Southern Piedmont

During the Paleoindian, Archaic, and Early and Middle Woodland, the archaeology of the Southern Piedmont is much like the rest of the Piedmont. However, the Southern Piedmont region is archaeologically unique within North Carolina during Late Woodland times. After A.D. 1000 the cultures located between the Uwharrie Mountains and the South Carolina border did not participate in the Piedmont Village Tradition. Instead they were influenced by the South Appalachian Mississippian Tradition.

During the Paleoindian, Archaic, and Early and Middle Woodland, the archaeology of the Southern Piedmont is much like the rest of the Piedmont. However, the Southern Piedmont region is archaeologically unique within North Carolina during Late Woodland times. After A.D. 1000 the cultures located between the Uwharrie Mountains and the South Carolina border did not participate in the Piedmont Village Tradition. Instead they were influenced by the South Appalachian Mississippian Tradition.

The Paleoindian is the time of the earliest generally accepted arrival of people in the southeastern United States – about 16000 years ago, or 14000 B.C. Although earlier migrations of people into the New World have been hypothesized, currently there is no firm evidence of people anywhere on the continental United States prior to 14000 B.C.

Our level of understanding of the Paleoindian period across the state is highly uneven, due to both the history of North Carolina archaeology and environmental and geological factors.

Paleoindian Chronology

Paleo-Indian in the Southeast is divided into the Early, Middle, and Late periods.

Spear points of the Early Paleoindian period (14000 – 9000 B.C.) are large, fluted lanceolates, very similar to the classic Clovis points of the West. What we know about the earliest inhabitants of North Carolina is based almost entirely on surface finds of these points. Concentrations of Early Paleoindian points have been noted in the Tennessee, Cumberland, and Ohio River valleys, as well as western South Carolina, southern Virginia, and the northern Piedmont of North Carolina.

In the Middle Paleoindian period (9000 – 8500 B.C.) the number of spear points increases considerably and regional variability in spear point forms emerge. The Cumberland, Suwanee, and Simpson point types are thought to be typical of this period. One thing all have in common is a narrowing or “waisting” at the base.

The Late Paleoindian period (8500 – 7900 B.C.) shows increased population growth. Dalton points are the diagnostic Late Paleoindian point type. By the end of the Paleoindian Holocene climatic conditions prevailed and the basic hunting and gathering lifeway that persisted for the next 5000 years was set.

Paleoindian Settlement and Subsistence

Paleoindian settlers in the Southeast found a rapidly changing landscape. Current evidence suggests that many of extinctions of Late Pleistocene megafauna – including the horse, mastodon, and mammoth – were complete by 8500 B.C.

East of the Mississippi River almost no Paleoindian tools have been found with these animals. Environmental differences between the Eastern and Western parts of the continent may have necessitated very different adaptations. By the middle Paleoindian period, if not earlier, the subsistence pattern was probably very similar to that of the Early Archaic period.

Most southeastern Paleoindian sites where more than a single point has been found are related to stone-quarrying activities. This pattern reflects a generalized foraging where groups rarely engaged in subsistence activities that produced recognizable traces in the archaeological record.

Paleoindian in the Piedmont

During the full glacial period (17000 – 14500 B.C.) before Paleoindians arrived, the Piedmont had been a boreal forest. As temperatures warmed conifers were replaced by deciduous forests (oak, hickory, walnut, elm, willow, and sugar maple) by 10,500 BC. Continued warming brought new forests of sweet gum, chestnut, red maple, and tupelo gum by 7000 B.C. When Paleoindians first came into the Piedmont winters were harsher and summers cooler than today. For about 1000 years, both people and now-extinct Pleistocene animals co-existed in North Carolina.

Hardaway is the most recognizable site name in North Carolina. Most stone tools found in the Piedmont are made from a fine-grained rhyolite that outcrops in the Uwharrie Mountains. Excavations at the Hardaway site in Stanly County have yielded tons of rhyolite tools and chipping debris dating to the Late Paleoindian and Early Archaic periods. The site was first recognized as important in the 1930s and excavations began after World War II.

