Woodland (1000 B.C.–c. A.D. 1600)

Three interrelated innovations marked the end of the Archaic and the beginning of the Woodland: pottery-making, semi-sedentary villages, and horticulture. All had their origins in the Archaic but became the norm during Woodland times.

The widespread appearance of pottery-making is viewed as going hand in hand with an increasing reliance on seed crops and more permanent settlement. Domestication of early cultigens laid the groundwork for later acceptance of tropical cultigens. Corn was not widely grown until after A.D. 700 and did not become an important food crop in many areas until after A.D. 1000. With the introduction of beans around A.D. 1200, the eastern agricultural triad of corn, beans, and squash was completed.

Early Woodland (1000 – 300 B.C.)

Warren Wilson (Buncombe County)

Middle Woodland (300 B.C. – A.D. 800)

Baum (Currituck County)

Broad Reach (Carteret County)

Garden Creek Mound #2 (Haywood County)

Jordan’s Landing (Bertie County)

Late Woodland (A.D. 800 – 1650)

Cold Morning (New Hanover County)

Donnaha (Yadkin County)

Garbacon Creek (Carteret County)

Gaston (Halifax County)

Jordan’s Landing (Bertie County)

Lower Saratown (Rockingham County)

McLean Mound (Cumberland County)

Wall (Orange County)

During the Late Archaic period, people living along the south Atlantic coast from Florida to North Carolina had begun to make fiber-tempered pottery. Stalling series pottery, made by molding lumps of clay and fibrous material into simple vessel forms , was made as early as 2500 B.C. By the beginning of the Woodland period in North Carolina, several different ceramic traditions had been established across the state.

In North Carolina, the Woodland is divided into Early, Middle, and Late periods. Along the coast and through much of the Piedmont, the Late Woodland continues until Contact, while in the Appalachian Summit, Western Foothills, and the Southern Piedmont, Mississippian and Mississippian-influenced societies developed after A.D. 1000.

The Woodland cultures of the North Carolina Piedmont were only marginally influenced by cultural traditions elsewhere in the eastern United States. The rich and elaborate Hopewell and Swift Creek cultures that influenced wide areas of the Southeast had little impact on cultural developments in the Piedmont. And the powerful Mississippian chiefdoms that later dominate most of the Southeast were only able to penetrate the southern fringe of the Piedmont.

Close Regional Evidence

The North Carolina Coastal Plain and Coast are divided into northern and southern parts. In terms of subsistence, the northern region provided far better access to estuarine resources than the south, but the south offered an environment better protected against the extremes of wind and cold.

The Woodland in the Coastal regions of North Carolina was marked by continuity, and the changes that occurred were typically gradual in nature. There were few differences between Late Archaic and Early Woodland cultural traditions and Woodland changes in technology, subsistence, and political organization seem almost imperceptible, reflecting few outside influences. Differences between Middle Woodland and Late Woodland cultural patterns are sharp, but then from A.D. 800 until the first contacts with Europeans was again a period of stability and continuity.

Early Woodland (1000 – 300 B.C.)

Most of what is known about the Early Woodland period in the coastal regions comes from ceramic studies. The earliest ceramics in North Carolina are typologically similar to Late Archaic Stallings-ware pottery of the Georgia and South Carolina coasts

Antecedents to Early Woodland Pottery

Fiber tempered Late Archaic Stallings Island pottery is found as far north as the Tar and Chowan River drainages, but is generally restricted to south of the Neuse River. In the Middle Atlantic region, the earliest pottery is a steatite-tempered ware called Marcy Creek and similar sherds have occasionally been found north of the Neuse River.

Thom’s Creek pottery, which is generally thought to be roughly contemporaneous with Stallings ware, has only been reported from the Southern Coastal region.

Deep Creek and New River Phases

At the beginning of the Early Woodland period, pottery made with a sand-tempered paste and a cordmarked exterior began to be made throughout the Coastal region.

