Historic (c. A.D. 1540–c. 1850)

The historic era in North Carolina covers the time of earliest contact between Indians and Europeans through to the present. In North Carolina, we split the Historic era into three periods: Early Contact, Colonial, and Federal. As a result of warfare and disease, however, most North Carolina historic Indian sites are related to early Contact and the Colonial period. For some sites, attempting to split them apart into Indian Heritage and Colonial Heritage is somewhat arbitrary; what we are aiming to emphasize through such categories on this site are which group the story of an archaeological site focuses on. Therefore, for some sites like Berry, you may see them listed twice, with a different emphasis in text.

Currently, the detailed overview for the Historic Era is focused on early contact; we are working to update this to include the Colonial and Federal periods.

The time of contact between Indians living in North Carolina and Europeans arriving from Spain and England varied considerably across the state. The expedition of Hernando de Soto passed through western North Carolina in the spring of 1540. Pardo’s expeditions into the same areas came less than 30 years later. The first English attempts at settlement in northeastern North Carolina came about 20 years after that, starting in 1584. But it was not until after about 1650, when English explorers, traders, and settlers came from Tidewater Virginia, that North Carolina’s Indians felt the brunt of the European presence on their land.

Accordingly, the beginnings of these arrivals do not necessarily herald the beginnings of significant changes in the histories of North Carolina’s tribes. Overall, however, this was a time of sweeping and often devastating change.

The archaeology of the Contact Period in North Carolina’s coastal regions is strongly supplemented by early English exploration and settlement which began here in the late 1500s. As in the Piedmont, contact period archaeology near the coast involves terminal Late Woodland societies entering into trade and political relationships with Europeans.

Following the failed late 16th-century attempt by Sir Walter Raleigh to colonize the North Carolina coast, the successful settlement at Jamestown in Virginia in 1607 gave the English the toehold they needed to expand. However, even with the successful founding of Jamestown, North Carolina’s Indians were given a fifty-year respite before having to deal with Europeans again.

Around 1650, Virginia settlers began to push southward along the coast, starting with the Albemarle region. For the most part, settlers did not venture very far inland at first. Instead they spread southward and stayed near the coast. By 1675 the southern shore of Albemarle was settled, and by 1691 newcomers were settling along Pamlico River. Soon after the beginning of the 18th-century the area of the Neuse River was settled.

Land-grabbing by aggressive colonists and the disruptions caused by the illegal, but lively, trade in Indian slaves that had sprung up after the founding of Charles Town in South Carolina, soon caused an unbearable state of relations between the colonists and tribes and lead to the Tuscarora War, in which two thousand Tuscarora were killed or sold into slavery. Many of the remnants of the tribe moved to Pennsylvania and New York.

In coastal regions archaeology is just beginning to supplement early historic accounts. An Algonkian village thought to be Croaton has been excavated on Hatteras Island. Amity, a mid-17th century village near Lake Mattamuskeet in Hyde County, has been excavated, and work has been done on historic Tuscarora communities and forts. However, there is a great deal yet to discover about the archaeology of the Contact era along the coast.

What is apparent is that pottery-making, subsistence, and patterns of settlement seem to have changed little during the first part of the Contact era along the coast. Ceramics similar to those of the Cashie, Colington, and White Oak/Oak Island phases continued to be made. Longhouses were still used and a mixed economy based on hunting, gathering, fishing, shell-fish, and agriculture continued. However, aboriginal life was rapidly disrupted as outsiders moved in. By 1701 John Lawson was able to observe that the coastal tribes were “very much decreased.”

Close Contact along the Coast

Between 1936 and 1941 the University of North Carolina’s first Siouan Project searched the Piedmont hoping to locate and identify historic Siouan villages described in the 17th and 18th century. Results were inconclusive. A return to this research four decades later, under UNC’s second Siouan Project, had much better success in exploring the question of what happened to the state’s native inhabitants as European explorers, traders, and settlers moved into the North Carolina backcountry during the last half of the seventeenth century and early eighteenth century. This success finding historically documented villages in the north central Piedmont has allowed development of a detailed cultural chronology allowing archaeologists to study processes of cultural change during the Contact era.

Trade

In the timespan from A.D. 1600 to 1670, only a few glass and brass/copper beads found their way into Piedmont villages. These items were exchanged through native intermediaries operating traditional trade networks. During the 1670s, however, trade changed dramatically as Virginia traders began making regular trips into the backcountry searching for new markets.