The oldest component at Hardaway was represented by Hardaway-Dalton points, Hardaway Side Notched, and Hardaway Blades, which date from 8500 to 7900 B.C. Other stone tools associated with the Hardaway complex, such as unifacial end scrapers and side scrapers, are very similar to those used by Paleoindians. In the Piedmont, roaming bands of hunter-gatherer Paleoindians probably enjoyed a wealth of natural resources that were exploited seasonally.

Close Paleoindian

The Archaic (8000 – 1000 B.C.) is an overarching time period covering over half of the time-span people have lived in North Carolina. This vast time has been explored by finding well-preserved deposits in rock-shelters and stratified, deeply-buried open sites in alluvial floodplains. The Archaic is generally thought of as a period dominated by nomadic, relatively small bands pursuing a hunting and gathering way of life, but there is evidence that some Archaic people settled into larger and more permanent sites relatively early.

From the coast to the mountains, the Archaic began with wandering bands of hunters and gatherers who faced a wide variety of changing environmental conditions. These bands occasionally came together at favored locations along major river valleys, but most of their time was spent in small groups scattered across the landscape foraging for food and raw materials.

Toward the end of the Archaic, large groups began to settle down and live most, if not all year in areas rich in raw material and food resources. This settled life spawned the beginnings of plant domestication and use of pottery, hallmarks of the succeeding Woodland.

The Archaic in the Piedmont

As in the preceding Paleoindian span, much more is known about the Archaic in the Piedmont than either the mountains or the coastal areas. From the 1930s through the 1960s North Carolina sites in the Piedmont were especially important in Archaic research of the eastern United States.

In many parts of the country Archaic research focused on rock shelters, where dry alkaline conditions helped preserve organic remains. But in North Carolina, archaeologists were able to define long chronological sequences by excavating deeply buried, stratified sites in the alluvial floodplains of the Piedmont. In early excavations at buried floodplain sites such as Doerschuk and Lowder’s Ferry along the Yadin-Pee Dee River, and at the nearby Hardaway site, the cultural sequence was established that still defines the Archaic in North Carolina and throughout much of the eastern United States.

The Early Archaic (8000 – 6000 B.C.)

The Early Archaic is generally viewed as the period when native populations began to adapt to an environment created by Holocene climatic conditions – conditions very similar to those of today. The Early Archaic in the Piedmont has been divided into two parts, the Palmer phase (8000 – 7000 B.C.) and the Kirk phase (7000 – 6000 B.C.).

Available subsistence information suggests that Early Archaic plant food collection focused on hickory nuts and acorns. Archaeologists presume that white-tailed deer provided the main source of meat. A dramatic increase in Early Archaic sites across the state suggests an increase in the overall population. Although subsistence strategies on the Piedmont changed little from those of the Late Paleoindian period, Early Archaic tool kits did change. New ways of attaching spears resulted in marked changes in the way points were made.

During the Palmer phase (8000 – 7000 B.C.) small, well-made end scrapers characteristic of the Late Paleoindian period continued to be made. During the Kirk phase (7000 – 6000 B.C.) scrapers were cruder and varied greatly in size and form. Adzes, gravers, drills, and perforators were made for working wood, hides, and animal bones into tools and ornaments. Cobbles were used as hammers and anvils to fashion other tools or crush and grind plant and animal resources. Groundstone tools are rare during the Early Archaic.

Early Archaic inhabitants were organized into small mobile bands (probably numbering 50 – 150 individuals). The North Carolina Piedmont offered a cornucopia of plant and animal foods, so the distribution of food resources may not have determined band territories. Some researchers believe Early Archaic bands ranged over entire drainage systems, while others believe that band territories were related to important stone resources and thus overlapped drainages.

Middle Archaic (6000 – 3000 B.C.)

During the Middle Archaic small kin-based groups moved from place to place pursuing a foraging subsistence strategy. The Middle Archaic in the Piedmont has been divided into three phases of about 1000 years each: Stanly, Morrow Mountain, and Guilford.

