Fredricks (Orange County)

The Fredricks site (31OR231) is a historic Occaneechi village that was visited in 1701 by the traveler John Lawson. The fact that Lawson was able to see the village when he was traveling along the Great Trading Path is something of a stroke of luck, as Fredricks was only occupied for about a decade, roughly between A.D. 1690-1710. The site was excavated as part of the Siouan Project, which was restarted in 1983. The goals of the Siouan project were to study culture change in the Piedmont during the Contact period and to understand the effects of European explorers, traders, and settlers who came into the North Carolina back-country during the last half of the 17th century and the early 18th century.

History of Excavations

The first excavations actually took place at what is now the Wall site, in order to determine if it was the historic Occaneechi town. Although excavations in the vicinity of the Wall site did not turn up historic artifacts, testing other areas of the large field revealed some English kaolin pipe stems and aboriginal pot sherds in a small garden plot about 100 yards west of the Wall site. Further subsurface testing in a grassy area next to the garden showed that there were intact cultural features in the soil. Excavation showed that these were graves that were part of a cemetery associated with a Contact-period Indian village. The site was named Fredricks and was completely excavated between 1983 and 1986 in anticipation of construction at the site. The location of the site, along with the associated trade artifacts, ultimately indicated that this was, indeed, the site of the Occaneechi village visited by John Lawson in 1701.

Who Were the Occaneechis?

Before 1676, the Occaneechis were a powerful tribe living in Virginia. They were able to become middlemen in the Virginia trade, and by using firearms and intimidation were able to control the flow of European trade goods to more remote groups like the Sara. Initially, they lived along the principal trading path out of Fort Henry. More specifically, the Occaneechis lived on Occaneechi Island, on the Roanoke River, just below the confluence of the Staunton and Dan Rivers. The Occaneechi were so successful in their role as middlemen that prominent Virginia trader Abraham Wood noted that they were “the Mart for all the Indians for at least 500 miles” (Anonymous 1871:167). This stranglehold was broken by Bacon’s Rebellion, at which point other groups finally had the opportunity to receive the full range of English trade goods.

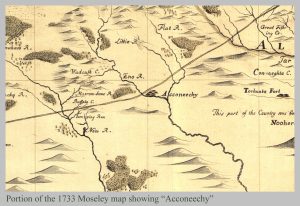

Sometime before 1700, the Occaneechi migrated south and established a village along the Eno River. By the early 1710s, however, they had moved back to Virginia at Fort Cristanna and were under the protection of the Virginia colonial government. In 1701, John Lawson visited the Eno River village while on his travels, and wrote down a brief description of it, calling it “Aconechy Town.” He encountered the village on the north side of the Eno River near the Great Trading Path’s crossing point. The crossing, as well as the village, were depicted on a 1733 map of North Carolina made by Edward Moseley.

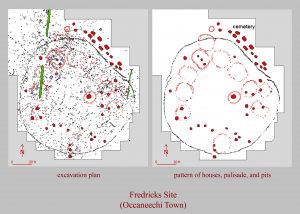

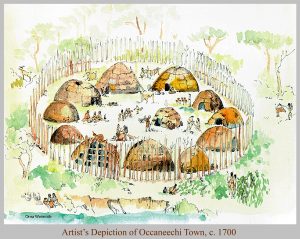

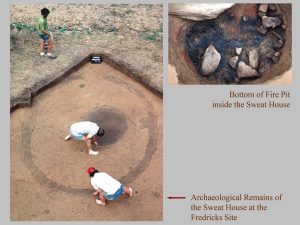

The town itself was a small, stockaded village, meaning that the houses were surrounded by a wall made of logs placed side by side vertically, with the tops sharpened. The entire village was only about a quarter of an acre in size. By this time, European diseases and warfare had truly decimated Piedmont groups, including the Occaneechi. Archaeologically, we can see that the stockade itself was a single line of small posts, surrounding no more than 10-12 houses. Some houses were oval and made up of individual wall posts, while others had trenches in order to set the wall posts; these were all arranged around an open plaza. At the edge of the plaza was a communal sweat lodge, about 10 ft in diameter with a large, central fire pit. Overall, there were probably fewer than 75 individuals living in this village, while the lack of rebuilding or extensive repairs indicates that the Occaneechi probably lived there for less than a decade.

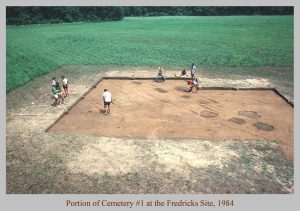

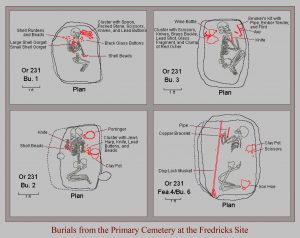

Stockaded villages, which are an indication of inter-tribal conflict and warfare, preceded European arrival in the Piedmont. Violence increased during the Contact period, however, as a result of the trade in deerskins and Indian slaves. This violence is attested to by some of the burials that were recovered from the village. One grave contained the scarred skull of a scalp victim, while another grave held the remains of a young woman with a lead ball flattened against her shin. In total, 25 graves were excavated from three different cemeteries located outside the stockade wall. These people would have represented at least a third of the already small Occaneechi group, which is a very high mortality rate. The graves themselves changed from the earlier shaft-and-chamber burial pits to rectangular straight-sided pits dug with metal tools. The bodies were still placed in their graves flexed, but the burials were no long placed in and around dwellings. Instead, the three cemeteries consisted of multiple grave clusters that were carefully aligned in rows.

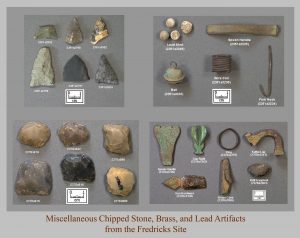

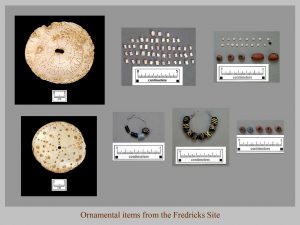

Each cluster contained an adult female and one or more juveniles, leading archaeologists to interpret the clusters as family units. Grave goods recovered during the excavations show the intensified trade between the English and Piedmont groups; knives, tobacco pipes, hoes, kettles, guns, beads, and ornaments were all recovered from the burials. Despite their easy access to European weapons and cutting tools, the Occaneechi still continued to make and use stone tools in the same types of styles that can be traced back several hundred years. Stone tools found at Fredricks include small triangular points, drills/perforators (for making holes), gravers (used for carving), scrapers (for working hides), many kinds of used and re-worked flake tools, and manos and milling stones (for grinding plants and seeds). Shell ornaments, including gorgets, columella beads, disk beads, wampum, and runtees (circular shells), were also found at Fredricks, but these were probably made by groups living along the Atlantic coast and traded to the Occaneechis.

Cemetery 1 contained thirteen individuals from three families and was located next to the Fredricks site stockade. Cemetery 2 contained four graves from one family, and was located between the Fredricks and nearby Jenrette stockades. And Cemetery 3 contained eight graves from two families, and was located just inside the stockade that surrounded the Jenrette village. While Jenrette was most likely abandoned by the time the Occaneechis settled in the area, the alignment of the graves suggests that the stockade wall may have still been standing. Archaeologists are not exactly sure why there are three separate cemeteries, but it is possible that they reflect the different ethnic groups that were forced to band together with the Occaneechis as a result of the depopulation occurring at the time.

Sources

Ward, Trawick H., and R.P. Stephen Davis, Jr.

1998 • Time Before History: The Archaeology of North Carolina. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.