Town Creek (Mississippian)

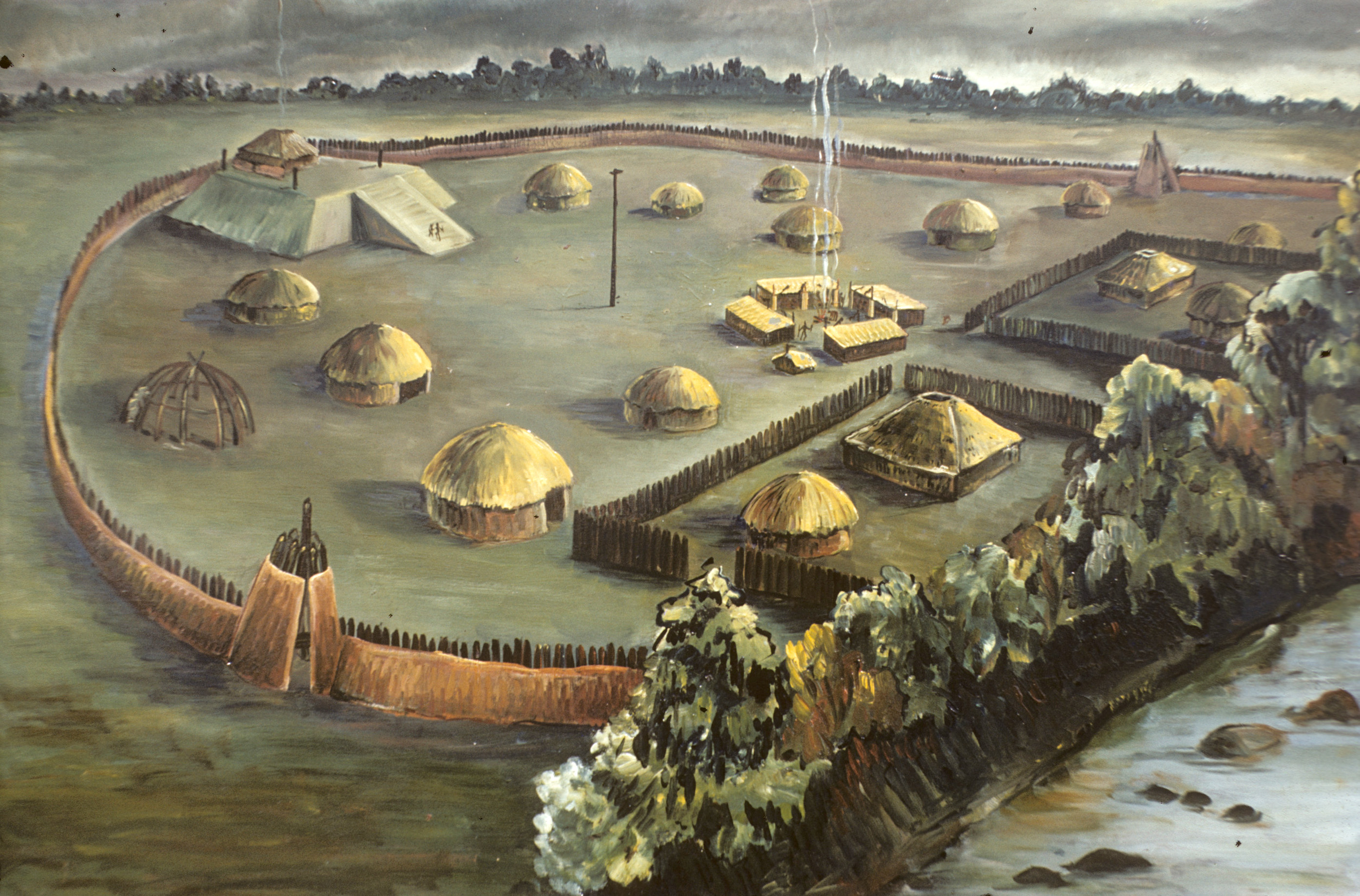

Town Creek (31MG2) has been a North Carolina State Historic Site since 1955 and is one of the most visited archaeological sites in North Carolina. It is located on the Little River, about 8 miles (9 km) north of its confluence with the Pee Dee River, near the current town of Mt. Gilead. Town Creek itself is located on a terrace about 16 feet (5 meters) above the surrounding floodplain. Although this area was used from the Paleoindian period to colonial times, it is most well-known for its intensive Mississippian occupation. This occupation is evidence by an 11-ft (3.5 meter) tall platform mound that was built in multiple stages, as well as thousands of postholes and pits between the mound and the Little River. The site probably functioned as a civic-ceremonial center, as it is the largest Mississippian site in the area and the only one with an earthen platform mound. The Mississippian component of the site is part of a cultural unit known as South Appalachian Mississippian, which is a regional variant of the larger Mississippian culture. The most visible characteristic of this Mississippian variant is the use of carved-paddle-stamped pottery that is tempered with grit rather than crushed shell. Within South Appalachian Mississippian, Town Creek is part of the Pee Dee cultural unit, an even more localized archaeological culture found in areas of south-central North Carolina and northeastern South Carolina.