The intensification and spread of the peltry trade is directly reflected at sites of the 1670 to 1710 period (the Late Saratown and Fredricks phases). Literally thousands of beads and other ornaments, but few tools and weapons, moved into the Sara sites on the upper Dan River, while guns, knives, hatchets, beads, and trinkets were obtained in quantity by the central Piedmont Occaneechi, who controlled the flow of goods to the more remote Sara. After 1680, with the Occaneechi stranglehold broken, the Sara gained access to weapons and other tools.

European tools and ornaments were used alongside of their counterparts made with traditional technologies, rather than replacing them. Despite this shared use, the flow of goods had a great impact on social structure. Whereas authority and prestige had been accorded primarily to women in the earlier seventeenth century, men’s routes to status were enhanced when trade in European goods greatly increased.

Intertribal Relations

Intertribal conflict and warfare certainly preceded the arrival of Europeans. However, hostilities increased dramatically when Indian slaves and deerskins could be traded for the kettles and guns of the Europeans. Bones scarred by scalping and bullets are clear evidence of these hostilities. Conflicts often took the form of raids from as far away as New York and Pennsylvania.

Whereas in the past blood feuds and revenge fueled the fires of conflict, new motives and new ways of conducting warfare were introduced. Unprecedented opportunities to exert economic and political power were available by controlling the flow of trade and acquiring weapons.

Subsistence

Archaeological evidence has shown that the new plants and animals brought by Europeans were virtually ignored by most Piedmont Indians during the Contact Period. Peaches and watermelons were widely planted, often reaching native communities well in advance of the Europeans themselves, but the traditional trinity of native crops (corn, beans, and squash) remained the mainstay. Likewise Old World animals were seldom raised.

As was the case with tools and trinkets, only those items that did not require a re-organization of the traditional ways of doing things were incorporated, and these were used alongside of, not in place of, familiar resources.

Disease

Without a doubt, the most devastating result of the European arrival into the North Carolina Piedmont was the introduction of new diseases for which the native populations had little or no resistance. Smallpox, measles, and other viral diseases swept the region, killing and disabling thousands. This devastation was accelerated during the late 1600s by increased population movements and expanded intertribal contact as native people adapted to the economic and political changes brought about by the trade.

Spread of Old World diseases depended on a number of local and regional factors. Population density, community size, and degree of contacts all affected the timing, speed, and scope of disease events.

In the north central Piedmont, there is no evidence of epidemic diseases until the arrival of Virginia traders in the second half of the seventeenth century. Only in the Late Saratown and Fredricks phases is there evidence of diseases in the form of dramatic increases in the numbers of graves and changes in burial practices.

Close Contact in the Piedmont

In the latter half of the seventeenth century, North Carolina’s Indians felt the brunt of the European presence in their land. The initial advance of Europeans into the backcountry of North Carolina came from Tidewater Virginia, not coastal North Carolina. In the central Piedmont, a series of sites have been excavated from this time period illustrating the effects of these contacts.

Starting in 1983, the University of North Carolina’s second Siouan Project succeeded in finding sites of the Siouan tribes who interacted with the European explorers, traders, and settlers who moved into the North Carolina backcountry during the last half of the seventeenth century and early eighteenth century.

In the Central Piedmont three phases provide a detailed chronology of changes during the Contact period.

The Mitchum Phase (A.D. 1600 – 1670)

The Mitchum phase is known from a single site located in Chatham county adjacent to the Haw River. The phase is attributed to the Sissipahaw Indians in the early part of the 17th-century. Trade artifacts at Mitchum indicate that the site was occupied around 1650 and abandoned before John Lawson visited this location in 1701.

The Mitchum site was a small stockaded village of less than 1.5 acres. The only house found was oval with posts set in individual holes. It was probably covered in bark or skins. Storage pits, smudge pits, hearths, and two graves were found. Glass beads and brass ornaments, obtained through indirect trade with the English, were place with the dead.

Pottery of the Mitchum phase developed out of the preceding Hillsboro phase and is very similar to the pottery of the contemporary Jenrette site on the Eno River. Subsistence practices changed little as a consequence of contact with Europeans. Peach pits provide the only evidence of European influence on the Mitchum phase diet.

