The Second President’s House

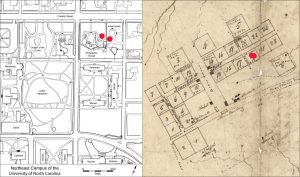

Two archaeological sites have been investigated that contain evidence of what was commonly known at UNC as the Second President’s House, an early nineteenth-century residence built by UNC President Joseph Caldwell just east of campus on the south side of East Franklin Street. After it burned in 1886 the remaining lot, by then owned by the UNC Trustees, was divided and James Lee Love built a new residence on the eastern portion. Archaeological excavations behind the Love House revealed the remains of the well house that stood behind Caldwell’s residence. A decade later, a project to replace the driveway of the UNC system president’s house, built on the same lot in the early twentieth century, revealed the remains of the Second President’s House. Prior to repaving, a brief investigation by UNC archaeologists and students mapped the building’s foundations and sampled the contents of the filled-in basement.

President’s Houses

One of UNC’s first buildings, completed in 1795, was a wood-frame house for the president of the University. Until 1913 when it was moved to a neighborhood just west of campus , the house stood on Cameron Avenue at the west edge of the campus where Swain Hall is now located (old Chapel Hill Lot 2). While intended as the president’s residence, it is most closely associated with Professor Elisha Mitchell who lived there from 1818 until his untimely death in 1857. The University’s first president, Joseph Caldwell, occupied the house from 1796 until 1812, when he resigned his position, and afterward his successor, President Robert Chapman, lived there.

Joseph Caldwell was reappointed president of the University in 1816 and held the position until his death in 1835; however, he chose to remain in a house he had built in 1811 on Lot 19, along Franklin Street northeast of campus. This house became known as the Second President’s House. Caldwell’s wife, Helen Hogg Hooper Caldwell, continued to live in the house until her death in 1846, and from 1849 to 1868 it was the residence of President David Lowry Swain, Caldwell’s successor.

The Second President’s House was the scene of two memorable events—one celebrated and the other scandalized—in Chapel Hill and University history. The first was a large dinner on the front lawn honoring U.S. President James Buchanan, who attended the 1859 commencement; the second was the successful courtship in 1865 of President Swain’s daughter, Eleanor, by the commander of the occupying Union Army, General Smith B. Atkins. After Swain’s tenure, the house was occupied by several other prominent individuals associated with the University until Christmas morning 1886 when it caught fire and burned. Its last resident was the unfortunate Professor Thomas Hume, who had moved into the house just a day earlier.

In 1887, the University trustees agreed to lease the eastern third of Lot 19 to Professor James Lee Love, who built his residence there. This building, with an addition to the back o the house that was constructed in 2004, is now home to UNC’s Center for the Study of the American South). The rest of the lot stood vacant until 1907 when the current UNC President’s House was built. The 1991 aerial photograph at right shows the original extent of Lot 19. Structures associated with President Caldwell’s occupancy are: (a) the Second President’s House; (b) the well house; and (c) the site of a sundial and two pillars to delineate a true north-south meridian line. Current buildings on the property include: (d) the UNC system president’s house; (e) the James Lee Love House, home to the Center for the Study of the American South; and (f) the Hickerson House.

The Well House Excavation

The first archaeological investigations associated with the Second President’s House were undertaken in 2004. The purpose of this work was to evaluate a planned addition to the back of the James Lee Love House for the UNC Center for the Study of the American South. While the excavation recovered numerous artifacts and a few archaeological features attributable to the period when the Love House was occupied, two more significant and unanticipated find were made.

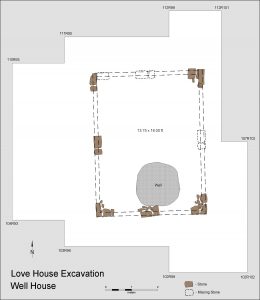

The first of these was the discovery of undisturbed evidence for a 1500-year-old American Indian occupation at the site, represented by a concentration of chipped-stone spear points and broken cooking pot fragments with cordmarked and fabric-impressed exterior surfaces. The ancient remains were contained within an old humus layer beneath the floor where an early nineteenth-century well house once stood. The well house was a wood frame structure that measured about 14 ft by 18 ft and stood on eight stone piers, two of which had been previously removed by a utility line trench. A large well about 5 ft in diameter was located at the south edge of the structure. The upper four feet of fill contained brick rubble, pottery fragments, and other discarded items likely deposited there after fire destroyed the Second President’s House. Below this deposit was sterile fill dirt that extended to an unknown depth. Elsewhere within the area excavated, brick rubble and other debris from the 1886 fire and subsequent clean-up also were revealed.