History of Excavations

Much of the archaeological work at Town Creek was led by Joffre Coe, who was one of the early pioneers of Southeastern archaeology. The site was excavated from 1937 to 1984, with a seven-year break during and immediately after World War II. Through these and other excavations, almost the entire mound was been excavated along with over 96,000 square meters of the adjacent village. These excavations have uncovered an impressive 15,000+ archaeological features, more than 40 structures, and over 200 burials with nearly 250 individuals. During the Great Depression, the excavations were federally funded and the focus was on the mound and village area adjacent to the Little River. In the period from 1950 to 1984, small crews of 2-3 people worked year round excavating most of the rest of the village plaza and nearby domestic areas.

Research at Town Creek

Although Town Creek looms large in North Carolina archaeology, at the time of its occupation it would have been a relatively small community on the edge of the Mississippian world. As one of the most extensively excavated sites in the Southeast, however, Town Creek is extremely important for the information it can provide about an overall Mississippian community. More recently, archaeologists have undertaken new studies of the collections from Town Creek, leading to publications about the ceramics, burials and associated mortuary goods, and the architectural remains.

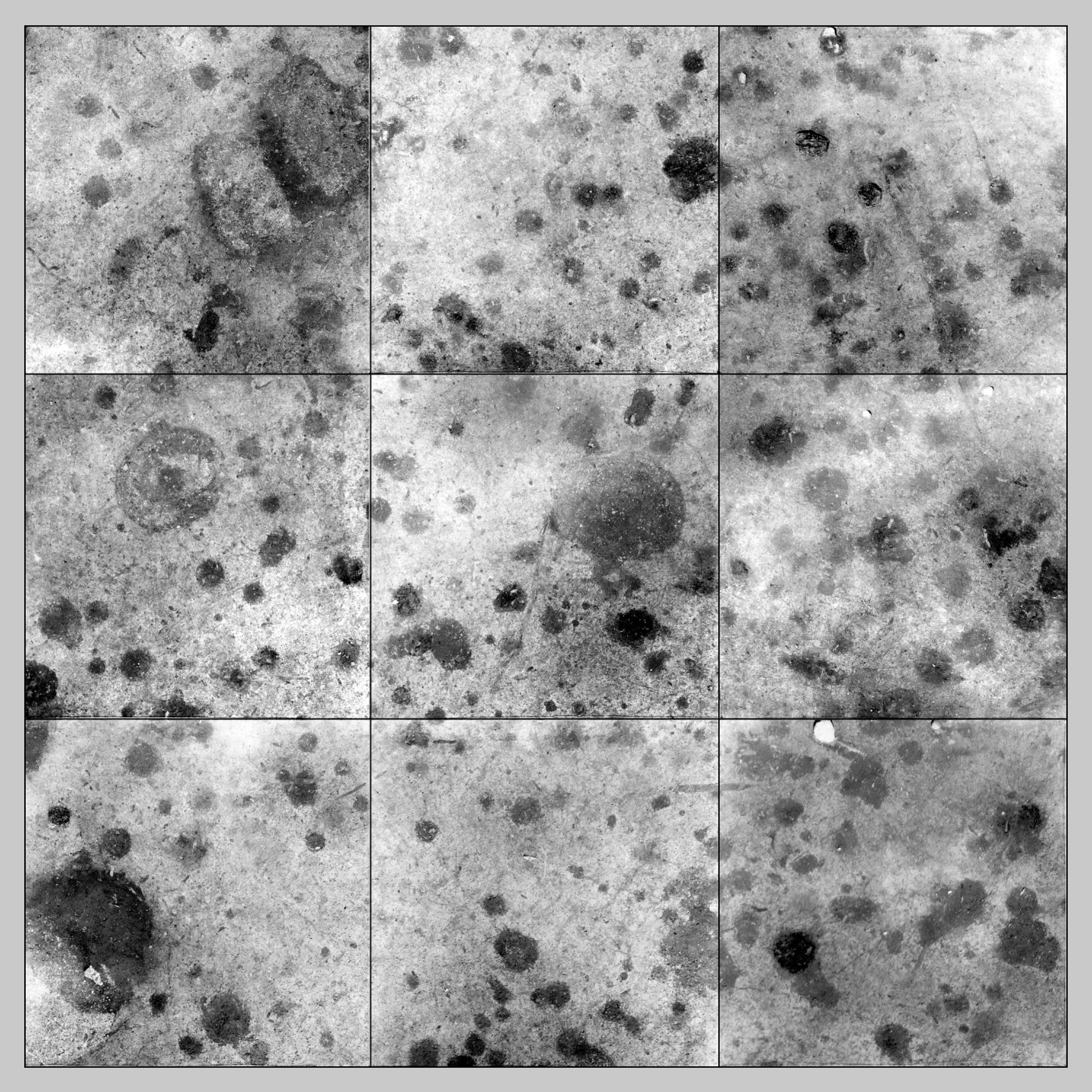

With the extensive use of Town Creek, it has been very difficult to make much sense of the large numbers of postholes and features at the site. In 2002, Steve Davis of the RLA and Tony Boudreaux, now at the University of Mississippi, put together a digital mosaic of the excavation photographs from Coe’s fieldwork. Doing so allowed Boudreaux to find patterns in the data, leading him to identify a number of individual and different types of structures, two enclosures, and several palisade lines. With these architectural patterns identified, Boudreaux was then able to look at the way that associated archaeological features overlapped, their spatial arrangements, and associated ceramics and radiocarbon dates to subdivide the Mississippian occupation into early and late phases. This new perspective has provided a window into how the use of the site by Mississippian people changed over time.

During the early Town Creek phase (A.D. 1150-1250) the site started out as a village of circular houses around a plaza. At about A.D. 1250, the platform mound was built. Then, during the early Leak phase (A.D. 1300-1400) the space around the plaza became home to kin-group cemeteries and associated structures. The burial patterns at Town Creek also reflect the changes that occurred between the early and late Town Creek communities. The human remains from Town Creek consist of 217 burials containing 249 individuals, with an estimated total of more than 500 burials at the site. These were systematically analyzed as part of the site’s Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) inventory. Early political power within the community was probably spread out among many individuals and multiple social groups. These groups are represented by adult women and men buried in public buildings and in one of the excavated houses. The fact that both sexes are represented suggests that both men and women participated in political processes and shared leadership roles. It is also possible that some of the political power of women was based on their roles as clan or lineage leaders.

