Archaic (8000–1000 B.C.)

The Archaic (8000 – 1000 B.C.) is an overarching time period covering over half of the timespan people have lived in North Carolina. This vast time has been explored by finding well-preserved deposits in rock-shelters and stratified, deeply-buried open sites in alluvial floodplains. The Archaic is generally thought of as a period dominated by nomadic, relatively small bands pursuing a hunting and gathering way of life, but there is evidence that some Archaic people settled into larger and more permanent sites relatively early.

Early Archaic

Hardaway (Stanly County)

Middle Archaic

Doerschuk (Montgomery County)

Gaston (Halifax County)

Late Archaic

Gaston (Halifax County)

General

Barber Creek (Pitt County)

Lowder’s Ferry (Stanly County)

Squires Ridge (Edgecombe County)

From the coast to the mountains, the Archaic began with wandering bands of hunters and gatherers who faced a wide variety of changing environmental conditions. These bands occasionally came together at favored locations along major river valleys, but most of their time was spent in small groups scattered across the landscape foraging for food and raw materials.

Toward the end of the Archaic, large groups began to settle down and live most, if not all year in areas rich in raw material and food resources. This settled life spawned the beginnings of plant domestication and use of pottery, hallmarks of the succeeding Woodland.

Close Regional

Numerous Archaic sites have been discovered on the North Carolina Coastal Plain and Coast. Unlike the Piedmont, where Archaic sites with stratified contexts have been excavated, the Coastal Archaic is known primarily from surface collections.

Archaic sites (base camps and small temporary sites) are widely scattered and can be found nearly anywhere near water. The number of sites generally increased through time. During the Late Archaic period, settlement shifted away from upland tributary streams toward the mouths of major rivers. Here hunting and fishing led to larger and more sedentary camps where pottery making and horticulture began. Diagnostic spear point styles recognized in the Piedmont are duplicated in the artifact collections from the coast.

Close Coastal Plain and Coast

As in the preceding Paleoindian span, much more is known about the Archaic in the Piedmont than either the mountains or the coastal areas. From the 1930s through the 1960s North Carolina sites in the Piedmont were especially important in Archaic research of the eastern United States.

In many parts of the country Archaic research focused on rock shelters, where dry alkaline conditions helped preserve organic remains. But in North Carolina, archaeologists were able to define long chronological sequences by excavating deeply buried, stratified sites in the alluvial floodplains of the Piedmont. In early excavations at buried floodplain sites such as Doerschuk and Lowder’s Ferry along the Yadin-Pee Dee River, and at the nearby Hardaway site, the cultural sequence was established that still defines the Archaic in North Carolina and throughout much of the eastern United States.

Early Archaic (8000 – 6000 B.C.)

The Early Archaic is generally viewed as the period when native populations began to adapt to an environment created by Holocene climatic conditions – conditions very similar to those of today. The Early Archaic in the Piedmont has been divided into two parts, the Palmer phase (8000 – 7000 B.C.) and the Kirk phase (7000 – 6000 B.C.).

Available subsistence information suggests that Early Archaic plant food collection focused on hickory nuts and acorns. Archaeologists presume that white-tailed deer provided the main source of meat. A dramatic increase in Early Archaic sites across the state suggests an increase in the overall population. Although subsistence strategies on the Piedmont changed little from those of the Late Paleoindian period, Early Archaic tool kits did change. New ways of attaching spears resulted in marked changes in the way points were made.

During the Palmer phase (8000 – 7000 B.C.) small, well-made end scrapers characteristic of the Late Paleoindian period continued to be made. During the Kirk phase (7000 – 6000 B.C.) scrapers were cruder and varied greatly in size and form. Adzes, gravers, drills, and perforators were made for working wood, hides, and animal bones into tools and ornaments. Cobbles were used as hammers and anvils to fashion other tools or crush and grind plant and animal resources. Groundstone tools are rare during the Early Archaic.

