokee)

The chronological and cultural relationships between Pisgah, and Qualla and Lamar phases are further addressed by sites in the Catawba River valley, where temporal overlap forces a re-examination of the traditional view of a Pisgah-to-Qualla developmental sequence.

Archaeologists believe that during the time of the Pisgah and Qualla phases in the Appalachian Summit, the people who lived below the Blue Ridge in the Upper Catawba River basin in Burke and McDowell counties show affinities to both the prehistoric Cherokee and the Catawba. Two archaeological sites, the McDowell site in McDowell county and the Berry site in Burke county, illustrate the complexities of the period.

According to David Moore’s 2002 volume “Catawba Valley Mississippian” the McDowell site is a relatively large village dating to the Pleasant Garden phase in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries (A.D. 1400 – 1600) whose people participated in regional activities with Pisgah phase people to their west and Burke phase people to their east.

Excavations at the Berry site revealed a major Burke phase component with similarities to Middle Lamar phases in Georgia and the Middle Qualla phase in the Appalachian Summit also dating to the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Because inhabitants of McDowell site interacted with both Pisgah-like people to their west and Qualla/Lamar related people to their east at Berry site, they illustrate the problem with viewing Pisgah and Qualla phases in the Appalachian Summit as purely sequential developments.

Moore notes that the broader interactions of Burke phase and other surrounding late prehistoric groups make it clear “that groups practicing South Appalachian Mississippian lifeways occupied not only the south-central Piedmont of North Carolina (Pee Dee culture), but an equally large portion of the western Piedmont region as well.”

Close South Appalachian Mississippian Tradition

The southern Piedmont region is archaeologically unique within North Carolina. During most of Late Woodland times cultures here did not participate in the Piedmont Village Tradition. Instead they were influenced by South Appalachian Mississippian.

Between A.D. 1000 and 1400, Mississippian-influenced societies developed from the coast of Georgia to the mountains of North Carolina. Known archaeologically as Etowah, Wilbanks, Savannah, Pisgah, Irene, and Pee Dee, these politically complex cultures build mounds for the elite, participated in elaborate ceremonialism, and sometimes ruled over large territories.

Pee Dee Culture (A.D. 1000 – 1500)

In the southern North Carolina Piedmont, the expression of the South Appalachian Mississippian tradition is the Pee Dee culture. The Town Creek site, on the Little River in Montgomery County is the most important Pee Dee site. Once thought to be a movement of people that arrived in the Piedmont with an entirely new way of life, Pee Dee is now viewed as a regional center of South Appalachian Mississippian that interacted and evolved with other regional centers scattered from the Coastal Plain of Georgia and South Carolina to the western North Carolina mountains.

The Town Creek site is located on the Little River near its confluence with Town Fork Creek in Montgomery County. Excavations at Town Creek began in 1937 and continued off and on for the next fifty years. Designated a state historic site in 1955, Town Creek remains today North Carolina’s only state historic site dedicated to its native population.

The mound at Town Creek faced a large plaza where public and ceremonial activities took place. Several structures, including some that may have served as burial or mortuary houses, were constructed around the edge of the plaza.

The mound was constructed over an early rectangular structure described as an earth lodge. After this structure collapsed it was covered with a low earthen mound that served as a platform upon which a temple was erected. After this structure burned a thick layer of soil was added to enlarge and heighten the mound and another temple was built. The mound, plaza, and habitation zone were enclosed by a stockade made of closely set posts. There were five episodes of stockade building.

Although not visible like the mound, a large number of burials were present at Town Creek. Several were clustered in mortuary areas. Most were loosely flexed and placed in simple pits. A few were fully extended or reburied as bone bundles. Several infants and small children were tightly wrapped and buried in large pottery vessels – called burial urns. A few of the Pee Dee burials were richly adorned with a variety of exotic artifacts made from copper and shell. Copper artifacts include copper-covered wooden ear spools and rattles, pendants, sheets of copper, and a copper axe. Beads, gorgets and pins were fashioned from conch shell.

There are strong similarities between Pee Dee pottery and pottery from other South Appalachian Mississippian sites in South Carolina and Georgia. The ceramics most similar to Town Creek pottery came from the Irene site near Savannah, Georgia.

Earlier pottery at Town Creek is more often hemispherical bowls and jars with complicated stamped surfaces. The most popular early designs are a series of concentric circles, followed by filfot cross designs. The filfot cross later replaced concentric circles as the more popular surface finish. Plain and burnished surface treatments increased and cazuela bowls became more popular. Another treatment, textile wrapping, appears late and is unique to Pee Dee pottery.

Pee Dee Culture at Town Creek did not suddenly appear but evolved over a period at least 200 years. The fourteenth century saw the decline of many South Appalachian centers like Irene and Town Creek. As temple mounds were abandoned, burial practices changed to reflect a more egalitarian society. Focusing on outlying villages without mounds clarifies Pee Dee Culture before and after Town Creek.