In the north, this pottery is called the Deep Creek series. The Deep Creek series is related to the Stony Creek series of southern Virginia. Large triangular points similar to the Roanoke Triangular type at the Gaston site are believed to be associated with Deep Creek ceramics.

In the Southern Coastal Plain, the New River pottery series is thought to date to the same time period as Deep Creek. Although the vibrant Early Woodland Deptford ceramic tradition borders New River phase to the south, Deptford influences are not apparent.

Much more information is needed before Deep Creek and New River phases can be firmly defined along the coast.

Middle Woodland (300 B.C. – A.D. 800)

Two Middle Woodland phases have been defined in North Carolina’s coastal regions: Mount Pleasant and Cape Fear. Mount Pleasant is the phase that is connected with the Northern Coastal Region. Mount Pleasant pottery is tempered with sand and varying amounts of grit and pebble-sized particles. Surface finishes include fabric impressed, cordmarked, net impressed, and smoothed.

Mount Pleasant pottery is similar to the Early Woodland Deep Creek ware, which it probably descends from directly.

Sites that contain Mount Pleasant ceramics have been found in both the Tidewater and the inner Coastal Plain of the Northern Coastal region. Most coastal sites are large shell middens occupied repeatedly by extended family groups, where exploitation of terrestrial resources was secondary to shellfish collecting and fishing. No Mount Pleasant sites have been sufficiently excavated to understand how large they were or what they looked like.

Flexed and semiflexed graves have been found at Mount Pleasant sites. One grave in Bertie County was accompanied by seven small triangular arrowpoints.

Late Woodland Period (A.D. 800 – 1650)

During the Late Woodland period, physical, cultural, and linguistic differences emerged that can be traced to the ethnohistorically documented tribes who occupied the coast at the time of European contact.

Along the entire length of the coastal Tidewater region of North Carolina, the Late Woodland period is marked by the introduction of shell-tempered pottery. In the Northern Coastal region this practice continued into the Historic period. Late Woodland people of the inner Coastal Plain made pottery that was more similar to that of their Middle Woodland ancestors, with small pebbles added as temper.

The region from the Tidewater coast to the barrier islands, and from Virginia to as far south as Onslow County, was dominated by Algonkian-speaking groups. These groups were responsible for most of the shell-tempered pottery along the coast.

In the Northern Coastal region, the Algonkians were bordered on the west by the Iroquois-speaking Tuscarora tribes. Occupying the inner Coastal Plain from the fall line to the Tidewater, the Tuscaroras made pebble-tempered pottery.

In the Southern Coastal region were Siouan-speaking peoples related to the hill tribes of the Piedmont, whose ceramic traditions are less understood.

Colington Phase (A.D. 800 – 1600)

The distribution of shell-tempered Colington phase ceramics coincides with the coastal Algonkians known to have lived north of Onslow County.

Colington series pottery is typically fabric impressed, simple stamped, or plain. Incised decorations are often placed near the vessel rim. Colington pottery is closely affiliated with the Townsend series and Roanoke Simple Stamped ceramics in southwestern Virginia.

Colington phase sites contain a variety of stone, bone, and shell artifacts. Small triangular arrowpoints, polished celts, abraders, and grinders are fashioned from stone. Fishhooks, punches, awls and pins are made from animal bone. Conch shells are used for hoes and picks. Marginella shell beads are common, and freshwater pearls and a copper disk have been reported.

The nature of Colington phase settlements over the 800 years that comprise the phase is difficult to characterize. Maize farming probably became important sometime after A.D. 1100 and larger populations with complex societies developed after A.D. 1200 or later. By the time of earliest European contact, the Algonkians had grown into ranked societies or chiefdoms, each with a hereditary ruler who lived at the capital village of his territory.

The average Algonkian town at the end of the sixteenth century may have contained twelve to eighteen longhouses, with a population of roughly 120 to 200 people. The towns were located along major streams, sounds, and estuaries where subsistence tasks, including farming, hunting, gathering, fishing, and shellfish collecting were carried out.