Milder forms of non-native tobacco, perhaps from the West Indies, may have been an important commodity in the trade network with the English. Finely made clay pipes resembling English kaolin pipes begin showing up in relatively large numbers on sites from this time, suggesting a change in smoking behavior after 1650.

European trade items were obtained in limited number and variety through indirect trade. A few gunflints, but no firearm parts were found. Knives, hatchets, hoes, and other iron tools apparently were not available. The trade inventory consisted mainly of ornaments.

The Jenrette Phase (A.D. 1600 – 1680)

The Jenrette Phase is also defined by information from a single archaeological site. Jenrette site is located near Hillsborough along the Eno River, right next to the Fredricks site and near the Wall and Hogue sites. Jenrette may be the remains of a Shakori Indian village visited by John Lederer in 1670.

Jenrette’s stockaded village covered one-half acre, with an open central plaza. Due to plowing, only two of the numerous houses which originally surrounded the plaza were clearly identified by remaining wall patterns. A small number of burials in the village area suggests that European diseases had not yet affected the Eno River population.

Unlike most houses found on sites in the Piedmont, the Jenrette structures were built by placing wall posts in long trenches rather than individual post homes. Wall trenches were also used at the slightly later Fredricks site.

Most of the Jenrette features were storage pits and large food preparation facilities identified as roasting pits or earth ovens. Large shallow roasting pits like the “feasting pits” described for the late Hillsboro Phase were usually located near the stockade.

The ceramic assemblage from the Jenrette site is very similar to the Mitchum Phase. Both comprise the Jenrette ceramic series. However, it is believed that the Jenrette pottery was made by Shakori, not Sissipahaw, potters. Although similar to the ancestral Hillsboro series, Jenrette series vessels are heavier, have thicker walls, and are more crudely made.

Small triangular arrowpoints, as well as other stone tools (drills, perforators, gravers, spokeshaves, and scrapers, as well as groundstone celts, chipped-stone hoes, and milling stones) continue to be used during Jenrette phase. Bone and shell tools also persist and resemble the preceding Hillsboro Phase. These traditional tools were soon to be replaced in the ensuing Fredricks Phase.

Subsistence remains at Jenrette are very similar to samples from sites occupied just prior to European contact. No significant changes in practices or diet can be seen. White-tailed deer, fish, acorns, hickory nuts, and walnuts were important wild foods, while corn, beans, bottle gourds, and sumpweed were cultivated. Peaches were the only non-native food harvested.

The inhabitants of Jenrette buried their dead in both shaft-and-chamber and simple straight-sided pits. Associated artifacts (primarily small glass beads sewn on garments) reflect the beginnings of trade with the English. There is a lack of epidemic diseases during the Jenrette phase.

The increased popularity of pipe smoking seen in the Mitchum Phase is also seen in Jenrette Phase. Numerous terracotta pipes were used alongside traditional forms. Fine rouletted designs, like those decorations found on “Tidewater” pipes throughout the Middle Atlantic region, are seen on Jenrette terracotta pipes. This style of pipe is also found on sites dating to the Middle Saratown, Late Saratown, and Fredricks Phases and provide an excellent horizon marker for the 1650 to 1700 period.

The Fredricks Phase (A.D. 1680 – 1710)

The Fredricks phase is named for the Fredricks site, which is located along the Eno River near Hillsborough and appears to be the remains of Occaneechi Town. This was the home of the Occaneechis after they moved from the Roanoke valley in 1676. The town was visited by John Lawson in 1701.

This small stockaded village of no more than ten or twelve houses was completely excavated between 1983 and 1986. Probably fewer than seventy-five individuals lived in the village for less than a decade, but three separate cemeteries were found here. The small size of the settlement and the many graves indicates a very high mortality rate. The separate cemeteries may indicate different ethnic groups were being forced to band together as a result of depopulation.

Trade between the Piedmont Indians and the English intensified during the last quarter of the 17th century. Grave goods left with the Occaneechi burials include knives, tobacco pipes, hoes, kettles, and guns, as well as the beads and ornaments that had been common during the earlier Contact Phases. Graves were no longer placed in and around dwellings and were dug with metal tools. Perhaps partially as a consequence of this technological change, traditional shaft-and-chamber graves were replaced with rectangular, straight-sided graves aligned in three cemeteries outside the stockade.