During the late occupation phase at Town Creek, burial patterns changed; this is also when the mound was built. One striking change is that mound-summit burials and public buildings became places where young adults were buried. It may be that the status of a community leader was not one that was held throughout life and therefore the young adults buried in the mound-summit may represent a number of people who held the title of community leader at the time that they died. The age profiles and artifacts found on the mound summit also fit the idea that buildings atop and beneath the mound were not domestic houses, but instead were public buildings. Burials from this time period also contain new artifact types (e.g., rattles, mica, and ochre) that suggest the people buried in public spaces had new social and political roles, perhaps involving more prominent ritual roles that would have been associated with more political authority. Overall, the evidence at Town Creek suggests that later in time, one of the primary functions of the site changed to emphasize public rituals and community integration.

Town Creek is a great example of the importance of archaeological records and collections. Because these materials were carefully archived, researchers have been able to come back to Town Creek to learn much more than we initially knew. As archaeologists continue to revisit these collections, we will learn even more about what the Mississippian world looked like at its periphery in North Carolina.

Sources

Boudreaux, Edmond A.

2013 • Community and Ritual within the Mississippian Center at Town Creek. American Antiquity 78(3):483-501.

Boudreaux, Edmond A.

2011 • The Current State of Town Creek Research: What Have We Learned after the First 75 Years? In The Archaeology of North Carolina: Three Archaeological Symposia, edited by Charles R. Ewen, Thomas R. Whyte, and R.P. Stephen Davis Jr., pp. 1831-18.23. Publication Number 30. North Carolina Archaeological Council, Raleigh.

Boudreaux, Edmond A.

2010 • Mound Construction and Change in the Mississippian Community at Town Creek. In Mississippian Mortuary Practices: Beyond Hierarchy and the Representationist Perspective, edited by Robert C. Mainfort and Lynne P. Sullivan, pp.195-233. University Press of Florida, Jacksonville.

Boudreaux, Edmond A.

2007 • The Archaeology of Town Creek. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

Coe, Joffre L.

1995 • Town Creek Indian Mound: A Native American Legacy. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.

Ward, Trawick H., and R. P. Stephen Davis, Jr.

1999 • Time Before History: The Archaeology of North Carolina. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.