Teal Phase (c. A.D. 1000 – 1200)

Early Pee Dee culture began between A.D. 980 and 1160. Pee Dee complicated stamped pottery was accompanied by fine-cordmarked and simple stamped types called Savannah Creek. Subsistence was based on hunting, fishing, and farming. Little is known of domestic architecture, although some ceremonial structures and burials have been found.

Town Creek phase (A.D. 1200 – 1400)

This is the time when the mound was constructed at Town Creek and the site became the ritual and ceremonial center of the Pee Dee drainage. A substantial residential population was present at the site. Although maize agriculture was a mainstay, hunting, fishing, and gathering remained important. Except for the elaboration of ritual activities, Pee Dee culture continued much as before.

Leak phase (ca. A.D. 1400 – 1500)

As Town Creek’s importance began to wane around A.D. 1400, the Leak site grew in size and importance. The popularity of complicated stamped, plain, and textile wrapped surfaces and cazuela forms increased. Oval houses were constructed. Subsistence practices changed little.

Caraway Phase (A.D. 1500 – 1700)

Following the end of Pee Dee Culture in the southern Piedmont, the Caraway phase represents a return to the mainstream of the Piedmont Village Tradition. Only a few vestigial ceramic traits and abandoned villages remained to hearken the accomplishments of the Pee Dee Culture.

Caraway phase was first recognized at the Poole, or Keyauwee site, on Caraway Creek in Randolph County. Although a few European trade artifacts are found at Keyauwee, most of the materials date to late in the Late Woodland period – around the beginning of the sixteenth century. The shell and bone artifacts are very similar to the grave goods found at sites dating to the Hillsboro, late Dan River, and Early Saratown phases.

Caraway phase is the southern Piedmont’s version of the widespread Lamar style. Caraway ceramics represent the culmination of the Badin, Yadkin, Uwharrie, and Dan River ceramic traditions with an overlay of some Pee Dee influence. Smooth or burnished surfaces predominate, followed in popularity by complicated-stamped and simple stamped surface treatments. The smooth and burnished types probably date later than the stamped treatments.

Excavations at Keyauwee site in the 1930s found pits with village refuse in the western portion of the site and burials in the eastern portion. Individual burials were placed in flexed position and accompanied with a variety of artifacts, including bone and shell beads, shell gorgets, stone discoidals, and a stone pipe. The stone pipe is very similar to one found at the Gaston site.

Close Late Woodland Southern Piedmont

- Pisgah series pottery fragments from the Warren Wilson site in Buncombe Co., NC

- Pisgah series pottery fragments from the Warren Wilson site in Buncombe Co., NC