Two traits stand out in defining these coastal Algonkians – longhouses and the practice of burying large numbers of people in mass graves or ossuaries after exposure of the dead in a charnal house.

There are excellent descriptions and drawings of North Carolina Algonkian communities in the Northern Coastal region. These were provided by English explorers between A.D. 1584 and 1587. The village of Pomeiock (Pomeiooc), for instance, was located on the mainland side of Pamlico Sound next to Lake Mattamuskeet. This village consisted of a tight cluster of longhouses in a concentric circle within a stockade surrounding a central plaza.

In contrast, the village of Secoton was located on the bank of the Pamlico River. This village had an open arrangement of longhouses. Individuals are depicted in various activities, including praying, dancing, and eating. Three cornfields with crops in various stages of maturity are shown.

A great deal of archaeology still needs to be done on Colington phase villages to integrate the historic records and archaeological record.

Close Coastal Plain and Coast

Piedmont Tradition Early and Middle Woodland Periods (1000 B.C. – A.D. 800)

Although we know relatively little about their origins during the Early Woodland period, cultures throughout most of the Piedmont steadily evolved along an unbroken continuum from about A.D. 1000 until the time of first contacts with Europeans. Subsistence seems to have remained evenly balanced between crop production and wild plant and animal resources. Social distinctions were based primarily on age and sex. Egalitarian Woodland societies were woven together by kinship and leadership roles were achieved rather than ascribed.

Only in the Southern Piedmont is the Piedmont Village Tradition broken by the spread of the South Appalachian Mississippian tradition into the Yadkin-Pee Dee River Valley.

The stratigraphic and stylistic relationships among various ceramic types during the first half of the Woodland period are still unclear. Badin, Yadkin, Vincent, and Clements series ceramics are guides to occupations of the Piedmont during this time.

Aquatic resources are important during this time and a wide variety of mammals and birds were eaten. Several species of weedy plants, including maygrass, knotweed, goosefoot, and sunflower, although no direct evidence of these practices have yet been found in the Piedmont.

During this time the bow and arrow completely replaces the atlatl.

Badin Phase (c. 500 B.C. ?)

The Badin phase is named for the small Stanly County town. Near Badin, at the Doerschuk site, the Badin ceramic series was found in a soil zone overlying the Late Archaic Savannah River level. Badin vessels, well-made and tempered with sand, were simple in form, consisting of straight-sided jars with conical bottoms. Vessels were stamped with cord-wrapped and fabric-wrapped paddles. Badin ceramics appear to be related to the Early Woodland Deep Creek wares of North Carolina’s coastal region.

In addition to the abrupt introduction of ceramics, an entirely different form of projectile point was thought to be associated with the Badin Phase. Crudely flaked, triangular “Badin” points represent quite a departure from the large, stemmed spear points of the Savannah River phase. Based primarily on radiocarbon dates for the succeeding Yadkin phase, archaeologists think that the Badin phase must date to around 500 B.C. One thing that is surprising in the North Carolina Piedmont is the small number of Badin and Yadkin phase sites compared to the relatively large number of Late Archaic Savannah River phase sites.

Otherwise, we know very little about aboriginal life styles during the Badin Phase. Probably very little changed from the Late Archaic period except for the gradual incorporation of the bow and arrow and ceramic containers. Technology was still primarily adapted to a hunting-and-gathering way of life.

Yadkin Phase (c. 300 B.C. – c.A.D. 800?)

The Yadkin ceramic series, which is thought to follow after Badin ceramics, was also defined at the Doerschuk site. Yadkin is similar to Badin except for being tempered with crushed quartz. Cord-wrapped and fabric-wrapped surfaces persist, but new kinds of surface treatments – check stamping, linear check stamping, and simple stamping made with carved wooden paddles – are added. These treatments tie Yadkin phase pottery to the Early Woodland Deptford wares common in Georgia in South Carolina. Yadkin projectile points are typically large triangular forms that resemble Badin points but are more finely flaked.