Early Archaic inhabitants were organized into small mobile bands (probably numbering 50 – 150 individuals). The North Carolina Piedmont offered a cornucopia of plant and animal foods, so the distribution of food resources may not have determined band territories. Some researchers believe Early Archaic bands ranged over entire drainage systems, while others believe that band territories were related to important stone resources and thus overlapped drainages.

Middle Archaic (6000 – 3000 B.C.)

During the Middle Archaic small kin-based groups moved from place to place pursuing a foraging subsistence strategy. The Middle Archaic in the Piedmont has been divided into three phases of about 1000 years each: Stanly, Morrow Mountain, and Guilford.

Simple but ubiquitous Middle Archaic tool assemblages suggest that new settlement and subsistence patterns (small, kin-related groups moving as units from place to place) formed as a response to climatic changes. This foraging pattern allowed groups to move more easily among the patchy, less predictable resources created under the warmer and drier conditions of the Middle Archaic.

Divisions of the Middle Archaic in the Piedmont are based on distinctive styles of spear points originally identified at Lowder’s Ferry and Doerschuk, sites in Stanly and Montgomery counties respectively. Deeply buried archaeological deposits at these sites, and at the Gaston site in Halifax County, show cultural continuities through the Middle Archaic.

Evidence for use of the atlatl, or spear-thrower, is first seen during the Stanly phase. Crude chipped-stone axes with lateral hafting notches have been recovered with Guilford points at the Gaston site. Other than these two innovations, there does not appear to be much that stands out about Middle Archaic tool assemblages.

Middle Archaic sites are numerous and appear to represent mostly temporary encampments. They occur across the Piedmont landscape without any obvious preference for particular environmental niches.

Late Archaic (3000 – 1000 B.C.)

In the Late Archaic, climatic conditions improved and there was a gradual trend towards more sedentary life. In the North Carolina Piedmont, it is difficult to walk over any plowed field with a nearby source of water and not find evidence of a Late Archaic campsite.

Although Late Archaic sites are numerous in the Piedmont, the full spectrum of Late Archaic culture is not found here. Large shell middens with cooking hearths, sand floors, and human and dog burials are found along the Atlantic coast. These vigorous, socially complex, semipermanent settlements are unlike any before. Similar sites are found along the broad shoals of the Savannah, Tennessee, and Green Rivers in Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, and Kentucky. It is at sites like these that pottery first appeared and native plants were gradually domesticated.

During the Late Archaic period, people living along the south Atlantic coast from Florida to North Carolina had begun to make fiber-tempered pottery. Stalling series pottery, made by molding lumps of clay and fibrous material into simple vessel forms, was made as early as 2500 B.C. By the beginning of the Woodland in North Carolina, several different ceramic traditions had been established across the state.

The most characteristic artifact of the Late Archaic period is a large, broad-bladed point with a square stem, called Savannah River Stemmed. Savannah River points indicate the Late Archaic period from New York to Florida. Late Archaic peoples also used hammerstones to peck and grind hard rocks into axes with grooves for hafting. They also made a variety of scrapers, drills, and other chipped-stone tools, as well as polished stone weights for atlatls.

During the latter half of the Late Archaic period, hemispherical bowls were pecked and carved from soapstone. Along the coasts of Florida and South Carolina, the first pottery vessels were invented at the end of the Late Archaic period.

Seeds and nuts were ground with stone mortars, and the use of fish nets is attested by notched stone pebbles that served as netsinkers. Squash and gourds were cultivated as early as the third millennium B.C. and, by the end of the Late Archaic period, sunflower, maygrass, and chenopodium were harvested as a precursor to active cultivation.

Close Piedmont

Very little Archaic period research has been conducted in the mountains of North Carolina. Some Late Archaic sites have been excavated (see below), but much of the reconstruction of Archaic chronology, settlement, and subsistence in the mountains leans heavily on research in neighboring southeastern Tennessee.