- Pisgah clay pipes from the Warren Wilson site in Buncombe Co., NC

- Chipped-stone arrow points from the Warren Wilson site in Buncombe Co., NC

- Bone awls from the Warren Wilson site in Buncombe Co., NC

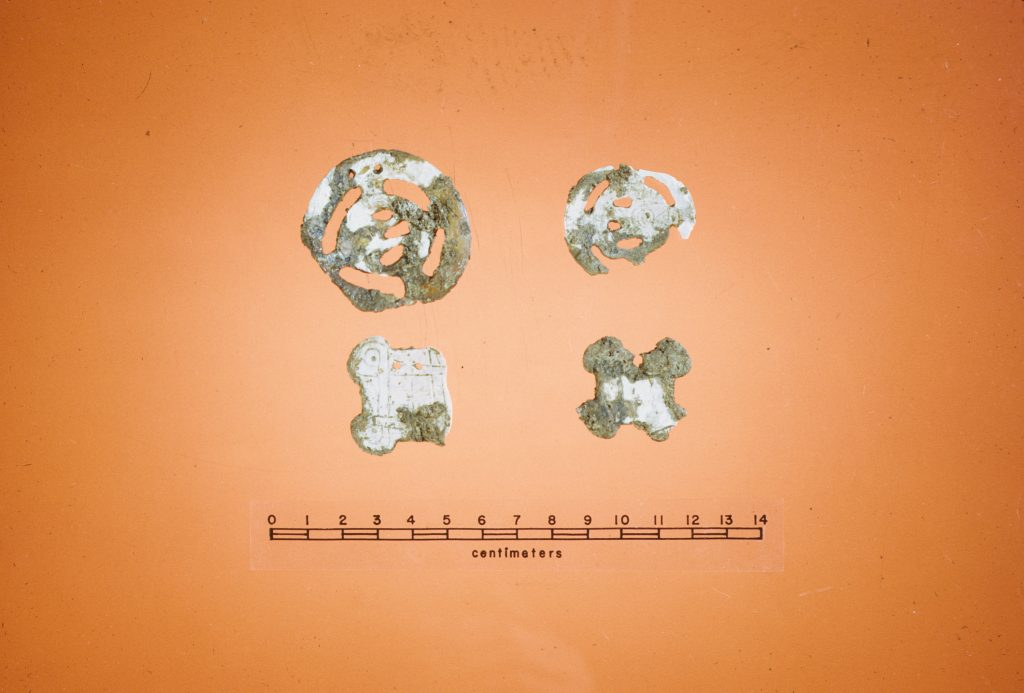

- Shell gorgets from the Warren Wilson site in Buncombe Co., NC

- Shell gorgets from the Warren Wilson site in Buncombe Co., NC

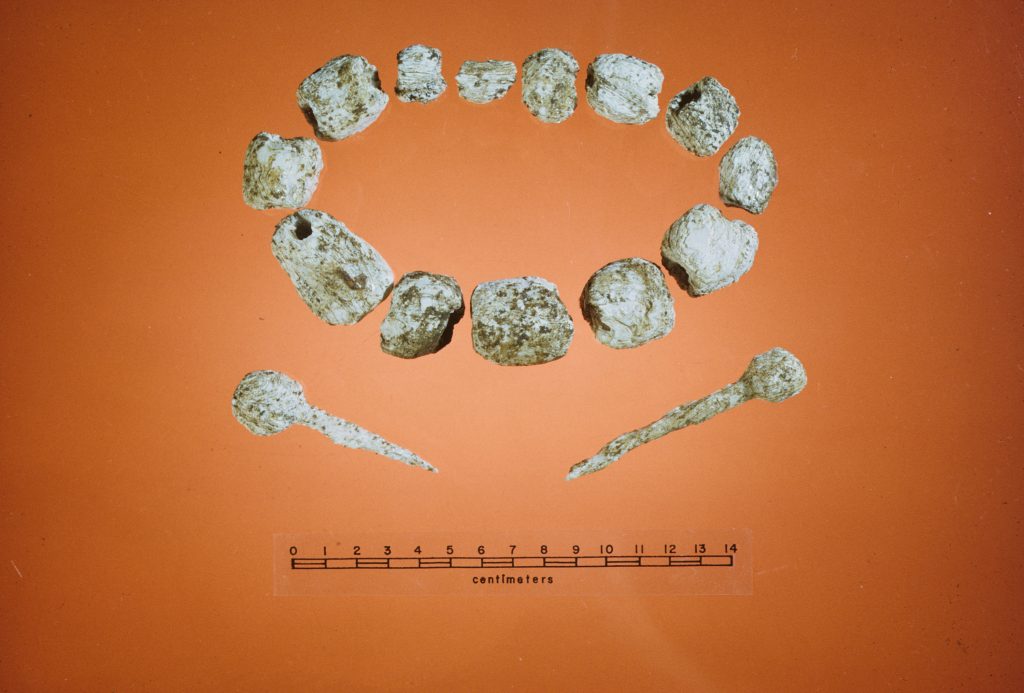

- Shell beads and gorget from the Warren Wilson site in Buncombe Co., NC

- Shell beads and pin from the Warren Wilson site in Buncombe Co., NC

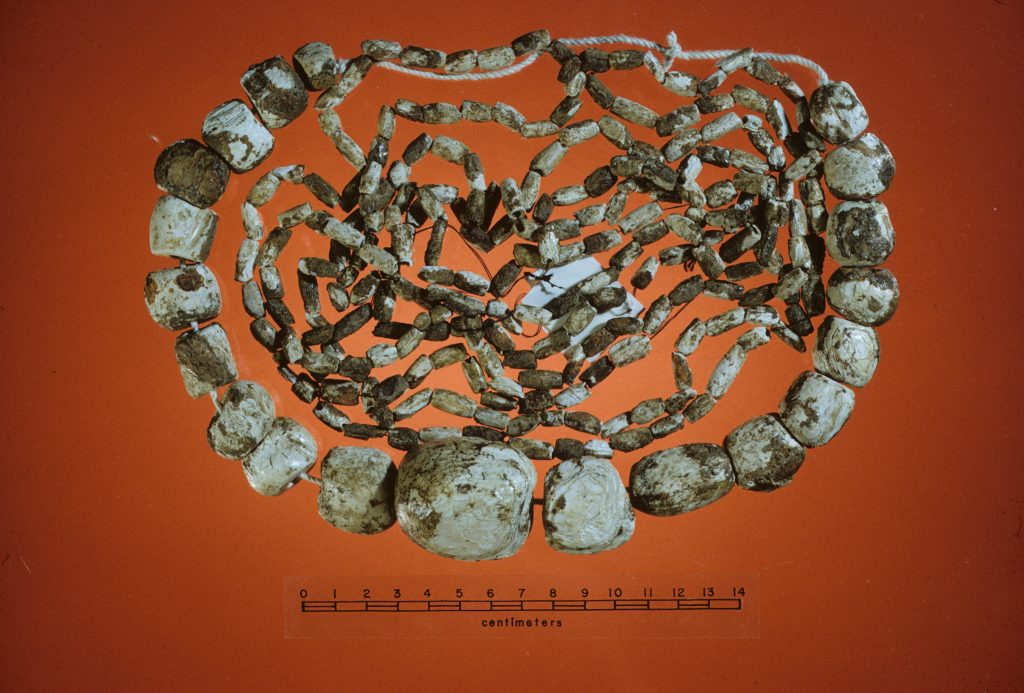

- Shell beads from the Warren Wilson site in Buncombe Co., NC

- Small Pisgah jar from the Warren Wilson site in Buncombe Co., NC

- Duck effigy pipe from Cherokee Co., NC