Radiocarbon dates for Yadkin and Yadkin-like ceramics generally fall between 290 B.C. and A.D. 60, so it is unclear whether Badin ceramics predate Yadkin in all areas of the Piedmont. Some Yadkin sites may have been occupied for relatively long periods of time and lasted until the latter part of the phase, around A.D. 500.

Yadkin phase sites occur more frequently than Badin phase sites, especially in the Southern Piedmont and the South Carolina Coastal Plain. Still, evidence relating to the way Yadkin people lived are rare. As Early Woodland research continues across the Piedmont, we will probably see more and more variability in the early ceramic traditions and find that what holds true for one region may not hold true for another.

Piedmont Tradition Late Woodland Period (A.D. 800 – 1600)

The Late Woodland across the Piedmont begins with the Uwharrie phase. After A.D. 1100, major cultural changes took place as regional manifestations of the Piedmont Village Tradition emerged. The local expression of the Piedmont Village Tradition in the Northwestern Piedmont is the Donnaha phase.

Cultures throughout most of the Piedmont steadily evolved along an unbroken continuum from about A.D. 1000 until the time of first contacts with Europeans. Subsistence seems to have remained evenly balanced between crop production and wild plant and animal resources. Social distinctions were based primarily on age and sex. Egalitarian Woodland societies were woven together by kinship and leadership roles were achieved rather than ascribed.

Even though there were no sharp breaks or glaring innovations with the beginning of the Late Woodland period in Piedmont North Carolina, major cultural changes took place between A.D. 1100 and 1600 as regional manifestations of the Piedmont Village Tradition emerged. This was a time of population consolidation and the beginning of intertribal conflicts. In much, but not all, of the Piedmont, larger villages surrounded by stockades protected inhabitants. This was probably the result of increased agricultural production and efficiency, and competition for good agricultural lands.

Establishing linkages between archaeological complexes and specific tribal groups is often difficult and sometimes impossible. There is, however, a marked increase in the diversity of the archaeological record throughout the Piedmont during the latter half of the Late Woodland period. Much of that diversity no doubt coincides with ethnic and tribal differences taking shape at this time. The Dan River and Saratown phases probably represent people ancestral to the Sara Indians. Along the Eno River, the Hillsboro phase may be related to the Eno, Shakori, and Occaneechi tribes. Further south, in the Haw River, the Haw River, Hillsboro, and Mitchum phases are possibly linked to the Sissipahaw Indians. The Gaston phase may represent the Occaneechis, Tutelos, and Saponis.

The Southern Piedmont saw the arrival of the Pee Dee culture – mound builders with a highly stratified and politically complex society. Pee Dee culture shares more traits with the Pisgah phase of the Appalachian Summit than the Siouan cultures of the Piedmont. Both were part of the South Appalachian Mississippian cultural tradition.

Uwharrie Phase (A.D. 800 – 1200)

The Uwharrie phase, with sites throughout central North Carolina, is the “mother” of all succeeding phases of the Piedmont Village Tradition. Although named for the Southern Piedmont, Uwharrie phase sites are distributed throughout central North Carolina.

The relatively small Uwharrie villages are more sedentary than during the preceding Woodland periods. Increased reliance on domesticated plant foods is reflected in the archaeobotanical record, the large subterranean storage facilities, and the phase’s typical large conical jars.

Hunting, gathering, and fishing were still the mainstays of Uwharrie subsistence, but garden crops, including corn, became important, particularly towards the end of the Uwharrie phase.

Uwharrie pottery continued in the same basic tradition as the Badin, Yadkin, Vincent, and Clements styles, although vessel surfaces were finished with a coarse, net-like material and Uwharrie potters began to decorate their pots with crudely incised parallel lines.

Burials, placed in simple oval pits, were sometimes adorned with shell beads and other ornaments, and placed in cemetery-like areas away from the main habitation area.