Simple but ubiquitous Middle Archaic tool assemblages suggest that new settlement and subsistence patterns (small, kin-related groups moving as units from place to place) formed as a response to climatic changes. This foraging pattern allowed groups to move more easily among the patchy, less predictable resources created under the warmer and drier conditions of the Middle Archaic.

Divisions of the Middle Archaic in the Piedmont are based on distinctive styles of spear points originally identified at Lowder’s Ferry and Doerschuk sites in Stanly and Montgomery counties, respectively. Deeply buried archaeological deposits at these sites, and at the Gaston site in Halifax County, show cultural continuities through the Middle Archaic.

Evidence for use of the atlatl, or spear-thrower, is first seen during the Stanly phase. Crude chipped-stone axes with lateral hafting notches have been recovered with Guilford points at the Gaston site. Other than these two innovations, there does not appear to be much that stands out about Middle Archaic tool assemblages.

Middle Archaic sites are numerous and appear to represent mostly temporary encampments. They occur across the Piedmont landscape without any obvious preference for particular environmental niches.

Late Archaic (3000 – 1000 B.C.)

In the Late Archaic, climatic conditions improved and there was a gradual trend towards more sedentary life. In the North Carolina Piedmont, it is difficult to walk over any plowed field with a nearby source of water and not find evidence of a Late Archaic campsite.

Although Late Archaic sites are numerous in the Piedmont, the full spectrum of Late Archaic culture is not found here. Large shell middens with cooking hearths, sand floors, and human and dog burials are found along the Atlantic coast. These vigorous, socially complex, semipermanent settlements are unlike any before. Similar sites are found along the broad shoals of the Savannah, Tennessee, and Green Rivers in Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, and Kentucky. It is at sites like these that pottery first appeared and native plants were gradually domesticated.

During the Late Archaic period, people living along the south Atlantic coast from Florida to North Carolina had begun to make fiber-tempered pottery. Stalling series pottery, made by molding lumps of clay and fibrous material into simple vessel forms, was made as early as 2500 B.C. By the beginning of the Woodland in North Carolina, several different ceramic traditions had been established across the state.

The most characteristic artifact of the Late Archaic period is a large, broad-bladed point with a square stem, called Savannah River Stemmed. Savannah River points indicate the Late Archaic period from New York to Florida. Late Archaic peoples also used hammerstones to peck and grind hard rocks into axes with grooves for hafting. They also made a variety of scrapers, drills, and other chipped-stone tools, as well as polished stone weights for atlatls.

During the latter half of the Late Archaic period, hemispherical bowls were pecked and carved from soapstone. Along the coasts of Florida and South Carolina, the first pottery vessels were invented at the end of the Late Archaic period.

Seeds and nuts were ground with stone mortars, and the use of fish nets is attested by notched stone pebbles that served as netsinkers. Squash and gourds were cultivated as early as the third millennium B.C. and, by the end of the Late Archaic period, sunflower, maygrass, and chenopodium were harvested as a precursor to active cultivation.

Close Archaic

Three interrelated innovations marked the end of the Archaic and the beginning of the Woodland: pottery-making, semi-sedentary villages, and horticulture. All had their origins in the Archaic but became the norm during Woodland times.

The widespread appearance of pottery-making is viewed as going hand in hand with an increasing reliance on seed crops and more permanent settlement. Domestication of early cultigens laid the groundwork for later acceptance of tropical cultigens. Corn was not widely grown until after A.D. 700 and did not become an important food crop in many areas until after A.D. 1000. With the introduction of beans around A.D. 1200, the eastern agricultural triad of corn, beans, and squash was completed.

In North Carolina, the Woodland is divided into Early, Middle, and Late periods. Along the coast and through much of the Piedmont, the Late Woodland continues until Contact, while in the Appalachian Summit, Western Foothills, and the Southern Piedmont, Mississippian and Mississippian-influenced societies developed after A.D. 1000.

