Paleoindian (14000–8000 B.C.)

The Paleoindian is the time of the earliest generally accepted arrival of people in the southeastern United States – about 16000 years ago, or 14000 B.C. Although earlier migrations of people into the New World have been hypothesized, currently there is no firm evidence of people anywhere on the continental United States prior to 14000 B.C.

Our level of understanding of the Paleoindian period across the state is highly uneven, due to both the history of North Carolina archaeology and environmental and geological factors.

Archaeologists working in the Southeast use radiocarbon dating and differences in spear point forms and frequencies to tell time during the Paleoindian. Questions regarding settlement and subsistence can be addressed by studying the frequencies and distribution of the various types of spear points.

Paleoindian in the Southeast is divided into Early, Middle, and Late periods. Spear points of the Early Paleoindian period (14000 – 9000 B.C.) are large, fluted lanceolates, very similar to the classic Clovis points of the West. What we know about the earliest inhabitants of North Carolina is based almost entirely on surface finds of these points. Concentrations of Early Paleoindian points have been noted in the Tennessee, Cumberland, and Ohio River valleys, as well as western South Carolina, southern Virginia, and the northern Piedmont of North Carolina.

In the Middle Paleoindian period (9000 – 8500 B.C.) the number of spear points increases considerably and regional differences in point forms emerge. The Cumberland, Suwanee, and Simpson point types are thought to be typical of this Middle period. One thing all have in common is a narrowing, or “waisting,” at the base.

The Late Paleoindian period (8500 – 7900 B.C.) shows increased population growth. Dalton points are the diagnostic type for this time period. By the end of the Paleoindian, Holocene climatic conditions prevailed and the basic hunting and gathering lifeway that persisted for the next 5000 years was set.

Close Chronology

The earliest settlers in the Southeast arrived around 16,000 years ago and found a rapidly changing landscape. Current evidence suggests that many of extinctions of large Pleistocene mammals – including the horse, mastodon, and mammoth – were complete by 8500 B.C.

East of the Mississippi River almost no Paleoindian tools have been found with these animals. Environmental differences between the Eastern and Western parts of the continent may have necessitated very different adaptations. By the Middle Paleoindian period, if not earlier, the subsistence pattern was probably very similar to that of the Early Archaic period.

Most southeastern Paleoindian sites where more than a single point has been found are related to stone-quarrying activities. This pattern reflects a generalized foraging strategy where groups rarely engaged in food-getting activities that produced recognizable traces in the archaeological record.

Close Settlement and Subsistence

The Coastal Plain

Ocean levels were lowered by 150 feet or more during the last glacial period. This means that during Paleoindian times the coast was 230 to 300 miles from the Piedmont. Today, the Paleoindian sites from before 10,000 ago near the coast lie submerged; Paleoindian sites found near today’s coast represent adaptations to what was then the central Coastal Plain.

The Coastal Plain probably had hardwood forests dominated by beech and hickory. The climate was cooler and wetter than North Carolina today, and may have been very similar to the modern climate of New York.

Paleoindian points have been found only sporadically in the Coast and Coastal Plain, with less than fifty sites known. In part this is because the region has not been surveyed as extensively as other regions of North Carolina.

The Piedmont

During the full glacial period (17000 – 14500 B.C.) when Paleoindians first arrived, the Piedmont was a boreal forest, containing pines, spruces, and larches. As temperatures warmed, conifers were replaced by deciduous forests (oak, hickory, walnut, elm, willow, and sugar maple) by 10500 B.C. Continued warming brought new forests of sweet gum, chestnut, red maple, and tupelo gum by 7000 B.C. When Paleoindians first came into the Piedmont, winters were harsher and summers cooler than today. For several thousand years, both people and now-extinct Pleistocene animals co-existed in North Carolina.

Hardaway is the most recognizable site name in North Carolina. Most stone tools found in the Piedmont are made from a fine-grained rhyolite that outcrops in the Uwharrie Mountains. Excavations at the Hardaway site in Stanly County have yielded tons of rhyolite tools and chipping debris dating to the Late Paleoindian and Early Archaic periods. The site was first recognized as important in the 1930s and excavations began after World War II.

