Gaston (Archaic)

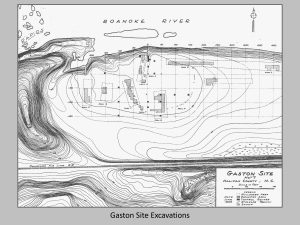

The Gaston site (31HX7) is located in Halifax County in an area of narrow floodplain on the Roanoke River. Gaston was a site that we call multi-component, meaning that many different people lived at it over many different time periods. It was excavated by Stanly South, who uncovered a Middle Archaic component underneath a Late Archaic zone.

History of Excavations

Archaeological research within the Roanoke Rapids Reservoir was part of a large program of salvage archaeology. The plans of the Virginia Electric and Power Company (VEPCO) were to build a hydroelectric dam that would create Roanoke Rapids Lake on the Roanoke River, thus flooding the entire area. During the initial archaeological survey phase, 73 sites were recorded and six were tested, including Gaston. Stanly South, Jewel South, and Lewis Binford worked from sunrise until sunset every day of June until the site was flooded on June 29, 1955.

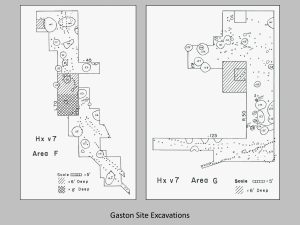

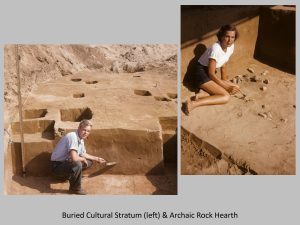

The archaeologists excavated 20 5ft-by-5ft squares by hand in order to determine site stratigraphy and provide control for the mechanized stripping that was to follow. The mechanical stripping exposed 200 features, most of which were interpreted as “garbage pits” or “fire pits”. In addition to these pits, the exposed features also included houses and both human and dog burials.

Research at Gaston

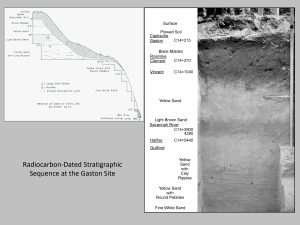

The Gaston site was particularly important due to its stratigraphic integrity, or the fact that the layers of soil built up over time and were not disturbed. This allowed archaeologists to use soil attributes to help isolate cultural components from different time periods. The two periods that Gaston provided the most information about were the Archaic and the Late Woodland.

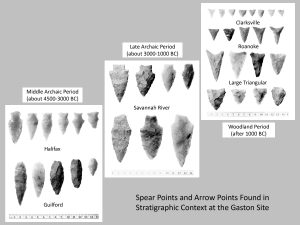

The excavations done by the Souths and Binford uncovered two Archaic components at Gaston – a Late Archaic component, and a Middle Archaic component underneath. Their investigations produced a new style of Middle Archaic point, called the Halifax Side-Notched. These points are similar to Guilford Lanceolate points, but are shorter than Guilfords and have very shallow side notches. The sequence of Stanly, Morrow Mountain, Guilford, and Halifax points represents an interesting debate within archaeology. Initially, it was believed that these points each represented a different group of people – as one group moved into the area, they brought their points and other cultural traditions with them. More recent research, with an eye towards how stone tools are made, used, and reused, indicate that there are more similarities than differences between the different points. Rather than multiple sequential groups, this suggests that the same people were using and creating all of these points. This latter explanation is supported by more recent excavations, where the various Middle Archaic point types are found mixed together throughout most of the deposits, suggesting that they were used at roughly the same time.

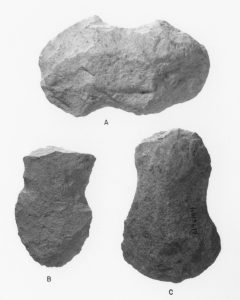

Outside of the point debate, another innovation during the Middle Archaic was chipped-stone axes. Axes with hafting notches on the sides have been recovered along with Guilford points at Gaston. While atlatls also would have been in use during the Middle Archaic, no atlatl weights were recovered during the Gaston excavations. Besides spear points, atlatl weights, and axes, Middle Archaic people appear to have had few formal tools. Rather than shaping tools specific to various tasks, people knocked off expedient flakes with sharp edges that were then used for scraping and cutting tasks.

Based on what we know from Middle Archaic excavations in North Carolina and elsewhere, it appears that most sites are temporary encampments, based on the numerous discarded tools. These camps show up across the landscape, indicating that Middle Archaic peoples did not have a preference for any particular environmental niche. That being said, there do appear to be some differences in occupations. Areas between rivers seem to have a higher number of Middle Archaic sites, while floodplain settings have larger and more extensive sites. Blanton and Sassaman (1989) suggest that these differences are probably related to the differences in these landforms and the ways in which people could reoccupy them. The flat topography of floodplains offers more space to spread out (larger sites) and allowed people to easily reoccupy the same space multiple times (more extensive). Alternately, the ridge tops between river areas are more restricted, so reoccupation would have meant finding a different area to encamp (more sites, smaller in area).

The tools found at Middle Archaic sites tell us that people subsisted through foraging. The distribution of sites also suggests that people lived primarily as small, probably kin-related group, moving from place to place as a unit while they obtained food and other materials. This shift in settlement pattern that occurred at the end of the Early Archaic may be a result of changing climate. Between 6,000 B.C. and around 2,000 B.C. the weather became warmer and drier, a period referred to as the Altithermal or Climatic Optimum. The result of this climate change was a patchy, less predictable environment, requiring people to be flexible and inventive – a lifestyle that foraging is well suited to. As climatic conditions improved, we see an increase in population and the beginnings of a trend towards more sedentary life beginning in the Late Archaic.