The Woodland cultures of the North Carolina Piedmont were only marginally influenced by cultural traditions elsewhere in the eastern United States. The rich and elaborate Hopewell and Swift Creek cultures that influenced wide areas of the Southeast had little impact on cultural developments in the Piedmont. And the powerful Mississippian chiefdoms that later dominate most of the Southeast were only able to penetrate the southern fringe of the Piedmont.

Piedmont Tradition Early and Middle Woodland Periods (1000 B.C. – A.D. 800)

Although we know relatively little about their origins during the Early Woodland period, cultures throughout most of the Piedmont steadily evolved along an unbroken continuum from about A.D. 1000 until the time of first contacts with Europeans. Subsistence seems to have remained evenly balanced between crop production and wild plant and animal resources. Social distinctions were based primarily on age and sex. Egalitarian Woodland societies were woven together by kinship and leadership roles were achieved rather than ascribed.

Only in the southern Piedmont is the Piedmont Village Tradition broken by the spread of the South Appalachian Mississippian tradition into the Yadkin-Pee Dee River Valley.

The stratigraphic and stylistic relationships among various ceramic types during the first half of the Woodland period are still unclear. Badin, Yadkin, Vincent, and Clements series ceramics are guides to occupations of the Piedmont during this time.

Aquatic resources are important during this time and a wide variety of mammals and birds were eaten. Several species of weedy plants, including maygrass, knotweed, goosefoot, and sunflower, although no direct evidence of these practices have yet been found in the Piedmont.

During this time the bow and arrow completely replaces the atlatl.

Badin Phase (ca. 500 B.C. ?)

The Badin phase is named for the small Stanly County town. Near Badin, at the Doerschuk site, the Badin ceramic series was found in a soil zone overlying the Late Archaic Savannah River level.

At the Doerschuk site in Stanly County, the Badin ceramic series was found in a soil zone overlying the Late Archaic Savannah River level. Badin vessels, well-made and tempered with sand, were simple in form, consisting of straight-sided jars with conical bottoms. Vessels were stamped with cord-wrapped and fabric-wrapped paddles. Badin ceramics appear to be related to the Early Woodland Deep Creek wares of North Carolina’s coastal region.

In addition to the abrupt introduction of ceramics, an entirely different form of projectile point was thought to be associated with the Badin Phase. Crudely flaked, triangular “Badin” points represent quite a departure from the large, stemmed spear points of the Savannah River phase.

Based primarily on radiocarbon dates for the succeeding Yadkin phase, archaeologists think that the Badin phase must date to around 500 B.C. One thing that is surprising in the North Carolina Piedmont is the small number of Badin and Yadkin phase sites compared to the relatively large number of Late Archaic Savannah River phase sites.

Otherwise, we know very little about aboriginal life styles during the Badin Phase. Probably very little changed from the Late Archaic period except for the gradual incorporation of the bow and arrow and ceramic containers. Technology was still primarily adapted to a hunting-and-gathering way of life.

Yadkin Phase (ca. 300 B.C. – ca. A.D. 800?)

The Yadkin ceramic series, which is thought to follow after Badin ceramics, was also defined at Doerschuk site. Yadkin is similar to Badin except for being tempered with crushed quartz. Cord-wrapped and fabric-wrapped surfaces persist, but new kinds of surface treatments – check stamping, linear check stamping, and simple stamping made with carved wooden paddles – are added. These treatments tie Yadkin phase pottery to the Early Woodland Deptford wares common in Georgia in South Carolina. Yadkin projectile points are typically large triangular forms that resemble Badin points but are more finely flaked.

Radiocarbon dates for Yadkin and Yadkin-like ceramics generally fall between 290 B.C. and A.D. 60, so it is unclear whether Badin ceramics predate Yakin in all areas of the Piedmont. Some Yadkin sites may have been occupied for relatively long periods of time and lasted until the latter part of the phase, around A.D. 500.

Yadkin phase sites occur more frequently than Badin phase sites, especially in the southern Piedmont and the South Carolina Coastal Plain. Still, evidence relating to the way Yadkin people lived are rare. As Early Woodland research continues across the Piedmont, we will probably see more and more variability in the early ceramic traditions and find that what holds true for one region may not hold true for another.