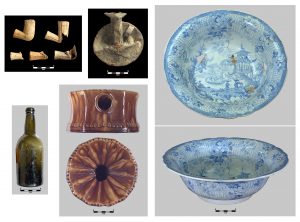

Several thousand artifacts were found that can be associated with the various occupations of the Second President’s House. The artifacts from the well, shown at right, mostly date to the period after the Civil War and many, if not most, of these likely belonged to Thomas Hume when the Second President’s House burned. They include: several locally made clay smoking pipes (top left); a brass candleholder (top center); a green glass beer bottle (bottom left); a ceramic spittoon or cuspidor (bottom center); and a large, reconstructed, blue transfer-printed wash basin (right). Other artifacts, such as small fragments of ceramics that can be dated to the early nineteenth-century, probably date to the period of Caldwell’s occupancy, and a few can be associated with the period when Swain resided here. One particularly intriguing artifact from the Swain era was a U.S. Army officer’s button of a type that dates to the Civil War.

The Second President’s House Excavations

A second archaeological investigation occurred in August 2014, after construction activity to replace the driveway at the current UNC President’s House exposed the stone foundations and filled-in basement of the Second President’s House. Over a brief period of 10 days, UNC archaeologists, students, and volunteers rushed to document and evaluate those remains before they were paved over again. This investigation achieved two goals. First, the tops of the building’s stone foundations for the walls and brick foundations for the end chimneys were cleaned, photographed, and mapped. This provided important information about the building’s dimensions and exact location–pieces of information lacking in written documents. Second, an exploratory trench was dug into the basement, providing information about its depth, overall extent, and the nature of the debris contained within it. The basement had been filled in mostly with brick rubble from the chimneys that stood at each end of the house.

Artifacts were recovered mostly from the excavation into the basement and while cleaning around the foundation stones. A door lock (view a 3D model below) and iron hinges were recovered from the brick rubble fill within the basement trench, and they likely came from the front door. At the top of the basement fill just north of the excavation trench, archaeologists recovered most all of the pieces of a cast iron parlor stove. The stove model was patented by Henry Stanley of West Poultney, Vermont, in 1845, so it likely was installed at about the time President Swain moved into the house. The photographs at right show a catalog picture of the Stanley stove and the front panel that was recovered archaeologically.

Astronomy at the Second President’s House

“President Caldwell had always been fond of the Science of Astronomy. It was on this account that, in 1813…he was called on to be the scientific expert on the part of North Carolina in running the South Carolina boundary line. He built on the top of his dwelling a platform, on which he would take the Seniors in squads of three and four, and point out to them the heavenly bodies. He erected in his garden a sun dial, which stood until the invasion of the Federal cavalry. He also built two pillars, still standing, covered with vines, their eastern and western faces accurately showing the true North and south line in his day.” (from History of the University of North Carolina [vol. 1], by Kemp P. Battle, 1907, p. 334)

3D Model of Artifact

Exterior door lock from the excavation inside the Second President’s House basement

Contributor

R. P. Stephen Davis, Jr. (Research Laboratories of Archaeology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill)

*from Old Days in Chapel Hill, by Hope Summerell Chamberlain, 1926.

**Caldwell portrait courtesy of the Carolina Digital Library and Archives; Swain portrait courtesy of the Dialectic and Philanthropic Societies Foundation; and Hume portrait from Biographical history of North Carolina from colonial times to the present, volume 4, by Samuel A’Court Ashe, 1906.

***Images courtesy of the Research Laboratories of Archaeology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Sources

Boudreaux, Edmond A., R. P. Stephen Davis, Jr., and Brett H. Riggs

2004 • Archaeological Investigations at the James Lee Love House on the University of North Carolina Campus, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Research Report No. 23, Research Laboratories of Archaeology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Davis, R. P. Stephen, Jr.

2015 • The Hidden Campus: Archaeological Glimpses of UNC in the Nineteenth Century. Gladys Hall Coates University History Lecture, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, April 14, 2015.