The oldest component at Hardaway was represented by Hardaway-Dalton points, Hardaway Side Notched points, and Hardaway Blades, which date from 8500 to 7900 B.C. Other stone tools associated with the Hardaway complex, such as unifacial end scrapers and side scrapers, are very similar to those used by Paleoindians. In the Piedmont, roaming bands of hunter-gatherer Paleoindians probably enjoyed a wealth of natural resources that were exploited seasonally.

The North Carolina Mountains

Only a few Paleoindians sites have been found in the North Carolina mountains, and no buried, stratified sites have been found. As a result, little can be said about subsistence and settlement patterns in the Appalachian Summit area during Paleoindian times. Boreal forests comprised of spruce and fir probably persisted in the higher elevations of the southern Appalachian Summit throughout Paleoindian times. Now-extinct Pleistocene animals probably persisted later in the mountains than they did in other regions.

Close Regional Evidence

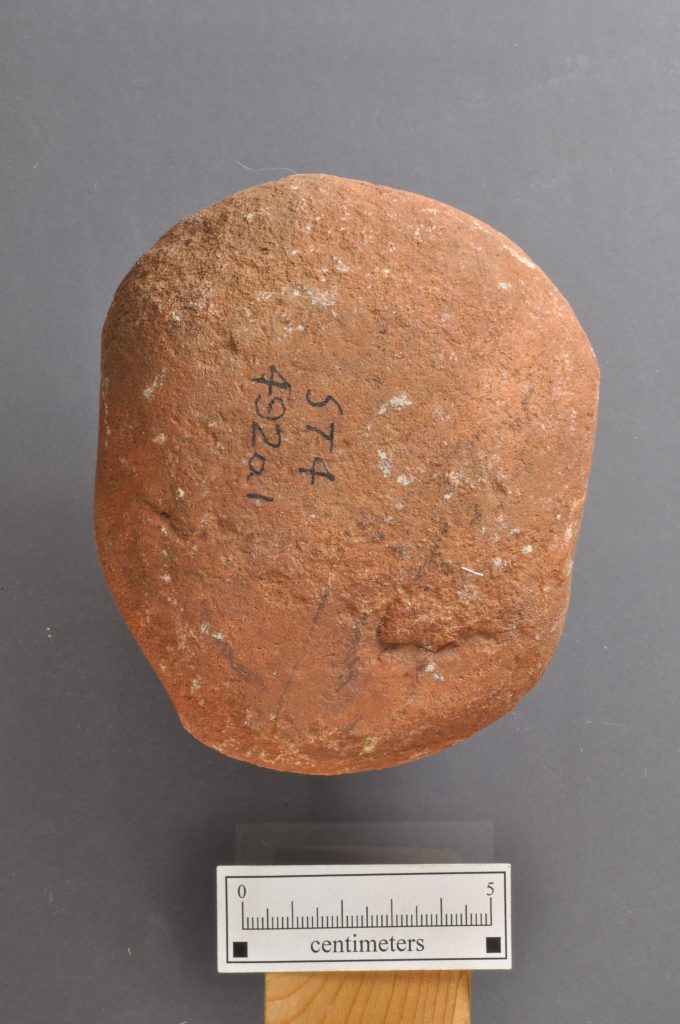

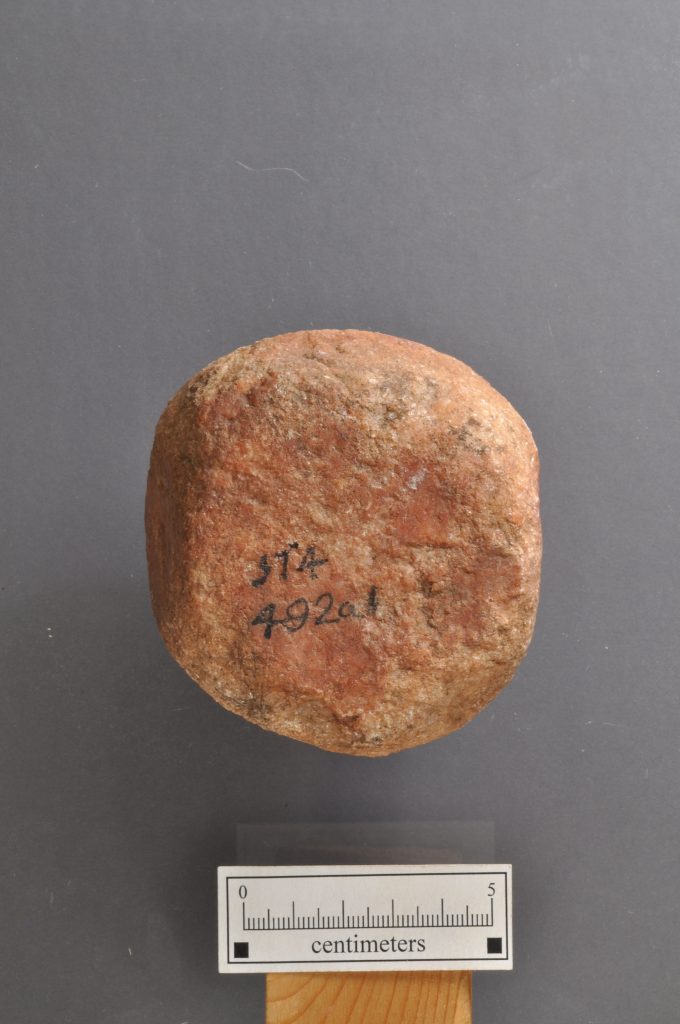

- Hammerstone from the Hardaway site in Stanly Co., NC

- Hammerstone from the Hardaway site in Stanly Co., NC

- Hammerstone from the Hardaway site in Stanly Co., NC