From this widespread pattern of Uwharrie adaptation emerged the riverine-focused, nucleated settlements that characterized the last half of the Piedmont Village Tradition.

Haw River Phase (A.D. 1000 – 1400)

Haw River phase sites are restricted to the Central Piedmont. The Hogue and Wall sites, on the Eno River near Hillsboro, demonstrate the transition from small scattered settlements to compact, palisaded villages during this phase.

At the Hogue site, continuity between the Uwharrie and early Haw River ceramics can be seen. The most popular vessel form was a large undecorated, conical-shaped jar with a straight or slightly constricted neck. Most often the surfaces of these vessels were finished with a net-wrapped paddle. These vessels are ancestral to the Haw River series pottery of the latter half of the Haw River phase.

Most late Haw River phase settlements are small dispersed households. These are frequently found along ridges and knolls bordering narrow floodplains of secondary streams.

Typical pit features are fairly large cylindrical storage facilities. Evidence of agriculture, primarily maize, but also beans, squash, and sunflower seeds, has been found in all Haw River phase storage facilities. Additionally charred fragments of acorns and hickory nuts and animal bones are found. Although domesticated plants began to be an important food, wild resources continued to be used.

Dan River Phase (A.D. 1000 – 1450)

The Dan River phase emerged in the upper Dan River drainage of the Northern Piedmont at the same time as the Haw River phase of the Central Piedmont. A much larger population occupied the Dan River Valley during Late Woodland times than the Eno and Haw River drainages. After the 13th century Dan River phase people aggregated into substantial large villages.

Early Dan River sites were very similar to those of the Haw River phase, with linear communities of houses and associated features strung out parallel to the river bank.

Large storage pits contained a wide variety of plant and animal remains, while evidence of maize was recovered from almost every pit feature. Beans, sunflower seeds, and maize clearly indicate the importance of agriculture after A.D. 1000.

During the first half of the Dan River phase, Uwharrie influences are clearly evident. Most pots were formed into large storage and cooking vessels. Decorations consisted of notches along the lip, incised or brushed lines around the neck, or sometimes fingernail pinches or punctations in the neck area.

Most Dan River phase pottery is net-impressed. Large storage and cooking jars with constricted necks and flaring rims continued to be made along with smaller bowls. Vessel decoration increased in popularity from early to late Dan River sites. Finger pinches, stick incisions, and reed punctations were applied in bands around the shoulder area, while lips were commonly notched, incised, or punctated with reeds.

One of the most striking features of the Dan River phase is the variety of ornaments and tools made from bone, shell, and clay. Awls, pins, needles, fishhooks, beamers, gouges, antler flakers, antler picks, and turtle carapace bowls and cups, as well as a variety of beads, represent some of the bone artifacts. The edges of mussel shells were serrated and used as scrapers. Marine whelk shell was carved and ground into long and short beads, gorgets, and pendants. Marginella and olive shells were used to make beads. Clay was fashioned into cups, spoons, dippers, beads, and a variety of smoking pipes.

During the last half of the Dan River phase, settlement size and density increased dramatically. Many of these larger and more numerous settlements were located along the banks of the Smith and Mayo rivers in southern Virginia, as well as along the Dan River in North Carolina. Circular, stockaded villages from one to two acres in extent contained fifteen to twenty households with associated storage pits, hearths, and burials. These encircled open central plazas. Late Dan River phase villages were located on wide alluvial terraces of the Dan River and its major tributaries.

It seems likely that the rise of large fortified communities may be related to an increase of Iroquois raids from the north into the Eastern Siouan heartland.

Donnaha phase (A.D. 1000 – 1450)

The Donnaha phase is named for the Donnaha site, located in the Great Bend area of the Yadkin River Valley. Donnaha is a large, rich site that was occupied throughout most of the Late Woodland period. Related to the Dan River phase, Yadkin River valley Late Woodland sites are found on good agricultural soils westward to the Blue Ridge, where a blending of Late Woodland traditions from both the mountains and the Piedmont is found.