Fredricks Phase pottery is more closely related to Hillsboro series pottery than the Jenrette series. Two pottery types are present at Fredricks; Fredricks Plain is associated with a variety of vessel forms, while Fredricks Check Stamped is almost exclusively cooking vessels. The homogeneity of the Fredricks series suggests that all the pottery was made by one or two potters.

Although the Fredricks Phase represents a time of dramatic disruption, a surprising degree of continuity is reflected in the subsistence data. The peltry trade and the introduction of European tools and trinkets seems to have had only minimal impact on the day-to-day subsistence of the Occaneechis. Only one bone each of a horse and a pig attest to the European presence and the only European plants are watermelon and peaches.

Stone tools continued to be used alongside European-made weapons and cutting tools. The Occaneechis do not appear to have been heavily engaged in working bone or shell. The shell ornaments recovered, including gorgets, columella beads, disk beads, wampum, and runtees, were probably manufactured by groups along the Atlantic Ocean.

Close Contact in the Central Piedmont

In the North-Central Piedmont, two Contact-era phases of the Sara (or Saura) tribe follow the Early Saratown phase and provide a chronology of changes.

Middle Saratown Phase (A.D. 1620 – 1670)

The Middle Saratown phase represents the mid-17th-century occupation of the upper Dan River drainage by the Sara Indians. This phase was defined by excavations at the Lower Saratown site located along the Dan River. The site marks the arrival of European trade goods in the North-Central Piedmont, but little else seems to change.

Prior to 1670 the Sara were well-insulated from the Europeans. It is doubtful that many of the Sara during the Middle Saratown phase ever laid eyes on the English or felt the deadly sting of their diseases. The beads and trinkets that found their way to the Sara villages were passed along from Indian to Indian through traditional trade networks.

Settlement patterns during the Middle Saratown changed little from the preceding Early Saratown phase. The Sara continued to occupy large stockaded villages and populations were stable. No European influences are seen in settlement, subsistence, and technology. All this changed in the subsequent Late Saratown phase.

Late Saratown Phase (A.D. 1670 – 1710)

The Upper Saratown village, located along Dan River near its confluence with Town Fork Creek is the most extensively excavated Late Saratown village.

At the end of the Middle Saratown phase, about A.D. 1670, the flow of English-made goods reaching the Sara increased dramatically. Sometime after this European diseases struck with devastating force, making many of the excavated villages look more like cemeteries than habitation sites.

Community patterns changed drastically during the Late Saratown phase. The Upper Saratown site, occupied during the first half of the phase, consisted of a stockaded village occupied by between 200 and 250 persons living in circular houses. A very different pattern is seen by the close of the 17th-century, when the Sara communities are made up of widely dispersed households. Ceramic evidence suggests that fragments of ethnically diverse tribes may have merged with the Sara in these late sites to form a dispersed refugee community.

Pottery from the Late Saratown sites is called the Oldtown series. Smoothed and burnished surfaces are most common, followed by net-impressing. Most of the pots are large cooking or storage jars. Hemispherical and cazuela bowls were also found, often decorated with incised lines and punctations.

The basic subsistence pattern of the previous two centuries continued in the Late Saratown phase, with a balance between wild and native domestic food sources. Like other Piedmont Siouan phases, there is no evidence that European animals played a role in the subsistence cycle.

Mortuary patterns reflect dramatic changes during the Late Saratown phase. Large amounts of European-made ornaments, particularly glass beads and copper trinkets, accompanied burials, which were placed in the village within and near houses. At first, burials matched earlier forms, but toward the end of the phase a drastic change took place. Cemeteries with numerous shallow burial pits and very few associated artifacts were created away from villages, perhaps indicating awareness of the contagiousness of European diseases. The fact that most of the dead were subadults may indicate their deaths resulted from a single epidemic.

Close Contact in the North-Central Piedmont

Both the Appalachian foothills (the upper Catwaba valley) and the Appalachian Summit in western North Carolina were visited early on by the de Soto and Pardo expeditions in the middle 1500s. The Berry site, which was occupied during this time, appears to have been the town the Spanish described as Joara, when it was visited by the de Soto expedition in 1540 and by the Juan Pardo expedition from 1567-68.