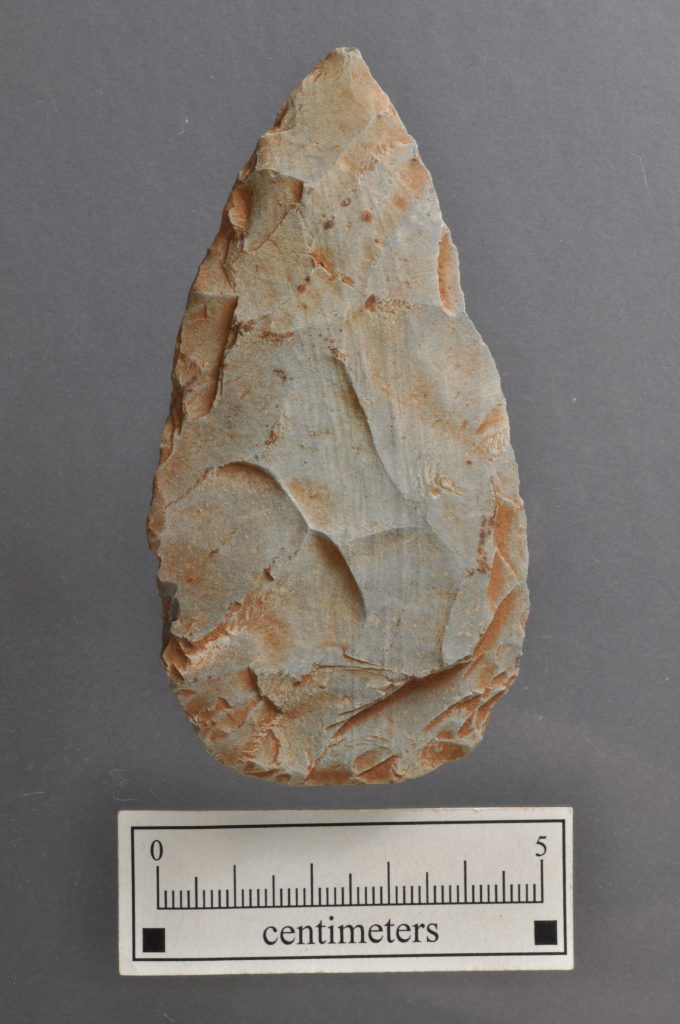

- Chipped-stone biface from the Hardaway site in Stanly Co., NC

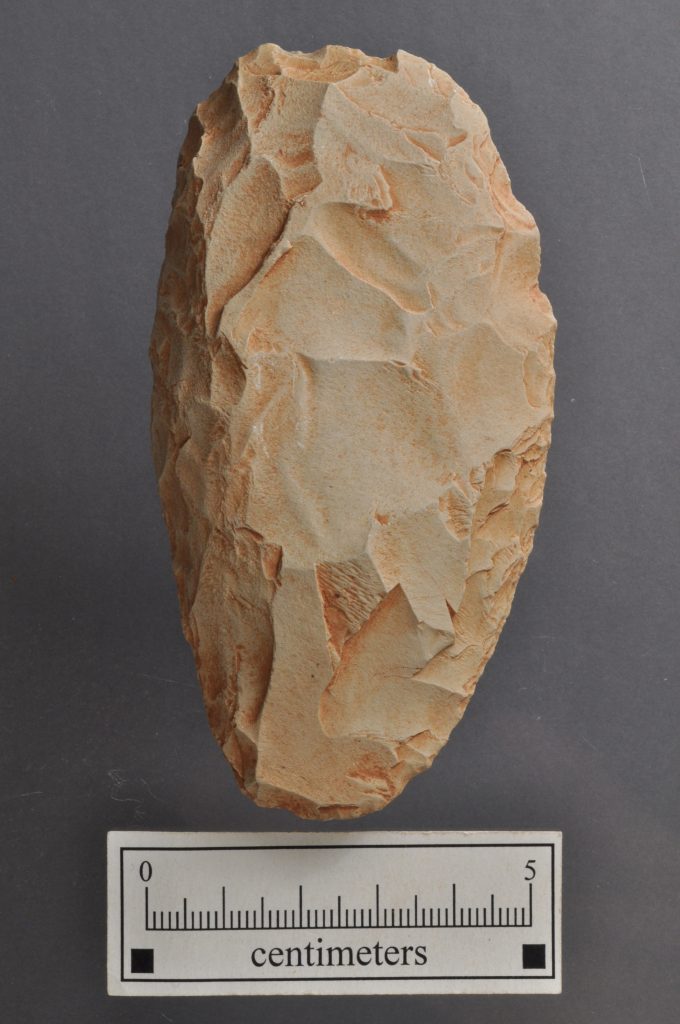

- Chipped-stone side scraper from the Hardaway site in Stanly Co., NC

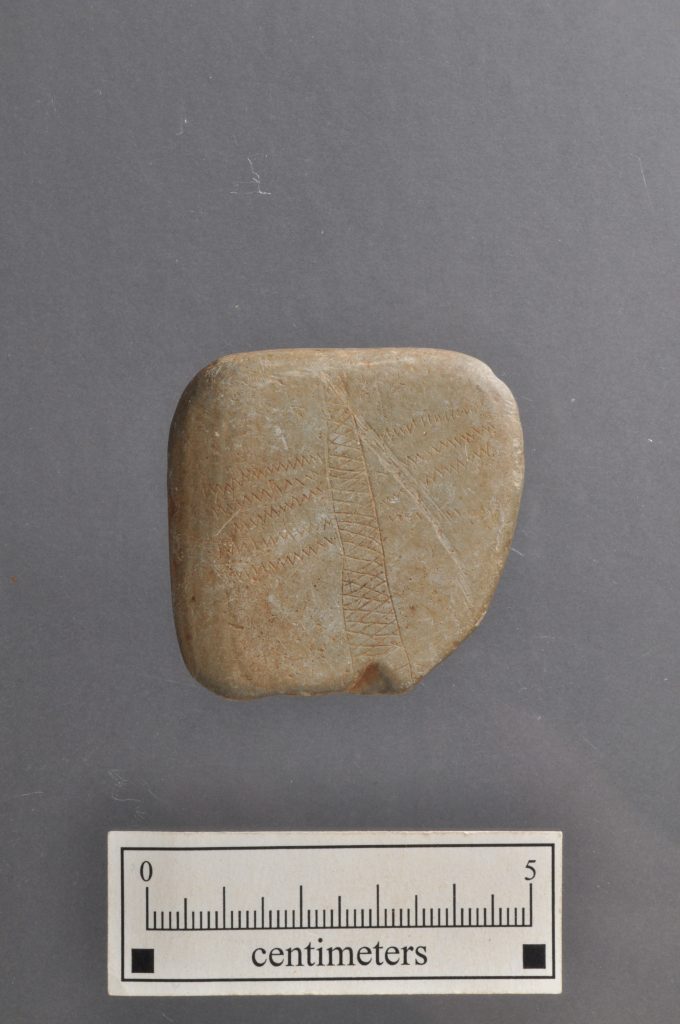

- Engraved pebble pendant from the Hardaway site in Stanly Co., NC

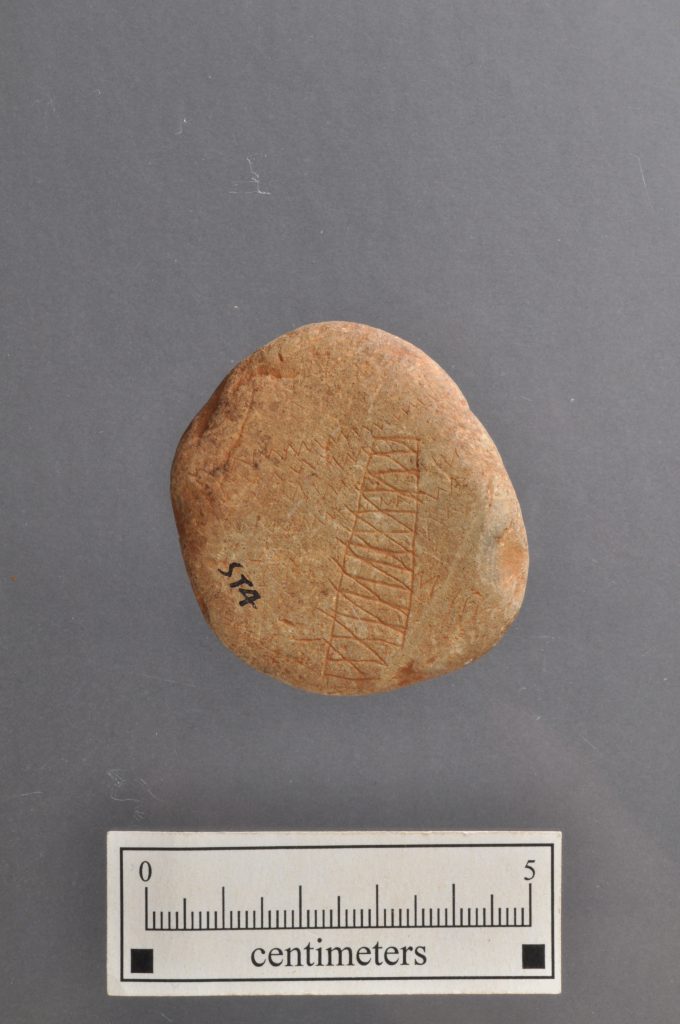