Southern Piedmont Late Woodland

The Southern Piedmont region is archaeologically unique within North Carolina. During most of Late Woodland times cultures here did not participate in the Piedmont Village Tradition. Instead they were influenced by South Appalachian Mississippian.

Between A.D. 1000 and 1400, Mississippian-influenced societies developed from the coast of Georgia to the mountains of North Carolina. Known archaeologically as Etowah, Wilbanks, Savannah, Pisgah, Irene, and Pee Dee, these politically complex cultures built mounds for the elite, participated in elaborate ceremonialism, and sometimes ruled over large territories.

Pee Dee Culture (A.D. 1000 – 1500)

In the Southern Piedmont, the expression of the South Appalachian Mississippian tradition is the Pee Dee culture. The Town Creek site, on the Little River in Montgomery County near its confluence with Town Fork Creek, is the most important Pee Dee site. Once thought to be a movement of people that arrived in the Piedmont with an entirely new way of life, Pee Dee is now viewed as a regional center of South Appalachian Mississippian that interacted and evolved with other regional centers scattered from the Coastal Plain of Georgia and South Carolina to the western North Carolina mountains.

Excavations at Town Creek began in 1937 and continued off and on for the next fifty years. Designated a state historic site in 1955, Town Creek remains North Carolina’s only state historic site dedicated to its native population.

The mound at Town Creek faced a large plaza where public and ceremonial activities took place. Several structures, including some that may have served as burial or mortuary houses, were constructed around the edge of the plaza. The mound was constructed over an early rectangular structure described as an earth lodge. After this structure collapsed it was covered with a low earthen mound that served as a platform upon which a temple was erected. After this structure burned a thick layer of soil was added to enlarge and heighten the mound and another temple was built. The mound, plaza, and habitation zone were enclosed by a stockade made of closely set posts. There were five episodes of stockade building.

Although not visible like the mound, a large number of burials were present at Town Creek. Several were clustered in mortuary areas. Most were loosely flexed and placed in simple pits. A few were fully extended or reburied as bone bundles. Several infants and small children were tightly wrapped and buried in large pottery vessels called burial urns. A few of the Pee Dee burials were richly adorned with a variety of exotic artifacts made from copper and shell. Copper artifacts include copper-covered wooden ear spools and rattles, pendants, sheets of copper, and a copper axe. Beads, gorgets and pins were fashioned from conch shell.

There are strong similarities between Pee Dee pottery and pottery from other South Appalachian Mississippian sites in South Carolina and Georgia. The ceramics most similar to Town Creek pottery came from the Irene site near Savannah, Georgia.