After the Spanish expeditions, the Cherokee in and near the Appalachian Summit were insulated from European contact for a century. Some degree of trading and raiding were carried on with the Spanish settlements to the southeast. Then, in the 1670s, trade relations were set up with Virginia traders. In the early 18th-century English traders began to push west through the Blue Ridge mountains and along the upper Piedmont of South Carolina and Georgia. Here they found the Cherokee, a populous people in a widely scattered collection of towns. The Late Qualla phase represents Cherokee culture during this time period.

The Late Qualla phase (A.D. 1700 – 1838)

The Cherokee remain somewhat isolated until the close of the Tuscarora War in 1713. By the 1730s European diseases had spread to the Cherokee country. A smallpox epidemic in 1738-39 destroyed half of the tribe. During the mid-century the Cherokee were increasingly drawn into European rivalries and English, and later American, expeditions into the heart of Cherokee territory destroyed towns and killed many Cherokees. In these wars the Cherokee lost much of the political and military power they had previously possessed. Beginning with the Treaty of Hopewell in 1785 and culminating with the Removal of 1838 each treaty cost them more and more of their mountain homeland.

The pottery of the Late Qualla phase reflects the stability and conservatism that mark the beginning of this phase. No drastic changes demarcate the Late Qualla ceramics from pottery of the Middle Qualla phase.

Pottery from the Townson site, which dates to the second half of the Late Qualla phase, is similar to earlier Qualla pottery, but decorations are bolder in form and more crudely executed.

The Cherokee probably built both circular and rectangular houses. Throughout the Southeast, circular houses were used mainly as winter dwellings and rectangular houses were summer dwellings. After about 1776 rectangular houses became the dominant form.

House form at Townson also differed greatly from earlier rectangular Qualla houses. Instead of individual posts set in the ground, the walls of the house at Townson were formed by split rails laid one atop another and anchored to four corner posts. Cracks were chinked with clay. The house probably looked much like a contemporary Euro-American log cabin. However, inside the house was the traditional central puddled-clay hearth found in earlier Cherokee houses. A very similar Cherokee house was described in a letter relating the experiences of a soldier who participated in the 1776 attacks on Cherokee towns.

As house types changed during the Late Qualla phase, so did village configurations. Townson site consists of houses scattered along a terrace, whereas Middle Qualla villages were compact and usually stockaded. This process of population dispersion intensified as acculturation and pressures to change increased . By the time the Cherokee were forcefully removed in 1838 most families lived in isolated farmsteads and small hamlets.

Some Cherokee habitations had large numbers of artifacts, including non-native commercially manufactured items, while others contained mostly native-made items. These differences probably reflect varying degrees of acculturation and participation in the colonial market economy. Subsistence practices also changed. The Cherokees readily adopted Old World animals, and most families kept horses, cows, pigs, and chickens.

Although the population became more dispersed, town houses continued to be used and rebuilt at the same locations long after the main villages had been abandoned. The religious and ceremonial realms of Cherokee culture retained their traditional form and practice.