Early Archaic

No deeply buried, undisturbed Early Archaic components have been excavated in the North Carolina mountains. However, Early Archaic materials in southeastern Tennessee differ from those recovered at the Hardaway site in North Carolina. Other Early Archaic projectile point traditions, particularly side-notched and bifurcated base points, are present in the mountains. Most Early Archaic sites located in high, upland areas produce a wide range of tools reflecting hunting, butchering, hide working, and woodworking. Early Archaic groups established only temporary camps in the rugged Appalachian Summit region, while maintaining more permanent base camps in the Ridge and Valley province of east Tennessee. At these base camps in Tennessee, large quantities of charred acorns and hickory nuts were found, as well as prepared clay hearths. Impressions of basketry and textiles provide the earliest well-dated evidence of weaving in eastern North America.

Middle Archaic

The Middle Archaic period in the North Carolina mountains is indicated by the occurrence of Stanly Stemmed, Morrow Mountain Stemmed, and Guilford Lanceolate spear points (much the same as the Middle Archaic in the Piedmont). Most Middle Archaic settlements in the mountains consist of dispersed camps situated on a variety of valley and upland landforms. This dispersed settlement pattern may reflect the slightly warmer and drier conditions of the Altithermal climate. In contrast to Early Archaic tools, most Middle Archaic specimens were made from locally available rock. Stone atlatl weights provide the first concrete evidence for the use of the atlatl. Stone netsinkers suggest the increasing importance of fishing.

Late Archaic

The Warren Wilson site in Buncombe County and the Tuckasegee site in Jackson County contained Archaic strata and help archaeologists to understand regional practices during this period. Numerous rock hearths were present at Warren Wilson, as well as fragments of steatite bowls.

Riverine resources were no doubt important in the Late Archaic. Hunting and fishing were supplemented by harvesting large numbers of acorns and hickory nuts. Squash and gourds were cultivated as early as 3000 B.C. and towards the end of the Late Archaic period sunflower, maygrass, and chenopodium were well on the way to being domesticated.

Late Archaic Savannah River Stemmed and Otarre Stemmed spear points at the Warren Wilson site dated from about 3000 to 1500 B.C.