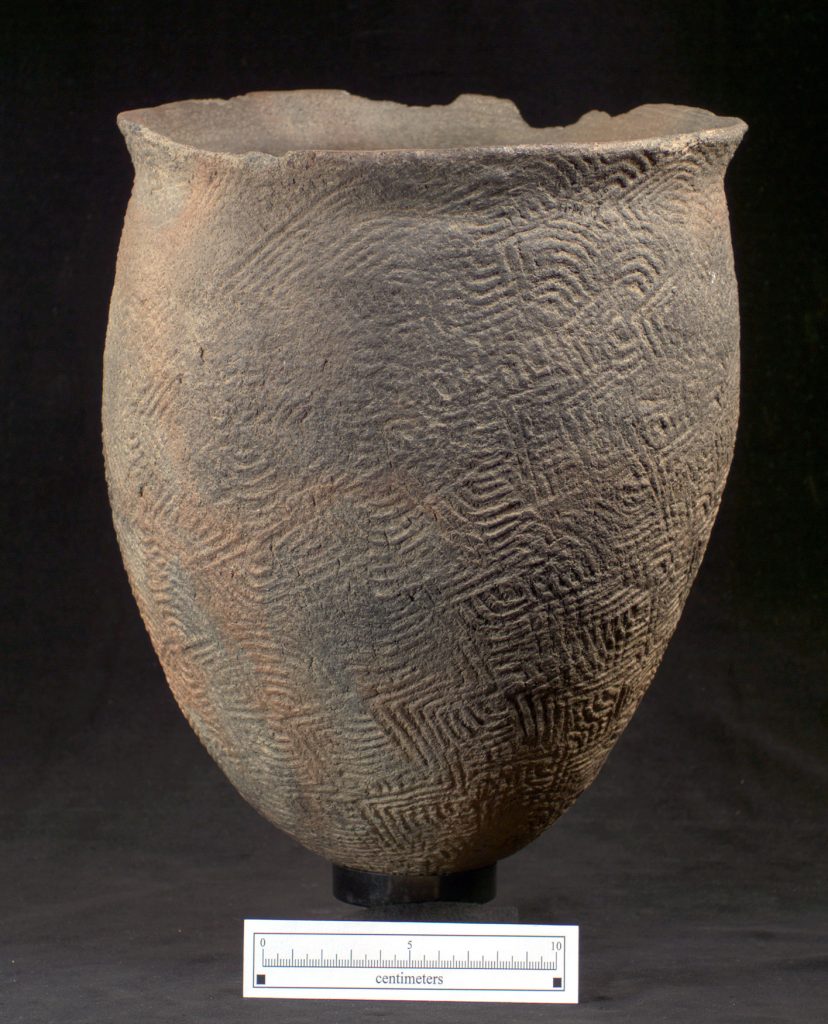

Earlier pottery at Town Creek is more often hemispherical bowls and jars with complicated stamped surfaces. The most popular early designs are a series of concentric circles, followed by filfot cross designs. The filot cross later replaced concentric circles as the more popular surface finish. Plain and burnished surface treatments increased and cazuela bowls became more popular. Another treatment, textile wrapping, appears late and is unique to Pee Dee pottery.

Pee Dee Culture at Town Creek did not suddenly appear but evolved over a period at least 200 years. The fourteenth century saw the decline of many South Appalachian centers like Irene and Town Creek. As temple mounds were abandoned, burial practices changed to reflect a more egalitarian society. Focusing on outlying villages without mounds clarifies Pee Dee Culture before and after Town Creek.

Teal Phase (ca. A.D. 1000 – 1200)

Early Pee Dee culture began between A.D. 980 and 1160. Pee Dee complicated stamped pottery was accompanied by fine-cordmarked and simple stamped types called Savannah Creek. Subsistence was based on hunting, fishing, and farming. Little is known of domestic architecture, although some ceremonial structures and burials have been found.

Town Creek Phase (A.D. 1200 – 1400)

This is the time when the mound was constructed at Town Creek and the site became the ritual and ceremonial center of the Pee Dee drainage. A substantial residential population was present at the site. Although maize agriculture was a mainstay, hunting, fishing, and gathering remained important. Except for the elaboration of ritual activities, Pee Dee culture continued much as before.

Leak Phase (ca. A.D. 1400 – 1500)

As Town Creek’s importance began to wane around A.D. 1400, the Leak site grew in size and importance. The popularity of complicated stamped, plain, and textile wrapped surfaces and cazuela forms increased. Oval houses were constructed and subsistence practices changed little.

Caraway Phase (A.D. 1500 – 1700)

Following the end of Pee Dee Culture in the southern Piedmont, the Caraway phase represents a return to the mainstream of the Piedmont Village Tradition. Only a few vestigial ceramic traits and abandoned villages remained to hearken the accomplishments of the Pee Dee Culture.

The Caraway phase was first recognized at the Poole, or Keyauwee site, on Caraway Creek in Randolph County. Although a few European trade artifacts are found at Keyauwee, most of the materials date to late in the Late Woodland period – around the beginning of the sixteenth century. The shell and bone artifacts are very similar to the grave goods found at sites dating to the Hillsboro, late Dan River, and Early Saratown phases.

The Caraway phase is the Southern Piedmont’s version of the widespread Lamar style. Caraway ceramics represent the culmination of the Badin, Yadkin, Uwharrie, and Dan River ceramic traditions with an overlay of some Pee Dee influence. Smooth or burnished surfaces predominate, followed in popularity by complicated stamped and simple stamped surface treatments. The smooth and burnished types probably date later than the stamped treatments.