Close Contact in the Appalachian Summit

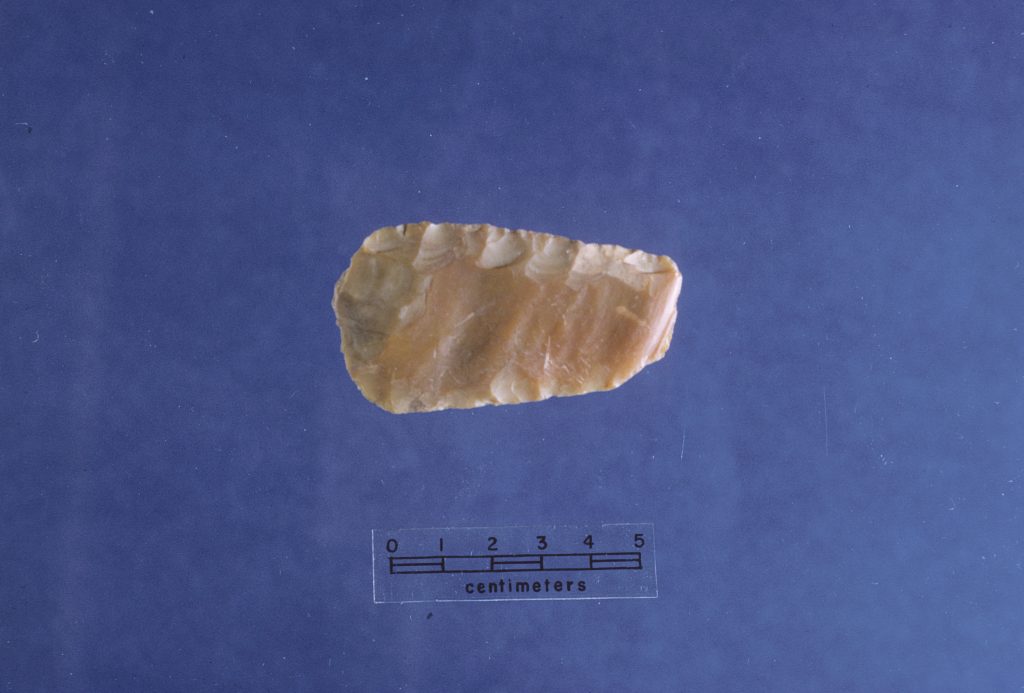

- Chipped-stone scraper from the Townson site in Cherokee Co., NC

- Clay pipe bowl from the Townson site in Cherokee Co., NC

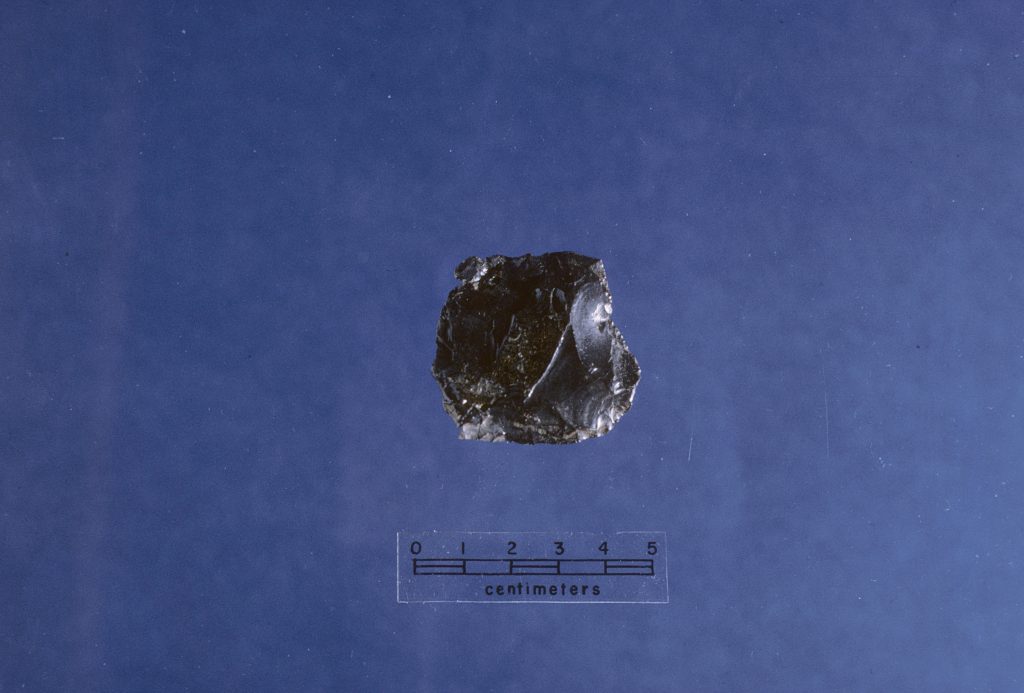

- Glass scraper from the Townson site in Cherokee Co., NC

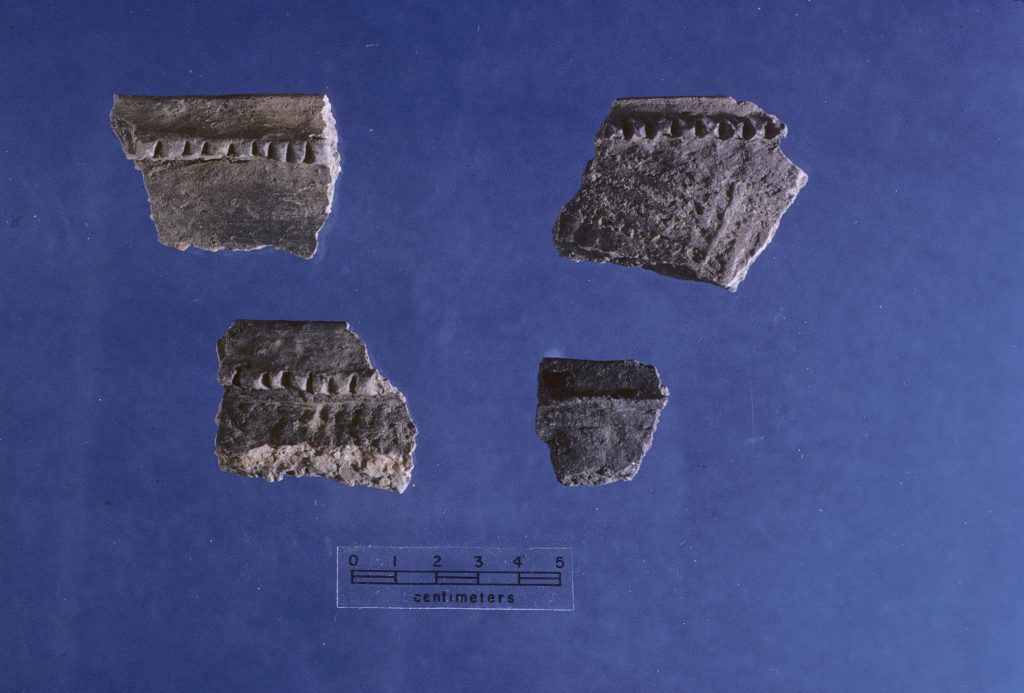

- Clay pipe fragments from the Townson site in Cherokee Co., NC

- Pottery fragments from the Townson site in Cherokee Co., NC

