Stone Drains

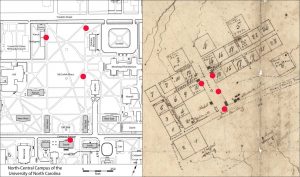

Archaeological excavations and construction-related activities near the heart of the old campus have revealed several drains dating to the mid-nineteenth century. Their ubiquity across the oldest part of campus provides a glimpse of early infrastructure needs and the importance of improving sanitation for the university’s occupants. Constructed of stone, these subterranean stone structures served as early sewers to remove waste and also were used to remove storm water from around building foundations and moisture from basements. Drains have been documented archaeologically along the north side of South Building, between the north end of Old East and Franklin Street, adjacent to and at the northwest corner of the Eagle Hotel, and in front of Vance Hall.

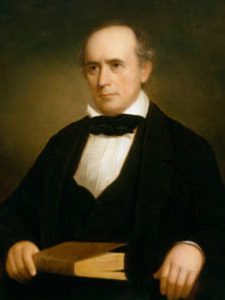

The implementation of campus drainage projects was likely overseen by the celebrated Professor Elisha Mitchell, who came to Chapel Hill in 1818 to teach mathematics. Mitchell, who was “conspicuous” for thoroughness and efficiency, also served as Bursar and Supervisor of the Campus and University Grounds. His most celebrated project as the University’s amateur landscape architect was the low stone rubble walls that are now emblematic of the campus and Chapel Hill generally. Like most construction projects on the antebellum campus, these were executed with slave labor, sometimes that of Mitchell’s own slaves.

South Building

A letter from Mitchell to President Swain (above) in 1844 provides compelling evidence that Mitchell was involved in the design and orientation of the drains themselves. Once again South Building was experiencing drainage problems, and Mitchell, not agreeing with the proposed solution, devised his own plan that he presented to Swain complete with illustrations.

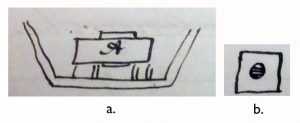

“Mr. Polly desired me to consult you about the arrangements for conveying off the water from the south building. When I stated to him the objections to his plan of pipes running through the building he said it would not answer. And when I stated farther what my own plan was, he said that his assistant had suggested that as the best that could be adopted. The pipes will not remove the water thrown out by the occupants of the rooms from their windows and that is what makes the puddles in which the hogs wallow and make a stink. I propose a blind ditch which the college hands could dig in a week 6 feet deep at a distance of perhaps 15 feet from the front of the building the bottom to be filled with small loose rock to the height of perhaps 3 feet, and then covered over so as to make all smooth. Smaller ditches made in the same way would run up to where the water might be expected to collect and there have their mouths covered with a cut stone and small grating. It could not but keep everything neat and dry _ nor could the cost be much.” (Letter from Mitchell to Swain, 30 December 1844, University Archives)

In 1992, construction crews exposed part of Elisha Mitchell’s stone drain beneath the brick walkway in front of South Building while excavating a trench to install new utility lines. Stone rubble from the drain was exposed at the base of the construction trench and was quickly mapped and documented by UNC archaeologists Vin Steponaitis and Trawick Ward before the excavation was filled in.

McCorkle Place

Two documents in the University Archives associate Mitchell with the placement and design of stone drain systems on campus. One line item in Mitchell’s Bursar Report from October 1842 reads “Charges for lining ditches in grove with stone, $13.00” (19 October 1842, University of North Carolina Papers (#40005), University Archives). The word “grove” was used to refer to the early nineteenth-century campus area known today as McCorkle Place, a wooded quadrangle that extends from the Old Well to Franklin Street. McCorkle Place also is depicted on early maps as part of the “Grand Avenue,” an open corridor that originally extended northwestward beyond Franklin and Rosemary streets.

One of these “ditches” lined with stone was discovered in 2006 by university grounds personnel who were repairing a damaged irrigation line in front of Alumni Hall. A small excavation by UNC archaeologists revealed an intact section of the well-constructed stone drain (view a 3D model below). It was made by digging a ditch approximately 3.5 feet wide and 4.5–5.0 feet deep, placing flat stones across the floor, building foot-wide stone walls on each side, and capping the construction with large flat stones to form a continuous vault measuring approximately 1.5 feet wide and 1.5 feet tall. Probing of the soil both north (toward Franklin Street) and south (toward Old East) of the exposure indicates that the drain likely extended the entire length of McCorkle Place.

Graham Memorial Site

The most extensive archaeological examination of stone drainage features on campus took place during excavations in 1994 of the Tavern House/Eagle Hotel foundations at the Graham Memorial site. Two stone-lined drains were documented there. One ran parallel to the west wall of the hotel while the other ran at an oblique angle from the northwest corner of the basement toward Franklin Street. The section of the drain that ran parallel to the hotel contained numerous fragments of broken dishes manufactured during the second quarter of the nineteenth century as well as broken glassware.

The photographs at right give three views of the drain along the west hotel wall, showing: its relationship to the modern brick walkway along the east side of McCorkle Place and the hotel’s stone foundation on the other side (left); the drain before its capstones were removed (center); and the drain after removing the capstones (right).

The excavations in the cellar beneath the tavern/hotel revealed that drainage had been a persistent problem. On two separate occasions sand was brought in to raise the height of the floor. When this did not solve the drainage problem, a ditch was dug diagonally across the sand floor of the basement to the northwest corner of the foundation, where it fed into a stone-lined drain that directed the water downhill to Franklin Street.

Vance Site

Another stone drain (view a 3D model below) was revealed in 2011 during archaeological excavations on the west side of McCorkle Place in front of Vance Hall. As with the Eagle Hotel drains, this stone drain at the time of its construction in the 1840s was on privately-owned property. However, it extends eastward onto University property and presumably connected with an as-yet undocumented drain along the west wide of McCorkle Place, similar to the one uncovered in front of Alumni Hall. Its size and method of construction also are very similar to that drain.

The photographs at right show the stone drain at the Vance site before removing cap stones and excavating fill deposits, and after all fill has been removed. The capstones are still in place at the east edge of the excavation where the drain extends beneath the modern brick walkway and into McCorkle Place. A modern, white plastic drain pipe crosses the nineteenth-century stone drain.

3D Models of Excavations

Excavation revealing the McCorkle Place drain in front of Alumni Hall

Excavation revealing the stone drain at the Vance site

Contributor

R. P. Stephen Davis, Jr. (Research Laboratories of Archaeology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill)

*Images courtesy of the Research Laboratories of Archaeology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

**Images courtesy of the North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Sources

Davis, R. P. Stephen, Jr.

2015 • The Hidden Campus: Archaeological Glimpses of UNC in the Nineteenth Century. Gladys Hall Coates University History Lecture, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, April 14, 2015.

Davis, R. P. Stephen, Jr., Patricia M. Samford, and Elizabeth A. Jones

2010 • The Eagle and the Poor House: Archaeological Investigations on the University of North Carolina Campus. In Beneath the Ivory Tower: The Archaeology of Academia, edited by Russell Skowronek and Kenneth Lewis, pp. 141-163. University Press of Florida.

Fitts, Mary Elizabeth, Ashley Peles, and R. P. Stephen Davis, Jr.

2012 • Archaeological Investigations at the Vance Site on the University of North Carolina Campus, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Research Report No. 34. Research Laboratories of Archaeology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.