Hillsboro Phase (A.D. 1400 – 1600)

Hillsboro phase sites in the Central Piedmont follow the Haw River phase. Ceramic differences strongly suggest that the early Hillsboro phase population moved here from outside the area, much like Pee Dee in the Southern Piedmont.

Although small, scattered settlements similar to the Haw River phase continued to dot the landscape during the Hillsboro phase, a few sites dating to the first half of the phase represent compact, nucleated villages with relatively large populations. The best example of this kind of community is the Wall site/a> on the Eno River at Hillsborough.

The Wall site covers approximately 1.25 acres, of which one-fourth has been excavated. These excavations uncovered seven circular houses that average almost 35 feet in diameter. Two smaller “special purpose” structures that may have served as cribs or sheds have also been identified. Eight burials and seventy-three other pit features have been excavated. Five stockade alignments surround the ring of houses. The Wall site was probably occupied by a population of 100 to 150 people for less than twenty years in about the middle of the fifteenth century.

The mixed subsistence base that developed during the Haw River phase continued during the early Hillsboro phase. The rich bottomlands of the Eno were planted in fields of corn, beans, and squash, and wild plants and animals provided variety to the diet.

Although continuity can be seen between Haw River and Hillsboro phase subsistence practices, discontinuity characterizes the two ceramic assemblages. Only about 1.5 percent of the pottery from the Wall site displayed attributes characteristic of the Haw River phase. Instead, almost 75 percent of the Hillsboro phase pottery had simple-stamped surfaces. The remainder were check-stamped or plain, suggesting that early Hillsboro phase populations moved into the Eno valley from outside the area.

Simple stamped pottery typical of that at the Wall site was found alongside net-impressed and complicated stamped pottery at other late Hillsboro phase sites. Net-impressed sherds represented the last gasp of the ceramic tradition that began during the Uwharrie and Haw River phases. The complicated stamped sherds are similar to the Caraway series found at the Poole site in Randolph County, indicating increased contact with adjacent regions

Most of the Wall site burials were placed in what archaeologists call shaft-and-chamber pits, formed by digging a cylindrical shaft and then a tunnel-like chamber off to one side at the bottom. All the burials were oriented with their heads pointing in an eastward direction and usually located just within or just outside houses. Grave offerings consisted of small clay pots that probably contained food remains. Often shell beads were sewn on burial garments or strung as jewelry. Engraved shell gorgets were sometimes around the necks of children.

Late Hillsboro phase sites show more affinities to the earlier Haw River phase settlements. The resident population seems to have dispersed and there is no evidence of stockades. These later, more intensely occupied sites are found along narrow valley margins or adjacent uplands of small tributary streams.

Early Saratown Phase (A.D. 1450 – 1600)

Early Saratown sites in the North-Central Piedmont follow the Dan River phase and date to the period just before contacts with Europeans. These sites show signs of a stable population joined in fewer but larger villages. The phase was defined from excavations at the Hairston site (aka Early Upper Saratown), one of the most intensively occupied sites in the Dan River valley.

Early Saratown phase pottery has been described as the Oldtown series – a well-made ware with fine paste and smooth interiors. The majority of sherds have smooth or burnished surfaces, while others have net-impressed surfaces. Decorations include rim notching, finger pinching, and stick punctation similar to Dan River phase ceramics. New decorative techniques include rim castellations, lip burnishing, and the application of filleted strips. Vessel forms include bowls and jars. Influences from the Catwaba drainage to the south are present.

Burials at Hairston contained a rich array of grave goods, in stark contrast to the earlier Haw River and Dan River phases. Shaft-and-chamber burials were accompanied by the most offerings, including hundreds of bone and shell beads, bone awls, shell hair pins, serrated mussel shells, three “rattlesnake” or “Citico”-style gorgets, and a single pottery vessel. Contact with a copper bar gorget preserved a piece of pine bark covering one burial.

The majority of features at Hairston were large cylindrical or bell-shaped storage pits. Earth ovens, shallow basins, and hearths were also found.