- Engraved pebble from the Hardaway site in Stanly Co., NC

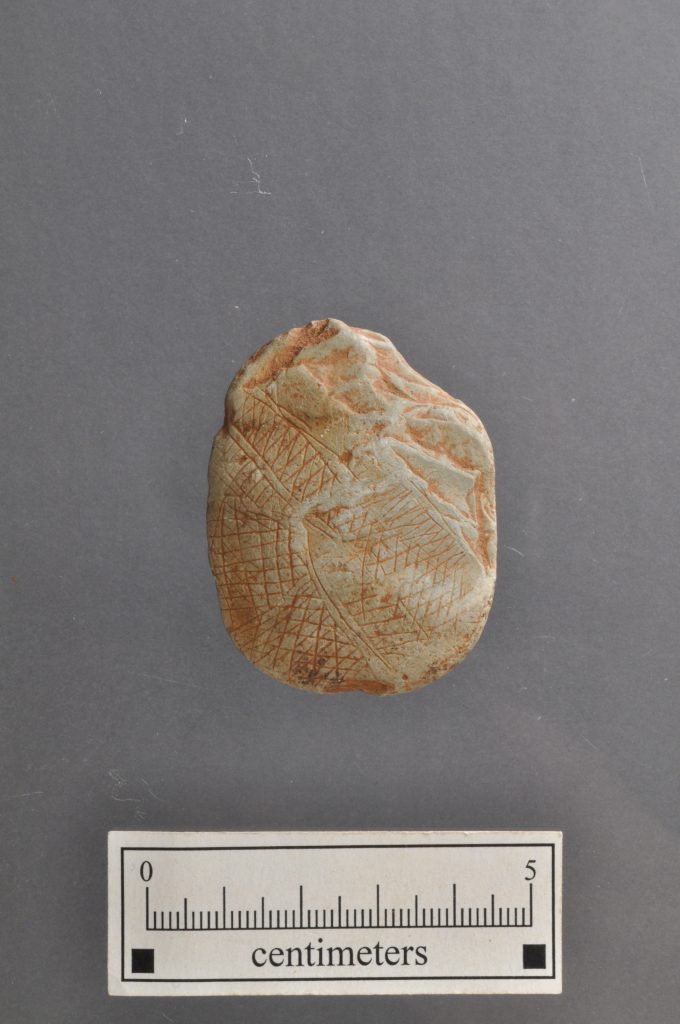

- Engraved pebble from the Hardaway site in Stanly Co., NC

- Engraved pebble from the Hardaway site in Stanly Co., NC

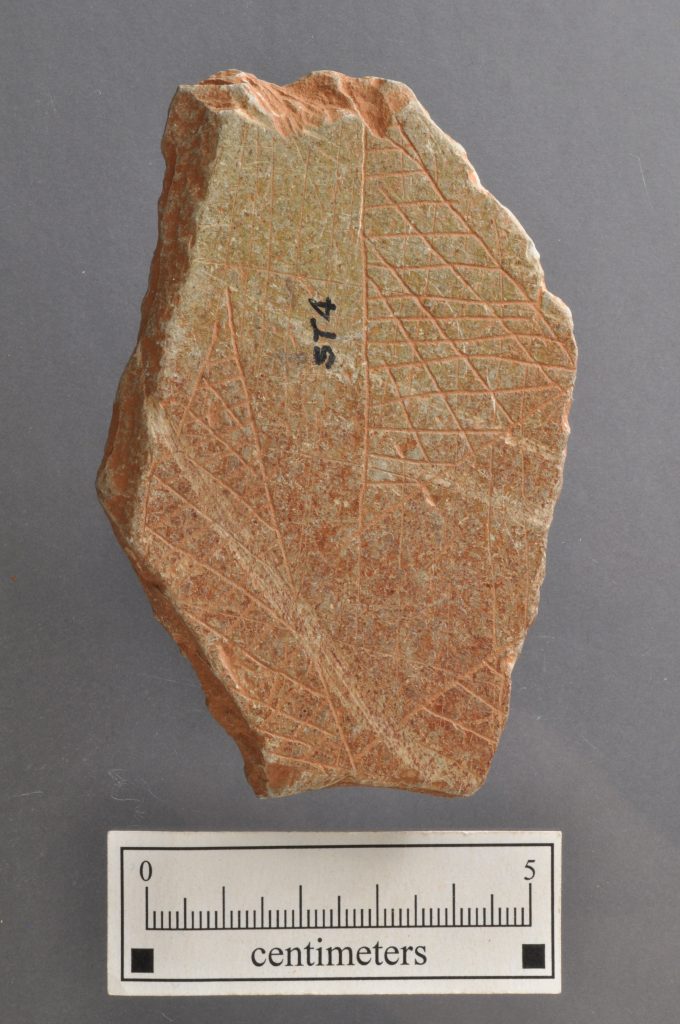

- Engraved slate from the Hardaway site in Stanly Co., NC

- Fluted spear point in a private collection from Burke Co., NC

- Fluted spear point in a private collection from Burke Co., NC