- Pottery fragments from the Townson site in Cherokee Co., NC

- Pottery fragments from the Townson site in Cherokee Co., NC

- Pottery fragments from the Townson site in Cherokee Co., NC

- Daub fragment from the Townson site in Cherokee Co., NC

- Daub fragment from the Townson site in Cherokee Co., NC

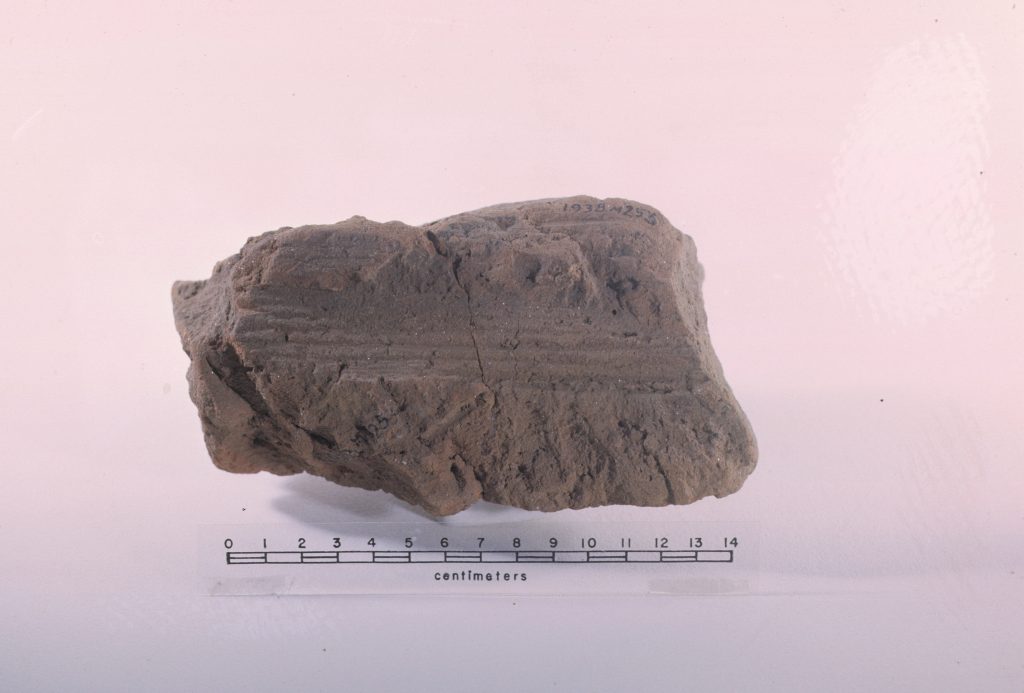

- Qualla jar fragment from the Tuckasegee site in Jackson Co., NC

- Qualla jar fragment from the Tuckasegee site in Jackson Co., NC