Compared with the earlier Dan River phase remains, the Early Saratown phase had a much broader-based subsistence. A wide range of resources from a variety of habitats sustained Early Saratown people. The size and intensity of the Hairston site occupation suggest that the increased reliance on agriculture that began during the preceding Dan River phase reached its peak just before contact with the first Europeans.

The occupations of the Sara Indians in this area continued until after A.D. 1700 as the Middle Saratown and Late Saratown phases.

Close Piedmont

While Piedmont Woodland cultures were characterized by continuity and gradual internal change, the Woodland of the North Carolina mountains was a time of increasing cultural diversity stimulated by ideas from outside the region. Much of what is known about the Early and Middle Woodland periods in the Appalachian Summit is the result of research in eastern Tennessee.

Beginning in the 1960s, the University of North Carolina’s Cherokee project established the chronological and stylistic markers of the Woodland and research by the University of Tennessee at Knoxville filled in details of settlement, subsistence, and overall cultural change and adaptation.

Early Woodland – The Swannanoa Phase (1000 – 300 B.C.)

Early Woodland ceramics similar to the Piedmont Badin series are found in the Appalachian Summit. The Swannanoa pottery series has thick vessel walls (from 7 mm. to 22 mm.) with cordmarked and fabric-impressed surfaces. Check-stamped, simple stamped, and plain surfaces were added later in the phase. A few steatite vessel sherds suggest continuity with the preceding Late Archaic period.

Stylistically, Swannanoa pottery is similar to Kellog ceramics of North Georgia, Watts Bar pottery of eastern Tennessee, and Vinette wares of eastern New York state.

The Swannanoa phase is characterized by small, stemmed projectile points called Swannanoa Stemmed, Plott Stemmed, and Gypsy points. These represent the last gasp of the stemmed-point tradition that began at the close of the Late Archaic period.

Like other varieties of Early Woodland stemmed points, the Swannanoa phase points also were found stratigraphically associated with a large triangular point type named “Transylvania Triangular.”

Although several kinds of Swannanoa phase features were found at the Warren Wilson site, large hearth areas composed of clusters of fire-broken rock were most common. These stand in marked contrast to the relatively small, circular pit hearths of the preceding Late Archaic period. No cultigens or seed plants have yet been found in the small sample of subsistence remains known for Swannanoa phase. Rather, arboreal nut crops show continuity with Archaic economic pursuits.

Middle Woodland (300 B.C. – A.D. 800)

Current evidence suggests that Middle Woodland connections can be seen in areas outside the Appalachian Summit region. Two distinct phases of Middle Woodland occupation have been recognized: the Pigeon and Connestee phases.

Pigeon Phase (300 B.C. – A.D. 200)

Early in the Middle Woodland period ceramic connections are seen to the south, where carved wooden paddles were first used to stamp the surfaces of pottery vessels.

Connestee Phase (A.D. 200 – 800)

In spite of a clear developmental relationship with the Pigeon phase, the Connestee phase is distinctive. Exotic artifacts show connections with other Middle Woodland groups and indicate participation in the Hopewell interaction network. Later in the Connestee phase, southern influences from the Swift Creek area of southern and central Georgia continue to be felt after the Hopewell climax.

Middle Woodland pottery reflects a dramatic break with the cordmarked and fabric impressed ceramics of the Swannanoa phase. Vessel forms and surface treatments show continued change throughout the Woodland Period.

Large triangular points began during the Swannanoa phase and appear to be associated with the introduction of the bow and arrow. During the Middle Woodland period small sidenotched and triangular projectile points are found.

Late Woodland (A.D. 800 – 1100)

Cultural dynamics and stylistic markers of the Late Woodland period in the Appalachian Summit region are poorly understood. One excavated site that appears to have been occupied during this time is the Cane Creek site in Mitchell County.