Late Archaic camp sites in North Carolina are somewhat different than what can be seen elsewhere. Along the south Atlantic coast, Late Archaic sites include large shell middens with cooking hearths, sand floors, and human and dog burials. Along the shoals of the Savannah, Tennessee, and Green Rivers, archaeologists find large middens made of the shells of freshwater mollusk remains. While we don’t get large shell middens in the North Carolina Piedmont, at sites like Doerschuk, Lowder’s Ferry, and Gaston, thick deposits of organic soil associated with the Late Archaic indicate an intensity of occupation that is a clear departure from the preceding Early and Middle Archaic periods. Small, circular pit-hearths lined with stones are another piece of evidence that indicate people were settling down with an increased degree of permanence.

One of the typical horizon markers for the Late Archaic, from New York to Florida, are Savannah River Stemmed spear points, named after the location where they were first recognized in a Late Archaic context (Stalling’s Island, on the Georgia side of the Savannah River). Although referred to as spear points, they were probably used for many cutting tasks, along with serving as spear tips. Other innovations during the Late Archaic include the use of hammerstones to peck and grind axes with hafting grooves, and the use of steatite to make bowls that could be used to cook foods directly over a fire.

While no food remains have been analyzed from a Late Archaic context in the North Carolina Piedmont, the geographic location of sites like Gaston help archaeologists to understand the kinds of foods people may have been eating. Gaston, along with Doerschuk and Lowder’s Ferry, is located along a major stream, suggesting that fish, turtles, and migratory water fowl were important seasonal foods. Freshwater mussels may have been important as well. Small temporary camps are found in the uplands between rivers and indicate that Late Archaic peoples relied on hunting animals like white-tailed deer, bear, and other small mammals, as well as gathering foods like acorns, hickory nuts, and a variety of wild fruits and berries.

Close Archaic

As a result of time constraints at Gaston, South made the decision to use a road grader to remove the rich ceramic-bearing midden from large areas of the site in order to expose the tops of pit features. These were recognizable as dark stains in the yellow sand that were beneath the midden. Some of these “garbage pits” were up to 7 feet across and as much as 4.5 feet deep. They included animal bones, potsherds, freshwater mussel shells, stone tools, charcoal, and burned clay daub. Some also contained human remains and dog burials.

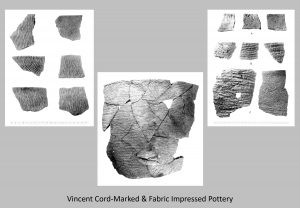

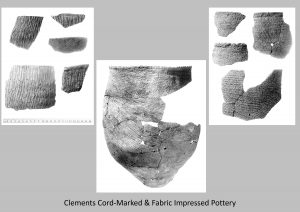

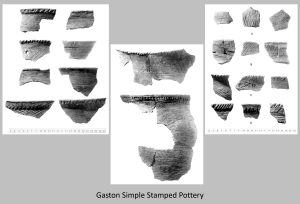

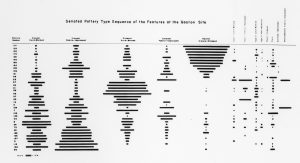

As part of his Master’s thesis at UNC, Stanly South analyzed the ceramics from Gaston in order to establish a site timeline. In the process, he delineated three consecutive occupations: the Vincent phase (Early to Middle Woodland, 1000 BC – AD 300), the Clements phase (Middle to Late Woodland, AD 300-1000), and the Gaston phase (Late Woodland, AD 1000-1600). Pottery making was an invention that corresponds with the beginning of the Woodland period, which is why the Archaic components of Gaston are not included in South’s ceramic seriation.

Along with the ceramic seriation, the features that were uncovered by mechanical stripping provided a lot of information about Native life. As mentioned above, some of the Late Woodland pits contained human or dog burials. Most of the human burials were tightly flexed and placed in simple oval pits. While only one burial had an associated artifact with it (an engraved stone pipe made from chlorite), most of the dog burials contained offerings of deer bone. Unfortunately, many of the features with faunal remains did not have ceramic material, so their dating remains uncertain. The faunal remains from Gaston were analyzed by Amber VanDerwarker as part of a project for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Due to the time constraints involved with the reservoir flooding, all remains from Gaston were sifted through 3/8” screen. This means that many smaller fragments and bones would have gone through the screen, biasing the assemblage towards larger animals. With that in mind, VanDerwarker found that deer was the most abundant animal represented, followed by a number of other mammals including rabbit, squirrel, beaver, muskrat, gray fox, black bear, raccoon, and striped skunk. Canada goose and turkey were also identified, along with a number of turtles and wide range of fish.

Close Woodland

Sources

VanDerwarker, Amber M.

2001 • An Archaeological Study of Late Woodland Fauna in the Roanoke River Basin. North Carolina Archaeology 50:1-46.

Ward, Trawick H., and R. P. Stephen Davis, Jr.

1998 • Time Before History: The Archaeology of North Carolina. University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Whyte, Thomas R.

2008 • Reanalysis of Ichthyofaunal Specimens from Prehistoric Sites on the Roanoke River in North Carolina and Virginia. North Carolina Archaeology 57:97-107.