Close Mountains

- Soapstone vesel fragments from Transylvania Co., NC

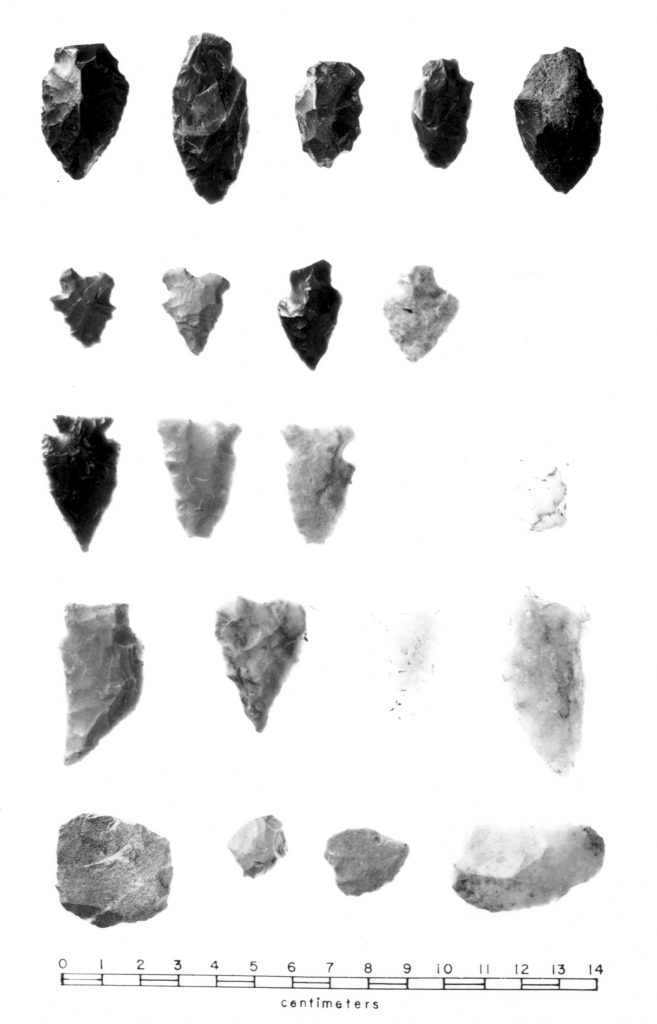

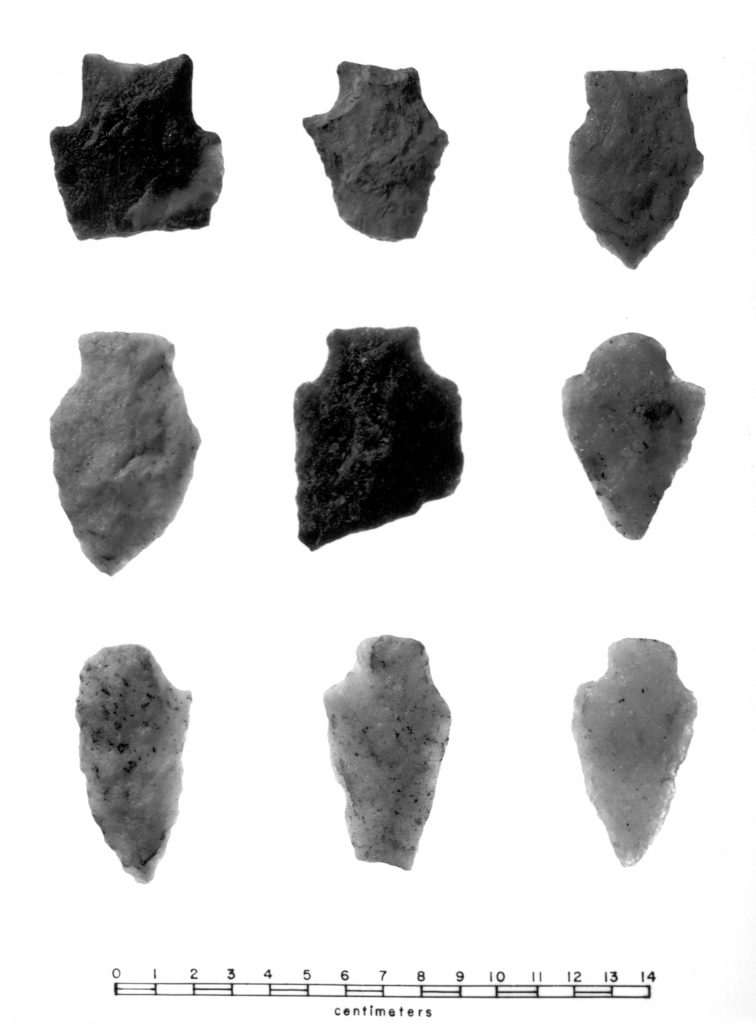

- Chipped-stone spear points and other tools from Transylvania Co., NC

- Morrow Mountain Stemmed spear points from Transylvania Co., NC

- Savannah River Stemmed spear points from Transylvania Co., NC

- Stone and ceramic artifacts in a private collection from Yancey Co., NC

- Grooved axe in a private collection from Yancey Co., NC

- Chipped-stone spear and arrow points in a private collection from Yancey Co., NC

- Grooved axes in a private collection from Yancey Co., NC

- Archaic spear points in a private collection from Yancey Co., NC

- Archaic spear points in a private collection from Yancey Co., NC

- Chipped-stone spear and arrow points in a private collection from Yancey Co., NC

- Archaic spear points in a private collection from Yancey Co., NC