The Cane Creek site had a remarkably homogenous ceramic assemblage with plain, smoothed, or brushed surfaces, and frequently notched vessel rims. None of the tetrapodal vessel supports of the preceding phases were found. Cane Creek’s well-preserved assemblage of bone tools and mortuary pattern are similar to Late Woodland cultures throughout the Southeast between A.D. 800 and 1200.

The cultural uniformity of Cane Creek site only heightens the seeming disparity between Woodland cultures and the Mississippian-influenced cultures that appeared abruptly after A.D. 1200.

Close Mountains

- Badin Crude Triangular spear points from the Doerschuk site in Montgomery Co., NC

- Randolph Stemmed and Caraway arrow points from the Doerschuk site in Montgomery Co., NC

- Yadkin Large Triangular spear points from the Doerschuk site in Montgomery Co., NC

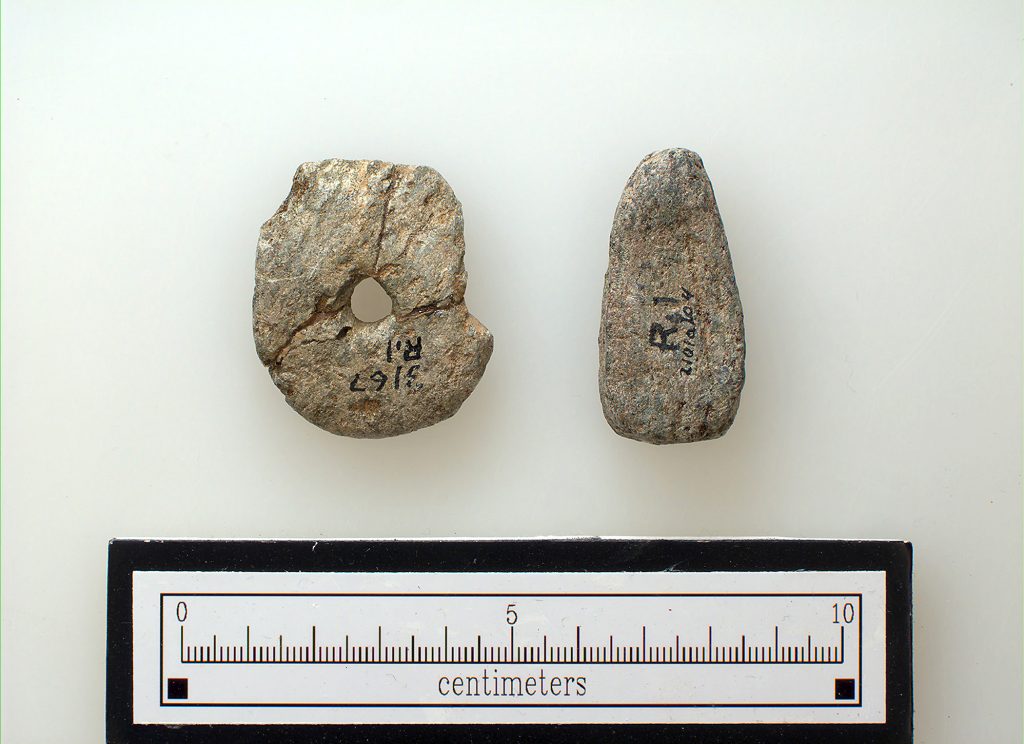

- Stone gorget fragments from the Leak site in Richmond Co., NC

- Soapstone objects from the Leak site in Richmond Co., NC

- Chipped-stone spear and arrow points from Richmond Co., NC

- Chipped-stone spear and arrow points from Stokes Ferry in Stanly Co., NC

- Chipped-stone spear and arrow points from Stokes Ferry in Stanly Co., NC

- Chipped-stone spear and arrow points from Badin Lake in Stanly Co., NC

- Chipped-stone drills from the Hardaway site in Stanly Co., NC

- Chipped-stone spear and arrow points from the Hardaway site in Stanly Co., NC

- Chipped-stone spear and arrow points from the Lowder’s Ferry site in Stanly Co., NC