Excavations at Keyauwee site in the 1930s found pits with village refuse in the western portion of the site and burials in the eastern portion. Individual burials were placed in flexed position and accompanied with a variety of artifacts, including bone and shell beads, shell gorgets, stone discoidals, and a stone pipe. The stone pipe is very similar to one found at the Gaston site.

Close Woodland

The time of contact between Indians living in North Carolina and Europeans arriving from Spain and England varied considerably across the state. The expedition of Hernando de Soto passed through western North Carolina in the spring of 1540. Pardo’s expeditions into the same areas came less than 30 years later. The first English attempts at settlement in northeastern North Carolina came about 20 years after that, starting in 1584. But it was not until after about 1650, when English explorers, traders, and settlers came from Tidewater Virginia, that North Carolina’s Indians felt the brunt of the European presence on their land.

Accordingly, the beginnings of these arrivals do not necessarily herald the beginnings of significant changes in the histories of North Carolina’s tribes. Overall, however, this was a time of sweeping and often devastating change.

Contact, Interaction, and Cultural Change in the Piedmont

Between 1936 and 1941 the University of North Carolina’s first Siouan Project searched the Piedmont hoping to locate and identify historic Siouan villages described in the 17th and 18th century. Results were inconclusive. A return to this research four decades later, under UNC’s second Siouan Project, had much better success in exploring the question of what happened to the state’s native inhabitants as European explorers, traders, and settlers moved into the North Carolina backcountry during the last half of the seventeenth century and early eighteenth century.

Trade

In the timespan from A.D. 1600 to 1670, only a few glass and brass/copper beads found their way into the Piedmont villages. These items were exchanged through native intermediaries operating their traditional trade networks. During the 1670s, however, trade changed dramatically as Virginia traders began making regular trips into the backcountry searching for new markets.

The intensification and spread of the peltry trade is directly reflected in sites of the 1670 to 1710 period (the Late Saratown and Fredricks phases). Literally thousands of beads and other ornaments, but few tools and weapons, moved into the Sara sites on the upper Dan River, while guns, knives, hatchets, beads, and trinkets were obtained in quantity by the central Piedmont Occaneechi, who controlled the flow of goods to the more remote Sara. After 1680, with the Occaneechi stranglehold broken, the Sara gained access to weapons and other tools.

European tools and ornaments were used alongside their counterparts made with traditional technologies, rather than replacing them. This flow of goods had a greater impact on social structure, however. Whereas authority and prestige had been accorded primarily to women in the earlier seventeenth century, men’s routes to status were enhanced when trade in European goods greatly increased.

Intertribal Relations

Intertribal conflict and warfare certainly preceded the arrival of Europeans. However, hostilities increased dramatically when Indian slaves and deerskins could be traded for the kettles and guns of the Europeans. Human skeletons scarred by scalping and bullets are clear evidence of hostilities. Conflicts often took the form of raids from as far away as New York and Pennsylvania.

Whereas in the past blood feuds and revenge fueled the fires of conflict, new motives and new ways of conducting warfare were introduced along with European weapons. Unprecedented opportunities to exert economic and political power were available by controlling the flow of trade and acquiring weapons.

Subsistence

Archaeological evidence has shown that the new plants and animals brought by Europeans were virtually ignored by most Piedmont Indians during Contact. The exceptions to this were peaches and watermelons, which were widely planted and often reached native communities well in advance of the Europeans themselves. Outside of these two fruits, the traditional trinity of native crops (corn, beans, and squash) remained the mainstay. Likewise Old World animals were seldom raised, probably due to the significant changes in habitation that their care required.

As was the case with tools and trinkets, only those items that did not require a re-organization of the traditional ways of doing things were incorporated, and these were used alongside of, not in place of, familiar resources.

Disease

Without a doubt, the most devastating result of the European arrival on groups living in the North Carolina Piedmont was the introduction of new diseases for which the native populations had little or no resistance. Smallpox, measles, and other viral diseases swept the region, killing and disabling thousands. This devastation was accelerated during the late 1600s by increased population movements and expanded intertribal contact as native people adapted to the economic and political changes brought about by the trade.

Spread of Old World diseases depended on a number of local and regional factors. Population density, community size, and degree of contacts all affected the timing, speed, and scope of disease events.

Despite this devastation, North Carolina today is the home of the largest Native American population east of the Mississippi River. The robust cultural diversity seen in the archaeological record of the last 12,000 years survives today in the tribal traditions of North Carolina’s native peoples.

Close Historic

- Stone gorget fragments from the Leak site in Richmond Co., NC

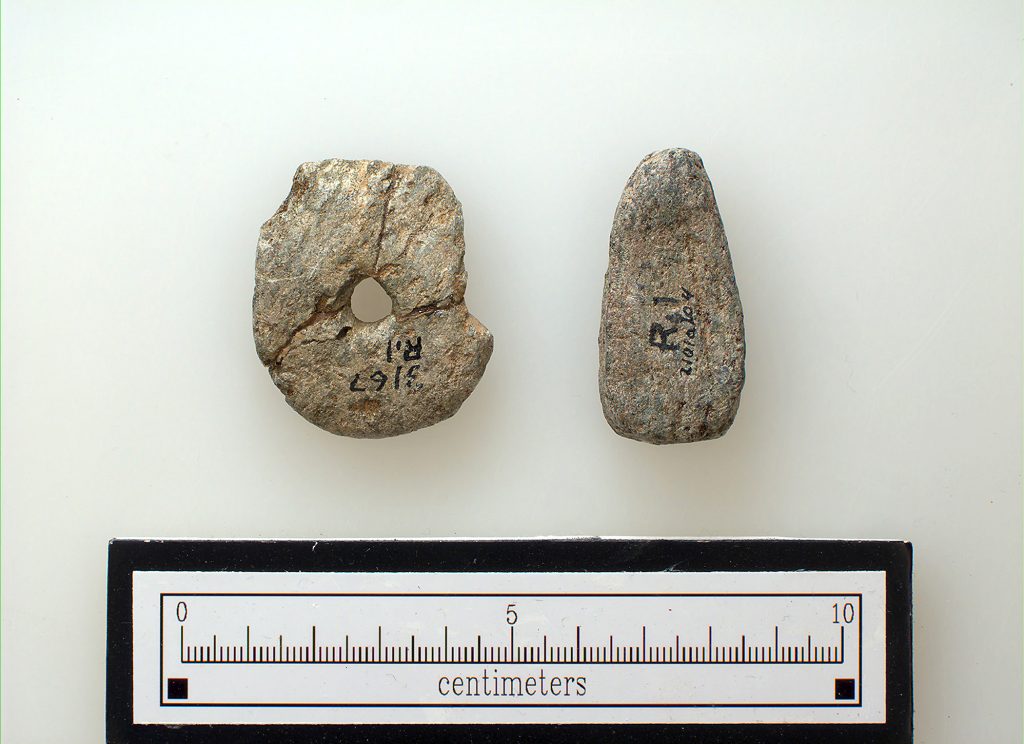

- Soapstone objects from the Leak site in Richmond Co., NC

- Pottery disks from the Leak site in Richmond Co., NC

- Spatulate axe or spud fragment from the Leak site in Richmond Co., NC

- Chipped-stone bifaces from the Tucker’s Store site in Richmond Co., NC

- Chunkey stone fragment from the Stanback Ferry site in Richmond Co., NC

- Chipped-stone biface from the Stanback Ferry site in Richmond Co., NC

- Pee Dee Plain bowl from the Leak site in Richmond Co., NC

- Pee Dee Complicated Stamped jar from the Leak site in Richmond Co., NC

- Pee Dee Plain pot from the Leak site in Richmond Co., NC

- Chipped-stone Dalton adzes from the Hardaway site in Stanly Co., NC

- Atlatl weight fragments from the Hardaway site in Stanly Co., NC